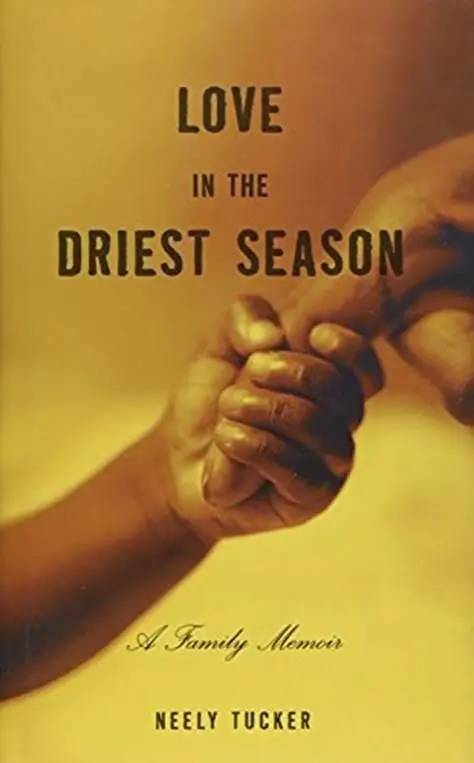

Neely Tucker

Love in the Driest Season

© 2004

Photograph by Jon Jones

For Chipo, who lived.

And

In memory of

Tatenda Jeselant, Godfrey Muparutsa, Shingirai Nyamayaro, Munashe Tsekete, Memory Chinyanga,

Joe Bhebhe, Frasia Chateuka, Ashley Mhlanga, Caroline Razo, Collins Murehwa, Clara Mlambo, Sandra Mahohoma, Rejoice Neshuro, Nyasha Dziva, Abigail Mazviona, Tadiwanashe Mtero,

Sarah Chiwasa, Mable Kachembere, Ibrahim Hodzic, Margaret Wanjiru Kangi Mungai,

and

Robert and Ferai,

who did not.

Nothing lives forever but/ the love

that bears your name.

– CASSANDRA WILSON ,

Solomon Sang

Something happened to me inside the orphanages.

– JAMES NACHTWEY ,

Inferno

BY NOON, the ants found the girl-child.

Left to die on the day she was born, she had been placed in the tall brown grass that covers the highlands of Zimbabwe in the dry season, when the sun burns for days on end and rain is a rumor that will not come true for many months. She had been abandoned in the thin shade of an acacia tree, according to the only theory of events police ever put forth. There were no clues as to exactly when she was left there, or why, or how, or by whom. She just appeared one day, like Moses in the bulrushes.

Patches of dried blood and placenta streaked her body. Her umbilical cord was still attached, a bloody stump dangling from the navel. A colorful yank of fabric, such as might be found in a store that sold such things by the yard, was wrapped around her torso.

Dozens of miles from any paved motorway, and nearly a mile from the nearest village of mud-and-thatch huts, she lay hidden in chest-high grass. The ragged clumps of acacia reached overhead. In the first glow of day, when night was fading but the sun had yet to climb above the horizon, it was a place of shadows and limited vision.

The ants came from everywhere.

They set upon the blood and the remnants of the placental sac. Dozens, if not hundreds, poured over the fleshy stump of the umbilical cord. They began to eat her right ear.

The girl-child screamed.

The sun rose in the sky.

The hours passed.

There is a wind that moves through the high grass at that time of year. It makes a whisper of its own, a feathery undertone that rolls over the landscape and drifts through the trees. Some people from the village who were walking along the footpaths thought they heard a child’s cries above the rustling, but no one stopped. There are many portents the ancestral spirits sometimes use to communicate with the living, and the mysterious, disembodied voice of a child on the upper reaches of the breeze carried an ominous sense of foreboding. The women kept walking, making for a concrete-block country store several miles away. They went there for sugar and salt and dry goods. Men went for the fat brown plastic jugs of traditional beer that smelled sour and left seeds between the teeth, but which carried a haze that melted the corners of the afternoon.

Late in the day, the sun fading away to the west, a woman named Constance paused on the path. She listened above the breeze. She waded into the grass, parting it with her hands, stopping, listening again. She moved to the clump of acacias. What she saw sent her stumbling backward, and then she turned and ran for the village. She found Herbert, the village elder, and dragged him back by the sleeve.

He moved into the grass, reached under the branches, and picked up the wailing infant. Then he sent a young man running for help.

“She was very dirty; there was dust all over her, her face. And the ants were running over her head, really biting into her ear,” he would later say. “She was crying, crying. Eh-eh! Crying all the time. I picked the ants off her. We brushed the dust from her, though we could not get her clean.”

In the time of AIDS in southern Africa, adrift on the tide of the deadliest disease to wash over humanity since the bubonic plague, the child who would change my life hung on to Herbert like a survivor from a shipwreck. She was one of an estimated ten million African orphans whose lives in the waning days of the twentieth century had been altered, if not devastated, by the AIDS epidemic. By the winter Herbert held her aloft in the late afternoon sunlight, Zimbabwe had become ground zero of a worldwide crisis. About one in four Zimbabweans between the ages of twenty-five and forty-four was thought to be HIV-positive, the highest rate in the world, along with next-door Botswana. The government and various United Nations agencies estimated that five hundred people were dying of the disease each week, a fatality every twenty minutes, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. Newspaper obituary columns were filled with memorials to young people who died after a short illness, a long illness, a sudden illness. The morgue in Harare, the Zimbabwean capital, began to stay open all night.

And still the bodies came.

No one knows exactly how many, for few of the dying ever knew or admitted to having the disease. Most, in fact, had never been tested. But the death toll was nearly some six hundred thousand since the disease was first recognized in the early 1980s. Zimbabwe’s average life span plummeted from fifty-six years to thirty-eight, one of only five countries in the world to have a life expectancy of less than forty.

Young parents died in the tens of thousands, giving rise to a corresponding tide of orphans. There were perhaps 200,000 in 1994. Four years later, in a nation of 11 million, there was a flood of 543,000 children who had lost either their mother or both parents. This overwhelmed the traditional African social welfare net, the extended family. Zimbabwean uncles and aunts, grandparents, and cousins came forward in astounding numbers, but too many young parents had died. By the winter of 1998, children were being abandoned in record numbers across the country and the region. In Lusaka, the capital of neighboring Zambia, there had been an estimated thirty-five thousand street children in 1991. By 1998, there were more than seventy-five thousand and the number was climbing. In a remote province of Zimbabwe, Herbert was holding one of dozens of infants who had been flung into garbage bins, slipped into sewers, or left behind in open fields in a six-month period in that province alone. It was anyone’s guess how many had been abandoned in the entire country.

The scale of death, and the depths of misery it entailed, defied the imagination even for someone like me, who had chronicled some of the world’s deadliest conflicts for the better part of a decade. Before joining the Washington Post, I was a foreign correspondent for the Detroit Free Press, first assigned to a roving post based in Eastern Europe in 1993, then to sub-Saharan Africa in 1997, based in the Zimbabwean capital of Harare. I roamed more than fifty countries or territories in seven years, from Bosnia to Sierra Leone to Congo to Iraq to Rwanda to Nagorno-Karabakh to southern Lebanon to the Gaza Strip, a steady parade of greater- and lesser-known wars, riots, and rebellions. As the body counts multiplied, I tried to ignore the physical, mental, and emotional toll such work had begun to exact from me. My body had been riddled by typhus, food poisoning, and repeated viral infections; my hair turned completely white. The steady stream of violence had worn away my natural sense of compassion to the point where I could cover almost any horror but felt very little about anything at all. Sleep was either a blessed blank space or a disturbing hallway of nightmares. I woke up one morning to discover I had lost my religious faith, as if it were a suitcase left behind in a distant airport.

Читать дальше