Fan’s deception was common in that era. Barney’s secret compulsion, one he clung to his entire life, was deeply hurtful. His gambling destroyed Fan’s blithe hopes for a carefree life, forced her to become the chief breadwinner, and caused severe tensions with the Kesslers. Mailer said that “the Kesslers felt guilty. They knew that they hadn’t really leveled; they had not warned her off. They were happy to get him married to her.” In retrospect, the only member of his family who was not completely appalled by Barney’s gambling was his son. In 1944, while undergoing basic training, Mailer ended a letter to his father, as follows: “As time goes by, I feel more and more like you, more and more your son. On outward things we are very different, but I think I understand and sympathize with you, better than any person I know.”

He concluded that he was “lucky that my parents are so different, that I have had such a range of personality to draw on.” Shortly after his mother died, he described his parents. “My mother,” he said, was, if you will, the motor in the family, and without her I don’t know what would have happened to us. My mother had an iron heart. My mother was not unlike many other devoted, loving Jewish mothers. She had circles of loyalty. The first loyalty was her children. The second was her sisters, her family. The third loyalty was her husband. The fourth her cousins, the fifth, neighbors she’d known for 20 years. It was a nuclear family. And my mother was the center of it and my father was one of the electrons. I must say he was a most dapper electron. And women adored him because he had the gift of speaking to each woman as if she was the most important woman he’d ever spoken to. And he didn’t fake it. He adored women.

In the early evening of January 30, 1923, Fan felt labor pains and was admitted to Monmouth Memorial Hospital. Dr. Slocum, the Schneider family physician, was summoned. A son was born at 7:04 A.M. on January 31, after Fan had been in labor for twelve hours. It was a difficult, breech birth. The baby’s Hebrew name, Nachum Melech, came from his grandmother Mailer’s brother, Nachum Melech Shapiro, who arrived in the United States in 1900. “Melech” means king in Hebrew, but his birth certificate says “Norman Kingsley Mailer.” Because Barney had not applied for citizenship when he married Fan, their son was legally a British citizen at birth. He chuckled when he learned of this circumstance many years later, joking that it might allow him to become “Sir Norman.” His parents became citizens in 1926.

The Schneiders began to prosper in the hotel business during the boom-year summers of 1920–23. They purchased three large “cottages” on Ocean Avenue. The complex, overlooking the beach, was named “Kingsley Court” in honor of Norman. This success encouraged Fan and Barney to try their hand at what was now a burgeoning family business. Barney was still working in an accounting position in New York, but in 1924 he and Fan rented Kingsley Court from her parents for $4,000 and operated it as a small hotel. They did the same the following summer and made a good profit.

Norman was the darling of the clan, catered to by his parents, grandparents, three aunts, and three older female cousins, Osie, Adele, and Sylvia, plus Dave and Anne Kessler, who visited often. One summer day in 1925 when Norman was two and a half, Adele remembered, he locked himself in the bathroom and called out the third floor window, “Goodbye everybody forever.” Fan went into hysterics and called the fire department, but he let himself out before the firemen came. During the summers of the mid-1920s, he often left home in a huff. Adele said, “He’d get angry; he’d leave a note for his mother, ‘Goodbye forever,’ and he’d walk around the block. His temper would abate and he’d come back.” These tantrums are the first recorded instances of Mailer’s lifelong and pronounced impetuosity, and his impulse to dramatize.

Nearly every year one or another member of the family leased a new hotel, trying to find the right combination of variables for a windfall season. But profits were meager and Fan got discouraged. She became pregnant in the summer of 1926 and by the end of the season was drained. “I had no heart for the hotel business,” she wrote. “It was just devouring all my strength for nothing.” The birth of Barbara Jane on April 6, 1927, increased the load, as did her aging parents, whose health was declining rapidly. The stress of running a busy resort hotel and taking care of her small children made Fan “very, very upset,” according to Barbara. “Her parents were dying, and she realized my father was a gambler; she went to her doctor and told him, ‘I think I’m going to have a nervous breakdown.’ Dr. Slocum said, ‘Fanny, there’s nothing I can do for you. You’re going to have to pull yourself together.’ My mother said, ‘So I pulled myself together.’ ” Fan’s mother died on May 29, 1928, at the age of seventy. Shortly afterward, when Barbara was eighteen months old, and her brother five and a half, the Mailers moved to Brooklyn, while Rabbi Schneider moved in with his son Joe. In late November, the beloved patriarch died of heart disease and was eulogized at the synagogue he had helped to found.

THE MAILERS SETTLED on Cortelyou Road, a few blocks from Flatbush Avenue. Norman, not yet six, began school in September at P.S. 181, a few blocks from their four-room apartment. Barney left early for work in Manhattan and Fan walked Norman the half mile through the lower-middle-class Jewish neighborhood to school, leaving Barbara with a nurse, Agnes. As always, Fan was anxious about the goyim — many second-generation Irish and Italians lived nearby. Mailer completed grades one through four at P.S. 181 and his grades were uniformly excellent. His mother was the leader of a tribe of women who, throughout his childhood, coddled and praised him, catered to his whims and encouraged his individuality. His cousin Adele remembered that for Fan, “it was always Norman.” Barbara quickly recognized this reality but never showed any animosity or jealousy. There were no gaps in the circle of female affection surrounding the young prince.

With the passing of her parents, Fan and Barney began living a different kind of life. They ceased observing Jewish dietary laws. Mailer recalled that his mother was not deeply religious. “She was observant,” he said. “There’s a difference.” Barney, he continued, “was pro-forma observant.” Barbara remembers her mother lighting the candles on the eve of the Sabbath. “I still have the image of Mother, her back to me, lighting the candles that sat on the antique cabinet and whispering a prayer in Hebrew. It was one more element in that adult world which baffled but protected me.” Her brother remembered his mother telling him that the Shekinah, a divine female embodiment of the spiritual, passed over the candles when they were lit. Often, he said, Fan had tears in her eyes.

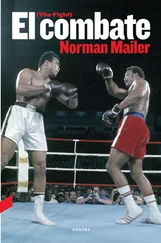

When he was seven or eight, with Fan’s encouragement, he began writing stories. One of the earliest surviving pieces, in six chapters of three to four hundred words each, is “The Adventures of Bob and Paul,” the story of twin brothers who survive perilous adventures. Another notable piece among the early juvenilia is a three-page how-to booklet, “Boxing Lessons.” It consists of a series of tips and observations about Mailer’s favorite sport. “When I land,” it begins, “every ounce of my weight goes into the punch. The timing of it I get by humming a tune and crashing in when I see an opening.” Boxing was a sport that he engaged in and wrote about for several decades, producing what are, arguably, some of the finest boxing narratives written by an American.

The culmination, and the conclusion, of Mailer’s early writing career came early. During the winter of 1933–34, he finished reading the Princess of Mars books of Edgar Rice Burroughs and also became a devoted fan of the Buck Rogers show on the radio. Encouraged by his mother, he wrote a 35,000-word novel, “The Martian Invasion, A Story in Two Parts,” and dedicated it to “My mother, who always wanted me to write a good story.” “This novel filled two and a half paper notebooks,” he recalled. “You know the type, about 7×10. They had shiny blue covers, and they were, oh, only ten cents in those days, or a nickel. They ran to perhaps 100 pages each and I used to write on both sides.” The novel was written in a disciplined spurt during the summer of 1934 at one of the family’s hotels in Long Branch. Mailer’s bottomless fascination with war, violence, and suffering is on display in this adventure novel.

Читать дальше