More than 95 percent of Angola’s European inhabitants left in 1975, going to Portugal and other countries, especially Brazil. Some of them are now returning.

Angola’s African population is overwhelmingly Bantu and is divided into more than one hundred tribes, of which the main ones are Ovimbundu, Kimbundu, Bakongo, Lunda, and Nganguela. These five tribes constitute about 80 percent of Angola’s population. The remaining tribes are small, some of them numbering barely several thousand people, others ten thousand or so. More than half of Angola’s inhabitants are followers of various African religions, 35 percent are Catholics, and 13 percent are Protestants. Intertribal conflicts and wars make up a large chapter in this country’s history. They played a significant role in the Angolan war of 1975–76.

There are many reasons for Angola’s low population. For three centuries, a substantial number of inhabitants were enslaved and exported to the other hemisphere. In Angola itself, various forms of slavery survived as late as 1962, in the guise of a system of forced labor. Another cause of the country’s depopulation was the emigration of large numbers of its African inhabitants — around 700,000— mainly to Congo (Zaïre), Namibia, and the Republic of South Africa. Universal malnutrition and the lack of even the most rudimentary health care also contributed to the country’s low demographics.

Angola’s African population was profoundly neglected and abused for centuries. The colonial powers maintained it at the lowest possible nutritional and cultural level. The Angolans constitute one of the poorest societies in Africa. More than 90 percent are illiterate. Only 10 percent of blacks live in cities. Angola is a land of indigent and hungry peasants. A significant portion of these people continue to live in a subsistence economy, an economy of so-called selfsufficiency — or rather, of near-destitution.

Angola’s population is unevenly dispersed. More than half its inhabitants live in an area that constitutes barely nine percent of the country’s territory. Ninety-one percent live on lands that occupy less than half (47 percent) of its terrain.

The main cities, according to the 1970 census, are: Luanda (“the oldest European city in Africa south of the Sahara”— John Gunther), approximately half a million inhabitants; Huambo (62,000); Lobito (60,000); Benguela (41,000); Lubango (32,000); Malanje (32,000); Cabinda (22,000).

It is worth pointing out, since it is not widely known, that Angola is a multiracial society, including many white people, as well as many mulattos of all shades. There are several white ministers in Angola’s government, one frequently encounters white soldiers in the army, and whites constitute a sizeable portion of the inhabitants of cities and villages.

In 1482, the Portuguese captain Diogo Cão arrived at the mouth of the Congo River. At the time, the great African kingdom of Congo flourished here, with its capital at Mbanza known in Portuguese times as São Salvador and today called M’banza Congo. In 1975, São Salvador was a small, provincial town, the capital of the Angolan province of Zaïre, from which hails Holden Roberto and nearly the entire leadership of the FNLA. The year in which Diogo Cão reached the kingdom of Congo can be said to be the start of Portuguese expansion in this part of Africa, although the de facto conquest of Angolan territories began ninety years later, when Paulo Dias de Novais established a settlement named Luanda in 1573 and set off with a group of soldiers down the Cuanza River.

Ten years after Diogo Cão set foot upon the Congo-Angolan land, Christopher Columbus reached the shores of the American continent. The two events are closely related. European emigrants in America begin to establish plantations of sugar cane and cotton: demand develops for a large and cheap labor force, because the cultivation of sugar especially requires a huge number of hands. The slave trade starts. The history of sugar and the history of slavery are part of the same chapter in the history of the world. Africa becomes the principal supplier of slaves — and especially Angola. According to historians, 3–4 million slaves were shipped out from the territories that lie within the borders of present-day Angola. This number might not appear so shocking today, but one must consider it in the light of contemporary population figures. In the days when Portugal was a world power and had large possessions on several continents, it boasted barely one million inhabitants. For nearly four hundred years, slavery is the cornerstone of Angolan history. As late as the first half of the nineteenth century, the export of slaves constitutes more than 90 percent of the overall value of Angola’s exports. A significant portion of the population of today’s Brazil, Dominican Republic, and Cuba are the descendants of Angolan slaves. It is also no coincidence that despite fundamental political differences, the first state to recognize the People’s Republic of Angola was Brazil, and that Cuba gave the greatest assistance to the Angolan liberation forces.

To understand our world, we must use a revolving globe and look at the earth from various vantage points. If we do so, we will see that the Atlantic is but a bridge linking the colorful, tropical Afro — Latin American world, whose strong ethnic and cultural bonds have been preserved to this day. For a Cuban who arrives in Angola, neither the climate, nor the landscape, nor the food are strange. For a Brazilian, even the language is the same.

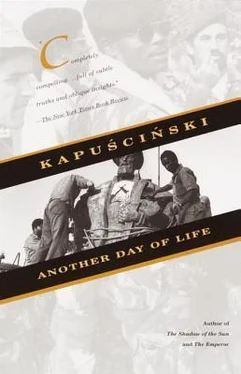

The export of slaves was the main reason for the Portuguese presence in Angola. To round up as many of them as possible, the Portuguese conducted ceaseless wars here. “The Portuguese contact with Angola,” write the historians Douglas L. Wheeler and René Pelissier in their book Angola , “began with war and, as some believe, will end with war.

The Portuguese politics of penetrating Angola began with a military expedition which was to be the start of a series of wars lasting for centuries. The state of war did not abate by the end of the seventeenth century; to the contrary: war was the rule rather than the exception during the entire period between 1579 and 1921. Unpublished documents in Portuguese archives prove that in the course of 350 years there were barely five during which the Portuguese did not conduct war in one place or another in Angola.”

This rapacious theft of human beings brought Angola to such ruin that at the beginning of the twentieth century England and Germany actually conducted secret negotiations to take the colony from Portugal and divide it between themselves. In any case, the Germans occupied southern Angola until 1915, and the Afrikaners (the so-called Boers) occupied the southern province of Huíla (with its capital of Lubango) until 1928.

For several centuries Portugal directed its best elements to Brazil, its worst to Angola. Angola was a penal colony, the place of deportation for all manner of criminals and outcasts, for all those on society’s fringe. In old Lisbon, Angola was referred to as the país dos degredados , the country of the deported, the expelled, the finished. The low quality of Angola’s colonists helped Angola become one of the most backward of African countries.

The struggle for the liberation of Angola begins on a significant scale only in the middle of the twentieth century. Here are a few of the more important dates:

1948

The creation of the cultural movement “Vamos descobrir Angola” (Let us discover Angola). It is the brainchild of a group of young Angolan intellectuals. They publish two issues of the literary periodical Mensagem (“The Message”), subsequently closed down by the police. Its editor, and the leader of the movement, was the eminent Angolan poet Viriato da Cruz. His closest associates were two other poets, Agostinho Neto and Mario de Andrade. The rise of the Angolan liberation movement is attributable to these three poets.

Читать дальше