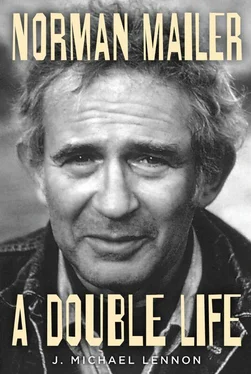

Norman Mailer

A Double Life

by

J. Michael Lennon

To my wife, Donna Pedro Lennon, and Barbara Mailer Wasserman, with love and gratitude

and to the memory of Robert F. Lucid

“There are two sides to me, and the side that is the observer is paramount.”

— Norman Mailer

PROLOGUE

The Riptides of Fame: June 1948

After delivering the manuscript of his war novel The Naked and the Dead to his publisher, Norman Mailer sailed to Europe with his wife, Beatrice, on October 3, 1947. Having for most of his life known only the Depression and the war in the Pacific, he had always viewed with romantic envy the expatriate pasts of the Lost Generation writers he admired: Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Dos Passos, and Henry Miller. So to go to Europe on the GI Bill as he now could seemed like a miraculous opportunity. Paris was the bull’s-eye destination for aspiring writers, including Stanley Karnow, a Harvard graduate and veteran who arrived there a few months before Mailer. His memoir, Paris in the Fifties , opens with the question: “ Porquoi Paris? Its name alone was magic. The city, the legendary Ville Lumière , promised something for everyone — beauty, sophistication, culture, cuisine, sex, escape and that indefinable called ambience.” Mailer partook of all of these pleasures during his ten-month stay there. He differed from most of his countrymen, however, in one respect: he was a writer when he arrived: besides Naked , he had written two unpublished novels in college. While enjoying Paris and taking trips to other countries, he was trying to get a new novel going. It was one of the happiest seasons of his life, shadowed only by his anxiety about the future.

In the spring of 1948 he drove to Italy in a small Peugeot, accompanied by his wife, younger sister, and mother — Beatrice, Barbara, and Fanny. They left Paris on June 1, drove east to Switzerland and then south to Italy. It began to rain as they drove through the foothills of the Alps, and turned to snow when they reached higher elevations. Mailer had to keep downshifting on the hairpin turns because the Peugeot didn’t have much horsepower. By the time they reached the St. Gotthard Pass, they were in a blizzard. At the peak they had to back up to let another car pass, coming perilously close to the edge. Mailer relished the experience. They spent a few days in the villages and resorts of the northern lake country, and then moved on to Florence and Venice. In mid-June they arrived in Rome, where they hoped to pick up their mail, forwarded by Mailer’s father, Barney, an accountant working for a postwar relief organization in Paris.

Rinehart and Co., Mailer’s publisher, had mounted a major publicity campaign for The Naked and the Dead , and he and his family (his mother and sister had come over in April) were eager for news of its reception. The mail in Rome contained several reviews, all positive, even glowing. After two or three days of sightseeing, Fan left them and took the train back to Paris to join Barney. Mailer, Bea, and Barbara drove down to Naples, then on the morning of June 23 they began the long drive back to France. Mailer was preoccupied, thinking about the reviews, the return trip to the United States, and a cable he had just received from Lillian Hellman, who wanted to write a dramatic adaptation of his novel. He had seen her play The Little Foxes on Broadway when he was in college, and had “a lot of respect for her as a playwright,” as he told his editor. In Paris, he had begun a new novel, but it was a fragment, and he didn’t know if he wanted to continue with it. He had the feeling that he’d be busy when he got home in August. They drove on, and after a long ride arrived in the late afternoon at the American Express office in Nice. Barney had forwarded the next batch of mail from the States.

A month earlier, Mailer recorded his anticipations in his journal. He had seen “batches of reviews” by May 12—the novel came out on May 6—and realized its prospects were excellent.

The thing I’ve got to get down here is my reactions to the book’s success. The depression to start with — I feel trapped. My anonymity is lost, and the book I wrote to avoid having to expose my mediocre talents in harsher market places has ended in this psychological sense by betraying me; I dread the return to America where every word I say will have too much importance, too much misinterpretation. And of course I am sensitive to the hatreds my name is going to evoke.

But across from that is the other phenomenon. I feel myself more empty than I ever have, and to fill the vacuum, to prime the motor, I need praise. Each good review gives fuel, each warm letter, but as time goes by I need more and more for less and less effect. This kind of praise-opium could best be treated in fiction through the publicity mad actress who has to see her face and name more and more to believe in her reality, and of course loses the line between her own personality, and the one created for her by the papers.

Mailer’s desire for fame, and his distaste for it, never abated over his long career. Nor did his ability to determine how he might write about his current situation, whatever it might be. It became a reflex.

Hot and dusty and sweaty from the ride to Nice, Barbara and Bea sat in the Peugeot while Mailer went in for the mail. He returned with an enormous packet of clippings, cables, reviews, and letters. “The reviews were mostly marvelous,” Barbara wrote. “Our friends were all excited and writing to us (I remember my Progressive Party lover wrote, ‘What kind of book is this that both the Times and the Daily Worker praise?’)” The atmosphere in the car got “somewhat frenetic and hysterical.”

I don’t think we finished reading any letter or review because it was always interrupted by word of a comment on what someone else was reading. Finally Norman said, in a rather small voice which I will never forget the sound of because it so totally captured the feeling that none of this was quite real, “Gee, I’m first on the best seller list.” We laughed. And laughed. And I thought of all this excitement going on 3,000 miles away, and Norman was the cause of it, but it didn’t seem to have any relation to “Us.”

Looking back on that day almost sixty years later, Mailer said, “It was a great shock.” He had been hoping he would earn enough money from Naked and the Dead to write his next book. Now the novel was number one on the New York Times bestseller list, where it stayed for eleven consecutive weeks. All told, it remained on the list for sixty-two weeks. “I knew I’d be a celebrity when I came back to America and I felt very funny towards it, totally unprepared,” he said. “I’d always seen myself as an observer. And now I knew, realized, that I was going to be an actor. An actor on the American stage, so to speak. I don’t mean I knew it all at once. But there were certainly intimations of that.”

Shortly after leaving the army, Mailer had been told by a New York editor that no one was interested in war novels. Everyone was tired of the war. But by 1948, readers were eager to remember and explore the experience, and Mailer’s novel, which looked at World War II from both the battlefields of the Pacific and the home front, was perfectly suited. “It was the luckiest timing of my career,” he said later. Even so, he was concerned that the publicity surrounding the novel, and its huge sales, would alienate the readers of the leading literary journal in the United States, the Partisan Review. Success as a writer, he said, was like getting “caught in a riptide. Two waves coming in from different directions. You get more attention in one place and less in the other. The ego is on a jumping jack.” He and Bea believed PR ’s readers were mainly snobs, but he still wanted to see his name on its front cover.

Читать дальше