My hand had paused at the sight of the painting resting on the easel. I had not asked to see it, had not bothered to look at it, the last time I had been in his studio. A part of me, later, had wondered whether he had even been painting at all, whether it had truly been my portrait his brushstrokes had created. But about this, at least, he had been honest.

A strange mix of blues, the shades of which I could not name, the painting displayed my features in startling clarity. It betrayed, I thought, just how closely he had been observing me these past weeks—for surely he had not seen all this in just the few moments that I had sat for him. There was something intimate, something that suggested a relationship existed between the artist and the subject. I knew little about art, but I had the sense that it was something that should make one feel, should make one think.

It was already approaching evening, and I struggled in that moment, watching as the fading light cast its beams across the painting, caught between the desperate need to get away, from the studio, from Tangier, and yet hesitant to leave. It seemed all too sudden, as if I hadn’t had time to prepare, to allow myself to mourn. Part of me wanted to leave it there, as a reminder, proof that I was once there, that I had loved Tangier, had loved Alice, in that moment. That it had all meant something. But then I thought of the painting remaining there for Youssef to look at, believing he had bested me—even if the illusion would last only for a moment or two longer. The idea unsettled me. I thought too of the police, who would find it, who might pause long enough, particularly if Youssef decided to point in my direction, when he realized his Alice was not the Alice. It would not do, I realized.

I had reached out and taken the painting.

I now paused before lowering the blouse over my head, my eyes flickering to the mirror, to what I saw reflected there. A young woman, handsome enough, but nothing that clamored for attention. I thought of Youssef’s painting—of the shrewdness that he had captured. I relaxed my face, watching, working to soften my features, to rearrange myself into a girl called Sophie Turner, though I had already begun to suspect that she would not fit for much longer—her worth, her purpose diminishing with each and every step that I took.

I reached for my suitcase, taking one last look around the apartment.

We could have been happy here, I thought sadly.

I closed the door and exited onto the streets below.

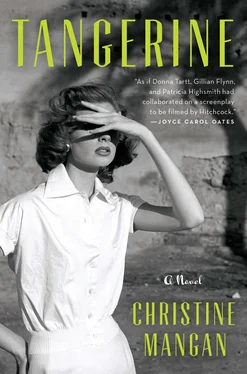

I INHALED, TAKING IN THE SCENTS of Tangier, reminding myself, even as I did so, that it might be the last time I found myself on her shores again. As I moved through the markets, my eyes trailed over the tall mounds of spices, from the brilliant shades of squash-colored turmeric, to the crushed rose petals and overflowing baskets of whole peppercorns. If I were a painter, an artist, this is where I would spend all my time, I decided. There was no better place to observe Tangier.

And then, though I knew it was silly, that it was entirely too sentimental, dangerous even, I made my way toward the Kasbah, toward the tombs and the cliff and the water beyond, one last time. In the end, I could not stop myself.

Standing atop the cliff, determined to take in one last view of Tangier, I was struck by her beauty, by her mystery. I thought of the tale that Youssef had told me. The one about the beautiful woman luring men to their death. Perhaps it wasn’t some mysterious woman at all, I thought now, perhaps it was simply Tangier, Tingis. For in a way I too had experienced a sort of death upon her shores. I had come to her as one thing and was now leaving as another. This metamorphosis, it seemed, was dependent on rebirth, and so death must also be a part of it, the two inherently linked.

I removed the painting from under my arm, gave a quick look around to make sure that no one was watching, and released it into the water below.

Lucy Mason had outlived her usefulness at last—though she had never been particularly useful to begin with, I thought with disdain. Born poor, uneducated, to a family that couldn’t be bothered to care, in the end her survival past the age of ten was a miracle in itself. That she had found a way to survive, in that garage, alone with her father, with the other men, that she had picked up one book and then another, teaching herself to read, to write, to earn a scholarship that promised her something more, something better—it should never have happened. She should have died long ago, just like her mother, another forgotten life, another forgotten death. With no one left to mourn, to remember. I stood for a moment or two longer, imagining the waves as flames of a fire, watching as they lapped, as they drowned and devoured the last and final traces of Lucy Mason.

I moved away from the cliffs, realizing that time had been slipping away from me, that the ferry would soon be arriving. Heading toward the port, I kept my eyes focused, kept my gaze averted as I walked, avoiding those very same spots where only moments before I had walked, eagerly, greedily, hungry for a reminder, a souvenir, of Tangier. I thought of that first day, of the sellers that had greeted me, called out to me, trying and failing to get me to part with my money. I saw them again as I moved toward the port and then—yes, I knew it was him—that very same Mosquito who had pursued me through the streets as I had sought to find Alice’s flat that first day, who had slipped away only moments before I had stood beneath her balcony, watching her from a distance.

He moved toward me now, a smile emerging on his face. “Madame needs a tour guide?” he asked eagerly.

I shook my head and indicated the boat, just beyond.

He nodded in response and opened his jacket, revealing a hidden layer of cheap, shiny bracelets and rings, the kind that would no doubt stain one’s skin green within a few days. “A trinket, madame,” he offered. “To remember your journey.”

I nodded, reaching for my last few francs. “Here,” I said, handing over the coins.

He rewarded me with one of the bracelets.

“A reminder, madame,” he said, smiling. “Of your time in Tangier.”

I thanked him and headed toward the port. As I boarded, I let the trinket drop from my hand into the Mediterranean, though I did not bother to watch as it sank. Letting out a small laugh, I thought of what I had wanted to say to the Mosquito. That the bracelet, or any other of his treasures, was unnecessary. That I didn’t need anything to remind me of Tangier, of her.

After all, I was a Tangerine.

I would never forget.

IN SOME WAYS, MALABATA PRISON WAS NOT SO GRIM AS I HAD anticipated.

Sitting on the eastern outskirts of the city, it stood, a vast grand building rising up in front of me so that I was immediately reminded of the Hotel Continental. I felt a chill run through me. The two structures could not have been more different, and yet there was something in them that felt strangely familiar, a sense of the imposing stature that radiated from both.

Inside I was conducted through a series of hallways before passing at last into what appeared to be some sort of makeshift cell, held apart from the rest of the prison.

Youssef stood when I entered. “I am so famous now they decided I must have my own room,” he said by way of greeting, indicating his surroundings. He smiled, watching as I assessed the tiny enclosure, the prison within a prison that they had created for him.

I smiled weakly in response, though I suspected he knew the truth. For while Tangier could most certainly be a dangerous place, I had learned from John that most of the criminals within the walls of Malabata were thieves and pimps, the most common offense the smuggling of kif from the mountains and into the city. A dangerous criminal like Youssef would not sit well with either the prisoners or the guards. And so they had cordoned him off, creating a room that held him apart from the rest of the populace, with only one solitary window for company.

Читать дальше