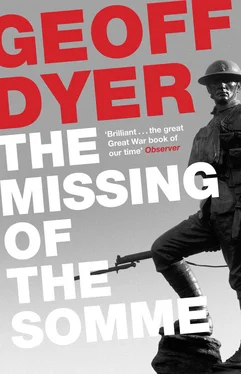

Geoff Dyer - The Missing of the Somme

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Geoff Dyer - The Missing of the Somme» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Canongate Books, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, Критика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Missing of the Somme

- Автор:

- Издательство:Canongate Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Missing of the Somme: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Missing of the Somme»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Missing of the Somme — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Missing of the Somme», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

After meeting him in Craiglockhart in August 1917, Owen began immediately and consciously to absorb the influence of Sassoon. Enclosing a draft of the poem ‘The Dead-Beat’, Owen explained in a letter how, ‘after leaving him, I wrote something in Sassoon’s style’. Sassoon also lent Owen a copy of Under Fire , which he read in December. Sassoon took a quotation from Barbusse’s novel as an epigraph for Counter-Attack and Owen used passages as the basis of images in his poems. ‘The Show’ and ‘Exposure’.

If Owen found it helpful to see his own experience of the war through first Sassoon’s and then Barbusse’s words, it has since become impossible to see the war except through the words of Owen and Sassoon. Literally, since so many books take their titles from one — Remembering We Forget, They Called it Passchendaele, Up the Line to Death — or the other — Out of Battle, The Old Lie, Some Desperate Glory — of them. Owen’s lines in particular offer a virtual index of the themes and tropes featured in these books: mud (‘I too saw God through. .’); gas (‘GAS! Quick, boys!’); ‘Mental Cases’; self-inflicted wounds (‘S.I.W.’); the ‘Disabled’; homoeroticism (‘Red lips are not so red. .’); ‘Futility’. .

So pervasive is his influence that a poem about the Second World War, Vernon Scannell’s ‘Walking Wounded’, seems less an evocation of an actual scene than a verse essay on Owen. Owen’s ‘stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle’ becomes the ‘spandau’s manic jabber’ (the rhythmic similarity enhanced still further by the Owenesque near rhyme of ‘jabber’ and ‘rattle’). The wounded, when they enter, look like they have tramped straight out of ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’:

Straggling the road like convicts loosely chained. .

. . Some limped on sticks;

Others wore rough dressings, splints and slings. .

Scannell was aware of this; as Fussell points out, he even wrote a poem about how ‘whenever war is spoken of’, it is not the one he fought in but the one ‘called Great’ that ‘invades the mind’.

The difficulty for recent novelists is that the same thing also happens when they are dealing with the Great War itself.

Recent novels about the war have the benefit of being more precisely written, more carefully structured than the actual memoirs, which tend, with the magnificent exception of All Quiet on the Western Front , to be carelessly written and structured. Robert Graves’ Goodbye to All That , Richard Aldington’s Death of a Hero , Guy Chapman’s A Passionate Prodigality , Frederic Manning’s The Middle Parts of Fortune (also known as Her Privates We ) and Sassoon’s The Complete Memoirs of George Sherston all contain impressive passages, but none has the imaginative cohesion of purpose and design or the linguistic intensity and subtlety to rival the English translation of Erich Maria Remarque’s masterpiece. 16

The problem with many recent novels about the war is that they almost inevitably bear the imprint of the material from which they are derived, can never conceal the research on which they depend for their historical and imaginative accuracy. Their authenticity is mediated; they feel like secondary texts. In 1959 Charles Carrington complained that certain passages in Leon Wolff’s In Flanders Fields read like ‘a pastiche of the popular war books which everyone was reading twenty-five years ago’. Thirty-five years on, Wolff’s evocative historical study of the Flanders campaign is likely to be a major source book for anyone wishing to fictionalize the war. We have, in other words, entered the stage of second-order pastiche: pastiche of pastiche.

In the Afterword to the 1989 edition of Strange Meeting (the title is, of course, from Owen), her novel about the friendship that develops between two English officers at the front, Susan Hill notes that as well as immersing herself in memoirs and letters, she had, in writing her book, to make ‘an imaginative leap’ and ‘live in the trenches’. Though successful in its own terms, this leap is over-determined by the material amassed in the run-up to it. Especially in the sections of the novel which try to pass themselves off as unmediated primary sources — the letters supposedly written by David Barton, the younger of the two central characters.

Well there [he writes to his mother], I have told you what it’s like and made it sound bad because that is the truth and I would have you believe it all, and tell it to anyone who asks you with a gleam in their eye how the war is going. A mess. That’s all. . Tell all this to anyone who starts talking about honour and glory.

We have noticed a tendency, during the war, to look forward to a time in the future when the participants’ actions could be looked back on; here is the opposite process of historic back-projection. Barton’s letters fail to ring true — not because he would not have expressed sentiments like this, but because, ironically, they correspond so exactly with those established as the historical legacy of the war. Their authenticity derives from exactly the process of temporal mediation they have, as letters , to disclaim. In this instance it is difficult not to recall the famous passage from A Farewell to Arms in which Hemingway established the template for Barton-Hill’s sentiments:

I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious, and sacrifice and the expression in vain. . Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, hallow were obscene.

In a later letter Barton observes, parenthetically, that if British soldiers are attending to the wounded, the Germans ‘often hold their fire. . as we do’. Again, it is the verifiability of the observation that renders its dramatic authenticity suspect. Barton’s remark is the product, we feel, not of the contingency of his own experience but the judiciousness of Hill’s research.

The imaginative fabric of Sebastian Faulks’ impressive war novel Birdsong absorbs the research so thoroughly that only a few of these leaks appear. Faulks’ own observation, that one of his characters ‘seemed unable to say things without suggesting they were quotations from someone else’ nevertheless has ironic relevance to some passages in the book. Just back from leave, an officer gives vent to his loathing of the civilians living comfortably back in England: ‘Those fat pigs have got no idea what lives are led for them,’ he exclaims. ‘I wish a great bombardment would smash down Piccadilly into Whitehall and kill the whole lot of them.’ An entirely authentic sentiment, but one too obviously derived from a famous letter of Owen’s (see p. 29 above) to ring individually true.

Given the near impossibility of remaining beyond the reach of Sassoon and Owen, one solution is to include them in the fictive world of a novel. Pat Barker has done exactly this in two fine novels, Regeneration and The Eye in the Door . Set in Craiglockhart, the former opens with a transcription of Sassoon’s famous declaration and dramatizes many of the crucial moments in his relationships with Dr W. H. R. Rivers and Owen (including his detailed amendments to early versions of ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’).

Unlike Hill, Faulks and Barker, Eric Hiscock actually served in the war and saw action near Ypres in the spring of 1918. Born in 1900, he did not publish his memoir The Bells of Hell Go Ting-a-ling-a-ling until 1976, six years after the first edition of Strange Meeting . The fact that he has no gifts as a writer makes his case more revealing. On one occasion he notes that the

ever-present dreamlike quality of the days and nights (nights when I heard men gasping for breath as death enveloped them in evil-smelling mud-filled shell-holes as they slipped from the duckboards as they struggled towards the front line) filled me with an intense loathing of manmade war.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Missing of the Somme»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Missing of the Somme» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Missing of the Somme» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.