Silence, breathing. Silence, breathing.

“Wait, wait,” he said thickly, his tongue slow and lugubrious. “Sully?”

“We got to go a little quicker,” Sully said. “I only got two minutes.”

The man tried to rub his eyes, bringing a sharp rattle when his wrists hit the limit of their chains, startling him. He’d just woken up, they had him laced on some sedative, something.

“How’d you, how’d the fuck you get in here?”

“Introductions,” Sully said, ignoring him. “You know who I am, George. But you seem to be telling everybody you’re Terry Waters, your schizoid elementary-school buddy from Oklahoma, though you haven’t seen him in donkey’s years. You’ve been back by there, though, haven’t you? You went to see them, Terry and his dad. You drove right up there to the door. Did his dad tell you Terry was dead, buried out there in the woods by the creek, or did you figure that out all by yourself?”

The man coughed, cleared his throat. “Okay, no, wait.”

He blinked, the eyes still cloudy. Sully tried to set the man’s features in his mind’s eye. It was difficult to get a fix, the man sitting down, wrapped up. His hair and bronzed features the only color in the all-white room.

“Didn’t just happen to kill Dad, too, did you,” Sully said, “so that then you’d have Terry’s identity to yourself? I mean, the man had been dead three days when he was found. You choked him out, you know, I don’t know there’d be a lot of evidence of that.”

This time, the man in the jumpsuit reared back, regarded Sully as from a great distance, as if he’d been speaking to him through a long, dark tunnel, and only now could he make out the words. The eyes gained focus. For the life of him, Sully would swear he’d just offended the man.

“You, what you got to understand is, see, Sully, you don’t know everything,” he said, voice still thick, but clearing up now. “Sully. Sully. Look. This has gotten sort of fucked around. We got a bond, see, our mothers. I got a story to tell, you got stories to, to write. Us. Injustice. There are larger-”

“You tried to shoot me,” Sully said, voice rising. “Bond, my lily-white ass.”

“-themes to what we’re, no, see, no.” A deep breath, pulling it from the base of the lungs, like he’d learned it in yoga and he was restoring his balance here. Another deep one. “I’da wanted to kill you, I would have. Had the drop. I just wanted to get your attention. I wanted to get-” he stopped. “I shot some glasses on your table. I wanted us to meet, before they found me. See, what came to me,” another rumbling cough rattled his chest, “seeing all that shit on TV? They wanted to kill me. They did not want to take me alive. Or they wouldn’t be able to, just some trigger-happy asshole with no training, blam blam and too bad for me. So it dawns on me, what I needed to do is make sure that I’m safe. Make sure that they arrest me and not shoot me like a dog. I needed a witness , somebody to make sure they didn’t blow my head off and then put a pistol in my hand and call it self-defense. And who better a witness? Who better to keep them honest? Who better to tell the tale?”

He gestured forward, palms up, hands open, extended fingers, a wan smile. “You.”

Sully looked at him. “George?”

“Why do you keep calling me that?”

“That is bullshit.”

Waving the hands, no-no-no. Warming up to it now. “It isn’t. It really isn’t. You were there at the beginning, with Edmonds. You saw. Only you. Only you will understand. Can understand.”

“Understand what.”

“The nightmare.”

“Okay, look, let’s cut the crazy-man, mystical bullshit. Superior Court, fucking Glen Campbell. I’m not here for the circus. I’m here-” and, on instinct, on the fly, he changed. He’d been about to demand an explanation, or what passed for an explanation, on the murder of Edmonds. That was why George was here, that was the linchpin upon which the rest of this all revolved. But he saw playing the hard-ass wasn’t the right option, not now.

“I’m here,” Sully said, making himself slow down, his voice softer now, sliding to the floor, sitting cross-legged, back against the door, keeping eye contact, looking as deeply into the man as he dared.

“I’m here,” he repeated, faintly now, bringing it down to imitate an intimate conversation, “to hear about what happened to your grandmother. Miriam. The knife.”

“Miriam, the knife? Isn’t it supposed to be ‘Mack’? You know, the song?’”

Gently, again. The word had popped into his mind, gentle , and your instincts were there for a reason. Sully curled his fingernails in against his palms. The man in front of him, he wasn’t the killer in the Capitol. He was the boy in the back of the patrol car. He was the boy bathed in blood. The horror this man’s life had been. Gentle. Nobody had been gentle with him in, what, how long? Sully had a flash vision of George leading prostitutes into hotel rooms, rough sex, taking them from behind, handcuffs and blindfolds, sex doubling as hostility.

And it slipped into his mind, as natural as the Mississippi running into the Gulf, Alexis whispering in the dark with me not to me , the way he had needed to take Dusty on her knees, the hands cuffed behind her, the others he couldn’t remember, the ones who had loved and encouraged it and the ones who had complained, the way he tended to black out afterward, not just fall asleep.

We have a bond our mothers only you the nightmares…

And George, having read about his mother, not even Nadia, had him pegged to the marrow.

“Miriam,” Sully forced himself to say out loud, to snap back to the urgency of now. What did he have remaining, sixty seconds? Less? “You said her name in court the other day, George. In C-10. You slipped, brother. You were doing your crazy-man rant, and you shouted ‘Miriam,’ at the judge. Party’s over. Miriam Harper was your grandmother. You’re not Terry Waters, that was a kid you played baseball with. Rode horses. Your grandmother, Miriam, she slit her throat in a two-story country house outside of Stroud, Oklahoma. You called the sheriff. She bled out on you in the back of the patrol car. Miriam. It wasn’t your fault, George. But you got stuck with it. A terrible goddamn thing.”

The man staring at him, the accordion playing forgotten, his hands frozen in place. Stammering, the balloon of self-confidence punctured, all the air escaping. “You, you, are so off the, what is it, the-”

“Your granddad took you to the funeral home,” Sully said, quietly, as if someone might overhear. “William. He didn’t take you to the funeral because there wasn’t one.”

Softly as the benediction now: “It’s over, George. I know. I was there. The old house. Your old room. Tell me about her. Miriam.”

Nothing but emptiness, the eyes gone vacant, hollow, a canyon, still locked onto his.

“Tell me about what Barry Edmonds did that you had to kill him. Tell me about your mother. Frances. I can help. We got this bond, George. It’s only me. Only you. Tell me about Frances, George. Tell me who killed your mother.”

George Harper stared at him. A single tear, shiny as a diamond, seeped from the inside corner of his right eye. And then, in a sudden flash of movement, he was barking, bellowing, weeping, shouting, and crying all at once, yanking on his chains, stomping on the floor, spittle flecking from his mouth, howling, the sound tremendous in the room, the man losing his balance, nearly falling, careening into the wall.

The door behind Sully burst into his back, the orderly shoving it in, knocking Sully to his side, stepping in over him. Before Sully could roll over, another orderly-larger, beefier-stormed in behind him. Sully seeing them from the floor, the pair of them looking fifteen feet tall, outlined in grotesque proportions against the all-white environment.

Читать дальше

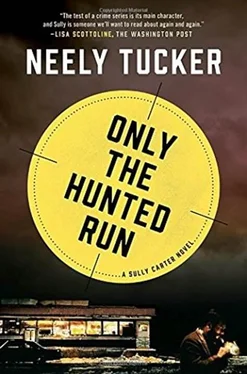

![Джон Макдональд - The Hunted [Short Story]](/books/433679/dzhon-makdonald-the-hunted-short-story-thumb.webp)