Geoff Dyer - The Missing of the Somme

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Geoff Dyer - The Missing of the Somme» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Canongate Books, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, Критика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Missing of the Somme

- Автор:

- Издательство:Canongate Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Missing of the Somme: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Missing of the Somme»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Missing of the Somme — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Missing of the Somme», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The self-contained ideal of remembrance

Sometimes they are the only old things in the new No Man’s Land of bankrupt businesses and boarded offices, broken lifts and derelict estates. They have been around so long they seem part of the landscape: it is impossible to imagine a time when they were not here. For years now, children who watched the statues being unveiled have been dying of old age. Perhaps what they commemorate, then, is their own survival, the enduring idea of remembrance. The most common form of sculpture — a soldier, head bowed, leaning on his downward-pointed rifle — actually represents the self-contained ideal of remembrance: the soldier being remembered and the soldier remembering. Sculptures like this appeal to — and are about — the act of remembrance itself: a depiction of the ideal form of the emotion which looking at them elicits.

Throughout the 1920s, and especially in the early thirties, attempts were made to ally the rituals of Remembrance with the cause of peace: war memorials, it was argued, should be termed peace memorials; white ‘peace’ poppies were sold by the Peace Pledge Union as an alternative to the red poppies of the British Legion. Already, by 1928, however, the public was beginning to cease thinking of itself as ‘Post-War’ and was beginning, in the words of a contemporary commentator, ‘to feel that it was living in the epoch “preceding the next Great War”’. But this was exactly the period when the Great War was being remembered — in novels and memoirs — most intensely. Again there is a strange temporal elision as the idea of Remembrance merges into a notion of Preparedness. Accordingly, sculptures erected in memory of the First World War come also to look forward to the Second. As war with Germany looms again, the memorial sculptures come to represent a form of symbolic rearming whose job is not simply to protect the past but to guard against possible futures.

On the Croydon memorial P. J. Montford’s figure bandages a wound as if in readiness for further exertions; in Port Sunlight two fit men — sculpted by William Goscombe John — prepare to defend a third who is wounded; John Angel’s figure in Exeter and Walter Marsden’s in St Anne’s on Sea show soldiers weary but ready (if necessary the rifle that was broken in victory in one sculpture will be wielded as a club in this one).

Jagger’s figures lent themselves particularly well to the new conditions in which remembrance merged into resolve. Resisting suggestions that any peace symbolism be included in the Royal Artillery Memorial, he had emphasized that the ‘terrific power’ of the artillery represented the ‘last word in force’. This, he had insisted, was a war memorial.

On the south coast, in Portsmouth, Jagger’s machine-gunners were already in place. As plans were made to entrench ourselves in our island stronghold, the weary Tommies became sculptural equivalents of the Home Guard: men from an earlier war whose effectiveness was largely symbolic. This time it was not gallant Belgium but Britain itself that had to be protected — and these figures became everyday reminders of Britain’s resolve to stand firm. Battered but resilient, they were visible prefigurements of Churchill’s determination to fight invaders at every street corner.

In 1944 the Guards Division Memorial in St James’s Park was badly damaged by a German bomb. The sculptor Gilbert Ledward thought this improved it because ‘it looked as though the monument itself had been in action’. When the Ministry of Works got round to repairing it, Ledward suggested that some ‘honourable scars of war’ be allowed to remain — a way of registering how, in memorializing one war, his monument had participated in another.

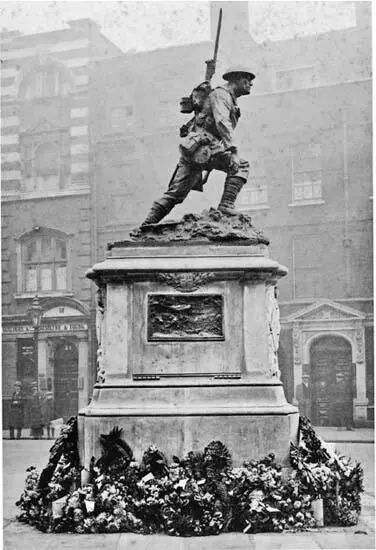

Sculpted by Philip Lindsey Clark, the Southwark War Memorial in Borough High Street shows a soldier striding forward. Soon after it was unveiled, this photograph was taken. Few other images contain so much time.

Time

The statue preserves or freezes a moment from the war. This record itself ages, very slowly. Since it was taken, both the statue and the photograph itself have aged. Looking at it now, what we see is an old photograph of a new statue. In the background, gazing at the camera, are four men and a boy. The long exposure time has caused these figures — who moved slightly — to ghost, especially the two on the right whom we can see right through. Any figures walking past will have vanished completely. Because it is utterly still, the statue itself is substantial and perfectly defined — all the more strikingly so given that it shows an infantryman moving purposefully forward. The photograph is therefore a record of time passing : both in relation to the statue (which, relative to the people looking at it, is fixed in time) and through it (because the statue itself no longer looks quite as it does in the photograph). Compared with the solid permanence of the memorial, even the buildings in the background seem liable to fade. What we see, then, is the sculpture’s own progress through time; or, more accurately, time as experienced by the sculpture. Simultaneously, the old time of the onlookers, this moment of vanishing time, is preserved in the picture which records its passing.

In a few days we will be leaving for Flanders. Mark tells me he has been reading Trevor Wilson’s huge history, The Myriad Faces of War , as preparation. I am impressed and a little shamed by his diligence. My own reading of general histories of the war is characterized by a headlong impatience. Basil Liddell Hart, A. J. P. Taylor, John Terraine, Keith Robbins — I read them all in the same inadequate way. With a cloudless conscience I skim the same parts of each: the war at sea, air raids on London, anything happening on the Eastern Front, Gallipoli. . Then there are the parts of these histories I try hard to concentrate on but whose details I can never absorb : the network of treaties, the flurry of telegrams and diplomatic manoeuvres that lead up to the actual outbreak of war. Consequently everything between the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand and the lamps going out over Europe is a blur.

Although I always dwell on the period of enthusiastic enlistment, I move attentively but fairly quickly through the period 1914–15. It is not until the great battles of attrition that I am content to move at the pace of the slowest narrative. From the German offensive of 1918 onwards I am once again impatient and it is not until November, the armistice and its aftermath, that the speed of history and my reading of it are again in equilibrium.

For me, in other words, the Great War means the Western Front: France and Flanders, from the Somme to Passchendaele. Essentially, then, mine is still a schoolboy’s fascination. Uncertain of dates and eager for battles, I pause again over a passage I had marked years before, when I was a schoolboy, in Leon Wolff’s In Flanders Fields :

. . a khaki-clad leg, three heads in a row, the rest of the bodies submerged, giving one the idea that they had used their last ounce of strength to keep their heads above the rising water. In another miniature pond, a hand still gripping a rifle is all that is visible, while its next door neighbour is occupied by a steel helmet and half a head, the staring eyes glaring icily at the green slime which floats on the surface at almost their level.

All of which is of no interest except in so far as my own interests coincide with the remembered essence of the conflict. Is it not appropriate and inevitable that I should move quickly through the period of the war’s relative mobility before getting stuck into every detail of the stalemate of 1916–17? Rather than being a quirk of temperament, perhaps this is how the war insists on being remembered, on remembering itself . .

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Missing of the Somme»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Missing of the Somme» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Missing of the Somme» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.