A work from slightly earlier, Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s haunting The Fallen of 1915–16, shows that sculptural language beginning to express itself in terrible sobs. A naked, painfully etiolated figure is on his hands and knees. His head hangs to the floor. The grief of Europe seems to bear down on his back but this fallen youth is still supporting himself, resisting the last increment of collapse (his head touches the floor but this sign of helplessness adds to the sculpture’s structural stability). Another work by Lehmbruck, Head of a Thinker , shows a figure whose arms appear to have been wrenched off, leaving the shoulders as rough stumps; the left hand is clenched against the chest from which it protrudes. Lehmbruck worked as an orderly in a military hospital in Berlin and was devastated by the injuries and suffering he witnessed. He committed suicide in 1919, but his work might have provided a model for future memorials.

Similar works — better ones, sculptures stripped of Lehmbruck’s tendency to implicitly elide the suffering of the artist with that of the fallen soldier — could have forced themselves into existence in the inter-war years in Britain. Alternatively, given that the figurative sculptural tradition is inherently heroic, the possibility existed for a realist sculpture which showed the suffering of war more nakedly than ever before: a group of men advancing and falling in the face of machine-gun fire, stretcherbearers floundering in mud. . Sculptures do show injured soldiers but the wounds tend to be heavily formalized, hindering rather than maiming. The sculptural representation of slaughter exists only in a bas-relief by Jagger. Now in the Imperial War Museum, No Man’s Land of 1919–20 shows a sprawling wilderness of men dying and wounded, one of whom hangs crucified from barbed wire.

That such an explicit depiction of battle was nowhere given fully three-dimensional expression highlights another absence — especially if the bas-relief as a form is considered as the bronze or stone equivalent of a photograph, as a static tracking shot. While they could convey the aftermath of action, it was physically impossible for photographers to capture battle itself (one of the reasons the sequence of soldiers going over the top at the Somme is obviously faked is precisely because it was filmed); as a medium sculpture was capable of rendering the unphotographable experience of battle. Although many had the talent, no British sculptor — not even Jagger — had the vision, freedom or power to render the war in bronze or stone as Owen had done in words.

This speculative account of sculptures that were not made is really only an attempt to articulate a sense of what is missing from those that were : a way of describing them in terms not of stone or bronze but of the time and space which envelop and define them. What is lacking is the sense of a search for a new form, a groping towards new meaning rather than a passive reliance on the accumulated craft of the past. 15

Even taking this absence into account, the realist memorials represent a great flowering of British public sculpture. That they may not have been the work of exceptional individual talents illustrates how, at certain moments in the tradition of any art, the expressive potential of the average can exceed that of the outstanding at earlier or later dates. Nowadays the human form cannot so readily be coaxed into such powerful attitudes; only an exceptional artist today could achieve the power routinely managed by the memorial sculptors, almost all of whom, except Jagger, have been forgotten.

We drive through Keighley on our way to watch Leeds — Everton at Elland Road. Clouds hug the ground. The anorak, a foreigner would suppose, is the English national dress. The most frequently heard noise is a sniff. Everything

that is not grey — clouds, road, pigeons — is brown: benches, buildings, leaves, bronze soldier and sailor, the figure of Victory perched on the memorial behind them. Traffic and shoppers hurry past. The soldier stands erect, doing his best to ignore the fact that the bayonet on his rifle has long been broken off.

In Bradford, too, where we stop for a lunchtime curry, the bronze soldiers have met a similar fate. Once they must have strode aggressively forward, one each side of the memorial. Now they advance gingerly, as if about to surprise each other in a harmless game of hide and seek. That the bayonet was already virtually obsolete as a weapon by 1914 — ‘No man in the Great War was ever killed by a bayonet,’ claimed one soldier, ‘unless he had his hands up first’ — only enhances the lack. Then as now the bayonets’ function was symbolic and ornamental: without them the sculptures’ internal dynamic is thrown irremediably out of kilter.

In Holborn, by contrast — or, more quietly, in the French village of Flers, where there is an almost identical figure — an infantryman mounts a pedestal of land, rifle in hand, encircled by the vast radius of air that extends from head to bayonet-tip to trailing foot. This framing circle renders the sculpture (by Albert Toft) both more powerful and more vulnerable, extending his command of space and fixing our attention, as if through a sniper’s sights, on the soldier at its dead centre.

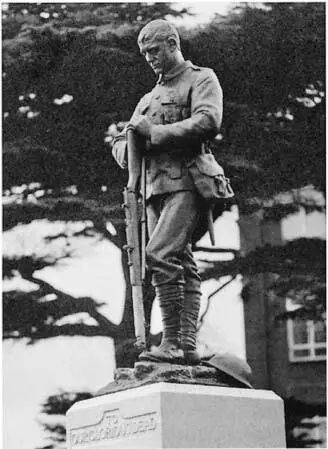

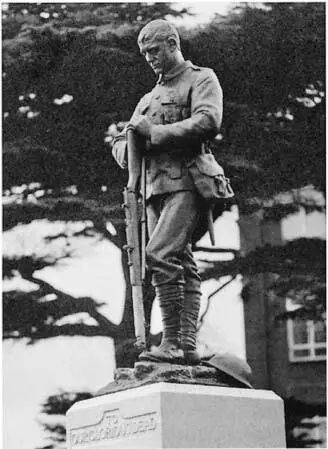

Near Huddersfield, in Elland, the light has called it a day. Twilight is falling through the bare trees. November here can last ten months of the year. The damp grass is covered in damp leaves. On a granite plinth a bronze soldier keeps watch in a drizzle of mist, looking out at the damp road. The collar of his greatcoat is turned up against the coming cold. Old rain drips from the rim of his helmet. Except for the verdigris streaking his shoulders, all colour is a shade of grey. Brodsky:

Leaning on his rifle,

the Unknown Soldier grows even more unknown.

At Stalybridge a soldier slumps into death. His body crumples beneath him but an angel is there; she has been waiting, it seems, for exactly this moment. Berger has described another almost identical memorial in a village in France:

The angel does not save him, but appears somehow to lighten the soldier’s fall. Yet the hand which holds the wrist takes no weight, and is no firmer than a nurse’s hand taking a pulse. If his fall appears to be lightened, it is only because both figures have been carved out of the same piece of stone.

They are all over the country, these Tommies: taking leave of their loved ones (in Newcastle), standing to, resting, reading letters, attacking (in Kelvingrove Park in Glasgow), binding their wounds (in Croydon), helping injured comrades (in Argyll), dying, returning home (to Cambridge). Representing and preserving a sample of the multitudinous gestures of the British soldier at war, these frequently duplicated poses put me in mind of the Airfix soldiers which moulded my taste in memorial art.

They are all over the country, these Tommies..

Elland Memorial

Age may not weary them but the years have condemned. Sundozed and snow-dazed, they sweat in greatcoats in the summer or freeze in shirtsleeves through the long winter months. Sprayed by feminists — ‘Dead Men Don’t Rape’ — and damaged by vandals, all are rotted by pollution. Powerless to protect themselves, their only defence, like that of the blind, is our respect.

Читать дальше