The landline’s ringing in the hallway, but the arguing from earlier starts again in the kitchen.

‘Shall I get that?’ I shout, but no one replies.

I walk towards it, but it stops ringing. I pick up the receiver and press 1471, jotting down the mobile telephone number.

In the kitchen, Mum, Nadia, Emma and Matt are sitting round the table.

‘You’ve missed a call,’ I say. ‘I wrote the number on your pad.’ No one acknowledges me. ‘What’s going on?’

‘Matt, you can’t go around questioning people. It’s up to us,’ says Nadia.

Emma’s sitting next to her, cradling a cup of black coffee. Her eyes are barely open, the skin around them puffy.

‘What are you talking about, questioning people ?’ I say. ‘What’s going on?’

Mum’s rubbing her temples with her middle fingers.

‘Matt wants to question Mr Anderson at the newsagent’s.’

‘But the police haven’t questioned him yet, have they?’ he says to Nadia.

‘They’re not reporting back to me with every line of questioning. What they will do is let us know if they have any vital information.’

Them and us. Nadia chooses her words and allegiances to suit the circumstances.

‘That’s not enough,’ says Matt. ‘That man… he’s only lived here, what… three years? What does anyone know about him?’

‘We would have searched the premises.’

‘Oh, we would have, would we ?’ Matt puts on his trainers and stands. ‘You can’t stop me going for a walk, can you?’

‘Of course not,’ says Nadia, a lot calmer than I’d be. ‘But I will have to call in help if you harass this man.’

Matt walks out of the kitchen.

‘Call for fucking help then.’

The front door slams behind him.

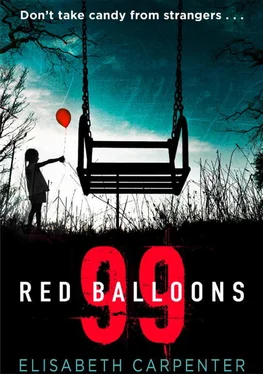

Maggie

I’m nearly at the newsagent’s. I need to see more pictures of her. It’s been three days since I last went out. It’s not raining, but I’m wearing my mac anyway. I don’t know why I didn’t look out of the window before I came out. It’s sunny, bloody typical. It’s never usually warm in October; I’m sweating in this stupid coat.

I shouldn’t have come outside. It’s making me think too clearly, but I need to see her in black and white, to feel the pictures between my fingers. It’s not enough seeing the news on television. I’m getting the sickness again – that’s what Sarah used to call it when she was obsessed with a boy at school. She knew it was happening, but couldn’t do anything about it. It’s how I feel about this; it makes me feel closer to Sarah.

I open the door to the newsagent’s.

‘Morning, Maggie. Not seen you in—’

‘Morning. I’ve been ill.’

Hopefully my tone will put her off talking to me again.

‘Are you okay? You haven’t been yourself this past week.’

‘How would you know? You haven’t seen me for days.’

I wish she’d just shut up.

I pick up three copies of each newspaper, placing each on the counter as I move along the rack. I’ve brought my shopping trolley so carrying them home won’t be a problem.

‘I’m sorry, Maggie. I should have realised. Sandra said you get awfully upset whenever there’s a missing child.’

Sandra.

That bloody woman. I’m sure she was put on this earth merely to test my patience – to examine every single movement I make. I can feel it bubbling inside me. The rage is almost at my mouth. I have to stop and breathe before it escapes.

I slam the last three copies of the Express onto the counter.

‘Just these, Mrs Sharples.’

‘I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to pry.’

I should have exploded while I had it in me – let her have every angry word I want to throw at the people who live in this village – all their pitying glances, their whispers of That poor, poor woman, she’s got nothing left . But it would only give them something else to yak about. I’ve lived with this for too long. Once I let them have it, I’ll know that I’ll have finally lost it – and I came too close then, far too close. I’ll have to keep myself in check.

‘How much will that be?’

She pushes the stack of papers towards me.

‘You can have them. Please… on me… no charge.’

Breathe, breathe.

I open my trolley and carefully lay the papers inside. I place the money on the counter.

‘I do appreciate that, Mrs Sharples, but I don’t accept charity. Never have, never will.’

I turn and pull my trolley.

‘Maggie. Please call me…’

She doesn’t bother to finish her sentence.

How has using scissors become so difficult? My stupid hands. It has taken me nearly an hour to cut out twelve pictures. Of course, it didn’t help that the photos are so bloody small. The newspapers haven’t printed many pictures of Grace Harper’s family – they’re not as important as the little girl. But they’re important to me.

I’ve placed the grainy black and white ones – most of them duplicates – around the big picture of Sarah in the middle of the coffee table. It’s like looking at lots of little Sarahs – the likeness is incredible. Is it the sickness clouding my thoughts – making me see things that aren’t there? No. It can’t be.

The photo in the middle is the clearest I have of Sarah. We didn’t bother taking photographs after Zoe went missing – why would we? There was no happiness in this house after that – no good news to celebrate and document. With each year Zoe was absent, Sarah faded further away. I blamed the booze, but perhaps using drink was how she lasted so long without her daughter.

She only started drinking after Zoe was taken. I don’t think she was depressed as such, just so desperately sad. I can’t imagine my own child being taken from me like that, the not knowing where she is. It’s bad enough when it’s your granddaughter – but your very own daughter who’d grown inside you. The thought is horrific.

I get up from the settee, using the coffee table as a crutch. I’m so tired: mind-tired, body-tired. Why am I still living? If I were still a religious person, I’d believe I was being tested, but I left God behind years ago – or did God leave me? I keep wondering what I did so terribly wrong in the past to make everything turn out like this, but I can’t think of anything. All those petty little things I made up in confession as a child: thinking bad thoughts about my parents, not helping with chores. Maybe these weren’t the sins they were looking for, because now I question my very being. Perhaps I just wasn’t good enough as a mother.

In the kitchen, there’s a bottle of sherry, half-empty, from a Christmas too long ago. How long does that stuff last? It’s behind cans of prunes, peaches, and a little pile of tinned pies. Ron loved those pies, but I can’t stand them. I don’t know why they’re still there. Comforting, I imagine.

The neck of the bottle is crusted. I put it to my nose: it still smells like sherry. It’ll be fine. I grab a tiny glass from the cupboard and take it into the front room. I’ve never been a drinker; never had more than a tot at Christmas. I’m usually in bed by seven – do people drink in the evening to quash the loneliness?

I land further from the table than I thought and have to shuffle with the bottle and glass in my hands. If anyone could see me, they’d think me ridiculous, a lush. The lid grates on the crust as I unscrew it. I hold up the glass after it’s filled. It still looks like sherry. It still tastes like sherry – or what I remember sherry to taste like.

It doesn’t take long to feel its heat. A fake warmth, but a warmth nonetheless. That’s why this stuff is evil. I stroke Sarah’s cheek on the photograph. My poor darling girl.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу