Even I can see the flags, the stunted and dead leaves, the ailing branches, the signs. I stand outside with the tree, in a state of helplessness — there should be a word specifically for the feeling one has about the death of a tree. I think of photographing Old Stalwart, but I can’t bear to. Within days, the city tree crew arrives and saws off those long sweet limbs, lest the disease spread. I’m so sad I cannot look at the tree anymore, it hurts to see it maimed like that. A few more days pass and then the forester seals off the street, notches the rest of the tree, and fells the three-story-high stump onto the asphalt. I watch it go, with Kiizhikok, and feel the shock of its passage, a resounding shudder of the earth that tingles in our feet. That’s it. It is gone. This has been a warm winter and a record number of elms have succumbed, as the deep cold helps kill off the beetles that spread the sickness. As I am finishing this book, the city stump grinder arrives and by the end of the day his rotary blade has turned the rest of Old Stalwart into a pile of chips. It will be another hundred years, if the house survives this long, before a tree grown in its place tops the roofline and teases the sky.

Reading Distance

My happiness in being an older mother surprises me — though often worn out I don’t seem to mind my sleepy days. I know they quickly pass. Some changes are permanent, though, for instance my middle-aged vision. The first time I held Kiizhikok in my arms, just after she was born, I looked into her perfect face and realized that I couldn’t make out her features. I had to adjust her to my reading distance.

It occurs to me, now, that I now do this constantly. If reading is taken to mean comprehending, I step back often. I focus; to my great relief, I have a little more patience. I have learned to appreciate as well as to fear the swift current of hours. Those first jagged months of ceaseless exhaustion passed like dreams, so quickly I feel I’ve flown in and out of clouds. Already she is making sense of things and I am making sense of her. At the same time, my oldest daughters are soon leaving for college. All this year I have found myself sorting through photographs as though to persuade myself that their childhoods have actually happened, that all of those years really occurred in fabulous particularity.

Returning home, after a long anticipated trip, always does this to me. Time seems foreshortened, furiously spent, a blur. If, as Austerlitz says, time is by far the most artificial of all our inventions, then what am I living in, what is this force that holds me captive in its ineluctable continuance? As I still have Austerlitz to finish on my first night home, the book becomes a reassuring messenger from the near past, familiar now, a witness to my travels.

Austerlitz doesn’t wear a watch, I am happy to read, considering one “a thoroughly mendacious object.” I don’t wear a watch either, unless forced by circumstance. He explains what I have never completely thought out about my hope of somehow resisting time through these little forms of protest. Austerlitz hopes, he says, that time will not pass away, has not passed away, that he can turn back and go behind it and there find everything as it once was. I suppose that is the point of sifting through my shoeboxes of photographs. Perhaps that is the point of everything, this writing most of all.

There is a surprise memory for me at the end of Austerlitz , one that simultaneously revives a forgotten person, a teacher of mine, and gives me an unexpected metaphor to use in understanding where we have been. The last pages of the book are about another book, a memoir by Dan Jacobson, a writer whose father, a Lithuanian rabbi, died in 1920 and caused his wife to decide to emigrate with her nine children to South Africa. They were the only people in his family who survived the Holocaust. Jacobson spent most of his childhood in the town of Kimberly, near the diamond mines, which were not fenced off and to the edge of which children ventured to look down into a depth of several thousand feet. As Dan Jacobson was my advisor during what seemed a very long term of study at University College, London, in 1976, I can almost see him describe how it was terrifying to see such emptiness open up a foot away from firm ground, to realize that there was no transition, only this dividing line, with ordinary life on one side and its unimaginable opposite on the other. The chasm into which no ray of light could penetrate, writes the narrator of Austerlitz , was Jacobson’s image of the vanished past of his family and his people which, as he knows, can never be brought up from those depths again.

Dan Jacobson was a very kind man. I remember that as we talked, perhaps to set me at ease, for I was shy, he used to share chunks of the Cadbury bars he kept in his desk drawer — the kind in the purple wrapper, studded with chunks of nuts and raisins. How odd it seems now that he is with me in Minneapolis, and that I am nodding as I think, yes, it is as though when I look past a generation or into the past of Tobasonakwut’s world there is a lightlessness, too, for nine of every ten native people perished of European diseases, leaving only diminished and weakened people to encounter what came next — the aggressions of civilization including government policies and missionaries and residential schools. Yet, here, as I turn to Kiizhikok sprawled in sleep beside me, is a light.

Wood Ticks

A pure little light, I think, reaching over to touch her curls. That is when I find the wood tick. It is still on the move, not attached, which is good. I pluck it away and dispose of it and make certain there are no more. This one was probably carried in on a shirt or blanket. Suddenly, of course, I itch all over. I don’t know why they are so much worse than mosquitoes, for instance, but they are worse. Or maybe I just have a thing about them. Back on the island while eating lunch with Tobasonakwut, I plucked one off and made a shuddering noise. He opened the top layer of his sandwich and said, “throw him in.” When I was a child and visited my grandparents in the Turtle Mountains, we cousins had wood-tick contests at the end of the day, after playing in the woods. Any number under twenty was scorned. I remember one cousin winning one night with a grand total of fifty-six. In the full blush of their season I’ve seen them swarm toward you off willow branches — swarm slowly. That’s what’s so awful. Their tiny, blood-drawn, implacable lust.

Up close, they are so small and neatly made. Of course, their true awfulness becomes apparent when they vampirize and grow big. Earlier this summer, about a week after bringing our dog back from a trip up north, Kiizhikok brought me a huge tick she’d found, fallen off the dog. She held it solemnly, pinched carefully between her thumb and first finger, her pinky crooked. Its legs, fine as copper hairs, waved hopelessly. I couldn’t breathe for the horror of it — the thing looked like a grape.

Later on I described the moment to Pallas, who was dismissive. “Oh mom,” she said, “Kiizhikok’s much too intelligent to eat anything with legs that move.”

Books. Why?

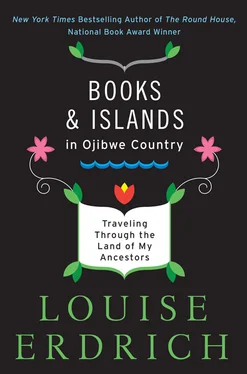

I’ve been to the islands and back. I’ve seen a great many books and held in my hands several that would be set behind glass in the rare books rooms of university libraries. I’ve touched the rock paintings, and read a fragment of their stories. Part of the trip is always the return, the way it shakes off you, the washing of duffel bags of clothes, the tons of catalogs that have collected in the mailbox. The next day, tick free, but sad over the tree and still disoriented, I walk over to our bookstore, Birchbark Books, in Minneapolis. I started it with my daughters for idealistic reasons — the native community, the neighborhood, the chance to work on something worthy with my girls. But really, in my deepest heart, I wonder now if I started it to cure myself of an affliction of books.

Читать дальше