Tolevi got up and walked in the man’s direction. He stared at him, daring him to meet his glare. But the man feigned interest in a woman a few seats away, never turning in Tolevi’s direction even as he passed directly in front of him.

Tolevi went into a souvenir shop, then continued down the hall to a small restaurant. He studied the menu, then went in, taking a seat at a table in the back. When the server came over, he ordered in Russian.

The young man did not follow. Tolevi’s seat could not be seen from the hall; he scanned the small room, looking for others on the surveillance team, but there were no likely candidates.

The safest thing to do — the smart thing — would have been to call off the pickup. He could go directly to the gate, board his plane when it was ready, and leave. The SVR might not let him leave, but when they searched him, there would be nothing incriminating.

Not that the Russians ever needed evidence.

Tolevi eyed the kitchen, fantasizing a dramatic escape. It would work for James Bond, but not for him, unless he lucked into an Aston Martin on the apron.

The young man with the bad haircut was nowhere to be seen when Tolevi exited the restaurant, but that only stoked Tolevi’s paranoia. Now everyone he passed could be an agent.

Anyone or no one. You’re letting your imagination run wild.

Tolevi found the bookshop and went in. Casually lingering near the magazine rack, he checked his watch. Forty-five minutes to boarding, which was when the exchange was supposed to take place.

He bought two magazines. A man, obviously Russian, watched him as he paid. The man was well built, in his thirties — the profile of an SVR supervisor, Tolevi thought.

No. Most supervisors are older, with potbellies and poor grooming.

Still…

Magazines in one hand, briefcase in another, Tolevi made his way down the terminal hallway to a gate where a plane was just boarding for Moscow. Glancing over the crowd, he picked out a middle-aged man who did look, in fact, like an SVR supervisor — a dark jacket over black jeans, with a badly wrinkled white shirt. Tolevi slipped through the line, then brushed against him.

The magazines fell from his hand.

“Excuse me,” said Tolevi loudly. He handed him the magazines. “I’m sorry.”

“These are not mine,” protested the man.

Tolevi was already walking briskly away. The man said something else, but Tolevi couldn’t hear. He saw a woman darting toward the gate.

An agent? Or someone who had just heard the call to board?

Tolevi’s heart was pounding. He crossed to the men’s room, found the urinal at the far end, and put down his briefcase as he unzipped his pants. There were three other people in the restroom, all at the urinals.

Four — an Asian-looking gentleman dressed in a business suit came in, pulling a wheeled carry-on and a briefcase identical to Tolevi’s. He chose the urinal next to his.

Tolevi fixed his pants, then left, quickly grabbing the briefcase from the floor.

The other man’s.

Outside, his plane was being called. Tolevi walked to the gate.

The man with the bad haircut was near the gate, waiting. Tolevi took out his ticket.

He smiled at the man. The man frowned.

Safe. I was just paranoid.

He held the ticket for the gate attendant, who checked off his name on her clipboard, then waved him up the jetway.

Tolevi glanced at his ticket to check where his seat was.

His hand was shaking.

Relax. We’re done here.

“Gabor Tolevi!”

His name boomed in the tunnel. Tolevi turned. The woman he had seen earlier was behind him, leading two tall, much younger men.

SVR, all of them.

“Yes?” he said.

“Let me see your briefcase.” The woman’s voice was just like a man’s.

Tolevi hesitated. “Why?”

“Open it.”

“Here,” he told her, handing the briefcase over.

She grabbed it and clicked open the clasp. The two men stopped behind her, stationing themselves to block off escape.

Stuck here. Better to talk yourself out of it. Call Keisha, the Hound, get him to help.

The handler would never take his call. He was on his own.

The woman pulled out a newspaper, then passed her hand all around the interior of the briefcase. Except for the paper, it was empty.

“You may go,” she said, handing it back. “A mistake.”

“No need to apologize,” said Tolevi. “Have a good day.”

Cambridge — nearing 9:00 p.m.

The false alarm dampened everyone’s spirits but not their appetites.

“I could smell that pizza two blocks away,” said Jenkins as they returned to the van.

“I figured you’d all be hungry,” said Flores, who’d brought two pies. “Mushrooms and plain.”

Chelsea shook off the offer.

“You gotta be hungry,” said Jenkins. “Come on.”

“Not for pizza,” she told them.

“Perfectly balanced food,” said Robinson. “Fat, carbs, protein, tomato sauce. Doesn’t get any better than this.”

She rolled her eyes. Jenkins was right — she really should eat — but not pizza.

She looked at the video console, which showed the ATM they had under surveillance. It was all on the FBI now.

“Nothing going on,” said Flores. “Only two people have used it all night.”

“We’ll keep surveillance on all night,” said Jenkins, “but it doesn’t look good.”

* * *

At precisely five minutes to six, Jenkins’s second in command knocked on the door of the van, ready to begin the day shift. With him were two other FBI agents and a young Smart Metal employee, Jason Chi, who worked in the UAV division but had a strong background in AI. It took less than three minutes to brief them; Jenkins checked in with the surveillance teams, who were also being replaced, then walked Chelsea out to her pickup truck.

“See you tomorrow night?” she asked.

“Absolutely.”

Riding back to the task force headquarters, he checked his messages. His brother’s wife had called twice during the night; both times she’d tried to say something but couldn’t get it out. Too tired to call her back, he told himself she’d probably be sleeping. He checked his official e-mail quickly, then left for home.

Two hours after he arrived, Dryfus woke him with a phone call.

“They struck overnight,” said the tech supervisor. “I just got a call from Bank of America.”

“Son of a bitch. Was it the machine we were watching?”

“No. And none of the ones we staked out,” said Dryfus. “But…”

“Yeah?”

“It was in the next batch on the list. We just missed it.”

Jenkins collapsed back on the pillow, completely defeated.

Boston — later that day

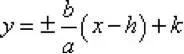

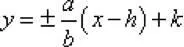

“So as we know, the graph of a hyperbola gets nearly flat as you move from its center. This part is called the asymptote of the hyperbola. And we use these equations to graph…”

Borya watched the teacher slash his chalk across the blackboard, dust flying. She liked that — all of the other teachers used smart boards; Mr. Grayson was old school.

She saw the graph before he drew it, two slight curves across the x axis, one kissing the y axis, the other, a mirror image, off to the right.

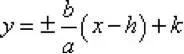

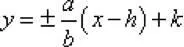

You could flip it:

Mr. Grayson continued spewing chalk, almost frenetic as he explained the math behind the graphs and calculations. There was something about calculus that made even boring people, like Mr. Grayson, excited.

Читать дальше