‘And I have never given so little a shit in my life about morality,’ said Laura. ‘So yeah... there you go.’

‘You’re something else,’ said Patrick.

‘I don’t care what the fuck you think of me,’ said Laura. ‘I don’t. I don’t know what you’re doing over there. But we’ll sit here all week if we have to, and you can go wherever it is you want to go. And we’ll stand up in any court of law and swear that we saw Terry Hyland fuck you off a cliff if it means you can walk off into the sunset.’

Murph started whispering to Laura. Patrick listened to their footsteps moving away from him, listened to the sound of tarpaulin being unwrapped.

Laura screamed. ‘Clare!’

‘Jesus Christ!’ said Murph. ‘You sick fuck.’

Patrick laughed. ‘Were you looking for the tools? No. No tools... unless there’s a judge’s gavel in there. But that’s not going to have much of an impact, physically.’

Murph’s footsteps thundered towards the confession box. He hammered a fist against it. ‘You just tell us whatever you want us to do and we’ll do it.’

‘I think I just want you to die,’ said Patrick.

He opened the confession box door.

‘Die?’ said Murph. ‘What the fuck are you talking about — “die”?’

‘Die,’ said Patrick. ‘Jesus Christ, Murph. The fire — it was me. I set the fire. You told me you were going to tell that story, you asked me to run it by you again, you asked me to show you how I’d made all that smoke. And, of course, that wasn’t good enough for you. You had to go bigger and bolder. And that suited me down to the ground. I was fucking sick of you all, you fucking assholes. Good enough to help you with the entertainment, not good enough to be part of the night, though. Clare going crying to her fucking French teacher about what I was doing in the library and she goes to Consolata and she fires me, then, and how could I explain that to the mother, and then Jessie... and I’d listened to Jessie enough times, the two of us fucked in the head with all that went on and me helping her out so many times, hidden away, because I’m the freak all of a sudden when all she’d ever said was that the two of us were the same like we were the broken halves of the same child and then she’s gone like everyone else and all she wants to do is get pasted, and stand me up, so she can hang out with you pricks, laughing at me behind my back, but I’m good enough for you now, amn’t I?’

‘Well, you got your accent back, didn’t you, you prick?’ said Murph.

‘Patrick, what are you talking about?’ said Laura. ‘You were good enough for us after the—’

‘After it!’ said Patrick. ‘After it!’

‘But we’ve been friends for years!’ said Laura. ‘I don’t get it! You saved us! You changed your mind in the end! So why are you—’

Patrick groaned. ‘You’re all so fucking nice! It’s painful. I didn’t fucking save you — I got caught! By Consolata. She — as she put it — “gave me the gift of being a hero” to see if that would straighten me out. And I did enjoy it. But not in a nice way. In a fuck-you kind of way. Obviously. Anyway...’ He reached into the confession box, took out a blue container of kerosene and unscrewed the lid. ‘Let’s try this again.’

‘Try what again?’ said Laura. ‘What are you doing?’

Patrick poured the kerosene into the confession box, then all across the floor and on to the rolled-up altar carpet, and in a trail as he backed out through the sacristy door.

Laura and Murph smelled it at the same time. Laura screamed.

Patrick reached into his jacket and pulled out four loose pages from the notebook. One page had the same line repeated from top to bottom: NONSENSE.

On the next page, the ink was diluted in places.

I MET MY DAMAGED REFLECTION AND THERE WAS NO MIRROR IN BETWEEN. I COULD REACH OUT AND TOUCH ANOTHER ME. SO WHAT SHARDS ARE MAKING ME BLEED?

The next page said:

WHAT BRIDE OF CHRIST ARE YOU? THE ONE STANDS AROUND SMOKING IN HER WEDDING DRESS. IN THE FIRES OF HELL.

The last page had one question:

WHAT’S THE PENANCE FOR THIS, MAMMY?

He took the pages, twisted them tightly, bent down and dipped them in the kerosene on the floor. Then he walked over to the confession box, took out a lighter, flicked up a flame, and held it to the paper.

He stood, staring, as the flames took hold.

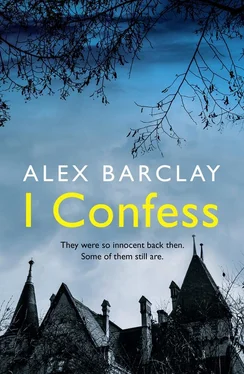

He watched his words burn. ‘I confess?’

Castletownbere

July 1991

Mrs Lynch stood in the tiny back yard, with a basket of wet laundry sheets at her feet. In front of her, a double sheet was folded over the washing line, letting sunlight through its threadbare patches — the scars of her painful writhings. Sunlight... through the places her heels scrambled against, through the places her knees would burn when her body was shunted forward.

She had always hidden her body, but that hadn’t stopped men wanting what lay beneath the armour of her clothes, layers she had started to build since the first time her uncle had quietly opened her bedroom door and walked the floor to pull back her covers. Halfway across, there was one floorboard that creaked, and it was either that or the smell of whiskey breath that would waken her. It was never his touch. She was always awake before that, always had time enough to feel the terror, and over the years, to train herself to shut it down.

Patrick’s father had a different approach. She met him when he was sixteen years old and she was eighteen, gone from her family, slowly beginning to hope that one day — there was no rush — she could get married, one day, she could feel safe in a man’s arms. Patrick’s father lured her in with tenderness. But only one evening of it. As soon as she had given in to her hope, he did everything he could to prove to her that it was pointless.

It didn’t matter that she had only ever presented herself to the world without enhancement or adornment; no make-up, no jewellery, no perfume, hair cut by a barber, eyebrows unplucked, nails clipped short, but bare. All she had ever been was scrubbed clean, looking younger than her years. Maybe that’s all it was, she thought. She was scrubbed so clean that to dirty her was a special triumph.

It had been a month since Terry Hyland had first knocked on her door for a reason other than to fix something. When she opened it, he was standing on the street, looking at her like she had called him there. He broke the silence of her confusion by telling her he had something to say to her, asking her could he come in, and she let him, but she didn’t know why. She brought him into the kitchen and put the kettle on out of politeness.

‘I learned to read,’ he said.

Mrs Lynch heard what he was saying, but couldn’t match the expression on his face to the words. He was saying one thing, a good thing, but there was a darkness in his eyes that spoke only of bad things. A chill started a slow crawl across her back, then quickened, spreading out like tentacles when she saw Terry take out Patrick’s notebook from his jacket pocket. She stared at the thing that she and her son had never spoken of, the thing she had taken from his desk drawer the night of the fire that had brought her to her knees by her bed to pray for his soul.

Terry held it up and tapped the air with it. ‘He’s some fucked-up prick.’

Mrs Lynch’s gaze followed the notebook as he slipped it back into his pocket.

‘And do you know who taught me?’ said Terry. ‘To read.’

The tick of the clock was the only other sound in the room.

‘Mrs Brogan,’ he said, nodding. He shrugged. ‘I was doing a job in the house, and, sure, she could see straight away that I couldn’t read. A woman like her would know all the tricks. She said there was no shame in it. She was fierce impressed a man my age had got so far without it, saying I must have a fierce memory because she knew I had to. You cover it up, I suppose. Cover it up.’

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу