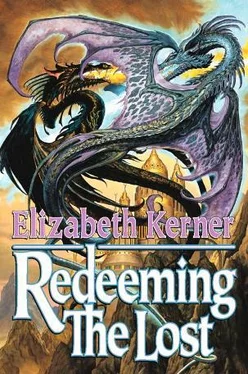

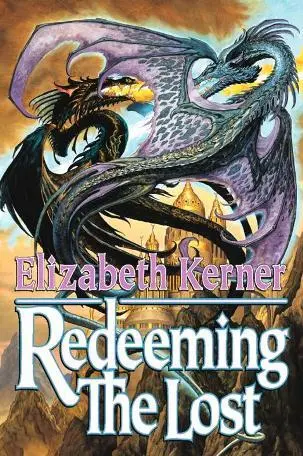

Redeeming the Lost

The third book in the Tale of Lanen Kaelarseries

Elizabeth Kerner

To

the Glory of God

and to

Martha Newman Morris Ewing

and

Sarah Alice Morris Gramley

The Marvellous Morris Girls

My mother, Martha, so desperately missed,

so dearly loved,

even if we did fight like cats and dogs

for quite a few years:

so far away in death, and as near as my mirror

where I sometimes catch a heart-stopping glimpse of you—

the ache in my heart that never forgets that you are gone,

the joy that remembers all that you were

and the indomitable warrior spirit in you

to fight for those who could not fight for themselves

My dear Aunt Sarah, whose love and affection have upheld me

in the good times, the bad times, and the dry, hard times—

whose strength and tenacity and sheer zest for life

have inspired me for many years,

whose faith in me has braced a flagging heart,

and whose truth-speaking is as rare and precious a gift

as the loving heart that prompts it—

to you, who have become my second mother

I dedicate this work

Maran Vena

Bone to iron, blood to flame— hammer, anvil, tongs, coal, water, air, fire, hammer— thus the blacksmith's soul.

At last. Nearly there. I can find the way from here, and have finally been able to release the Silent Service guide who has led me thus far. I've a feeling I should arrive on my own.

I have been ninning after my daughter these last six months, across half of Kolmar. Wretched girl. When I saw her return from the Dragon Isle with that man who was no man, when I saw my dear friend Rella stabbed the moment she stepped off the boat, I knew the time was come when I would have to face my child at last.

I have had to watch my daughter all her life from a distance. From her first step to her first kiss I have been with her half a world away and she has known nothing of me. She passed through all of childhood's more dreadful moments well enough, as far as I could tell, but when she came up against a demon-master I realised I could dwell in shadows no longer. What worse could happen, after all?

I can hear you. Already you have decided who and what I am. You think me evil, or at the very least unfeeling and unnatural. You are wrong. Listen with a mind open to wider possibilities and you may learn something.

Or perhaps there is some justice to your point of view. To be honest, I wonder about it myself in the long nights. It's not an easy question, and there's no simple answer that I can find. Life's like that—messy and mixed, heroes and cowards in the one skin. It's only in the bard's tales that good and evil are so cleanly divided.

Or in people like my daughter.

When I was young and just coming of age I was desperate to leave my home to see the wider workl—not unlike Lanen, as it happens. My mother loved me well enough, but it suited her that I should go a-wandering, for I was not to her taste as a child. My blacksmith father Heithrek loved me best of all his children and feared for me out in the world alone. I have never been a fool and understood the dangers well enough, so I waited, but each day the waiting grew harder.

Working beside my father made it at least bearable. When I first grew taller than my brothers, he laughed and put me to work in the forge. As I stayed and learned the beginnings of the craft, he would have me tend the iron in the fire, pumping away at the leather bellows until the sparks and the colour of the metal told him the iron was ready to work. I loved the fire, the warm darkness of the forge, the music of my father's hammer against the anvil, the air of mystery and creation that blew through the glowing coals as he transformed stubborn iron into well-behaved tools. The forge called me unto itself as some are called to serve the Goddess, and I answered gladly.

My father was pleased with me, but the whole idea of a female blacksmith unsettled my mother who soon asked him to dissuade me from such a strange pursuit. Heithrek did his best. He put me to drawing down the pig iron, hoping that the sheer weight of the stuff and the dullness of the work involved would put me off, but I found it a challenge and laughed with delight the first time I managed to draw down half a pig in a day without having to stop and rest.

Each of my three brothers had come to the forge to try if they were true smiths. Each one left after a short season when he found it was not in him. The eldest has become a scholar, the second a farmer, the third a shaper of wood rather than iron. My two younger and more delicate sisters, Hildr and Hervor, simply thought I was insane, and told me so when they were old enough and brave enough.

"Maran, you'll never find a man if you spend every waking moment with fire and iron," Hildr told me. "The only time the lads ever see you is when you're soot-black from the forge." She had a point, but there again, given the lads in our village, I didn't really care. It wasn't those puny lads I wanted to know more of, but the world that lay about me, enticing, so wide and so unknown. We lived in Beskin, on the edge of the Trollingwood within sight of the great East Mountain range. I grew up in the sight of mountains that reached halfway to the sky, and my heart longed for them as other maidens longed for a man.

The wanderlust grew as the years passed, as I worked beside my father and grew to my full height and strength. I had known for years that the village lads would never be a match for me m any sense. Truth be told, I was all but ready to set out into the wide world alone if there was no other way, but as luck would have it there came through our village, just in time, a mercenary looking for work. He was well-enough looking, built small but wiry, and there was that about his eyes that intrigued me—a strangeness, as of pain long borne; an otherness that spoke of distant lands; a depth in him that I could not fully understand, but that spoke of wisdom hard-gained and worth the knowing.

In any case he was obviously a man well able to keep himself. He came looking for work, and said he'd be willing to act as bodyguard—well, my father knew that I would leave soon in any case, and Jamie was a good compromise.

Jamie. The man I have loved best in all the world, though my best love has been shoddy enough. Not Lanen's father, though he should have been. Jameth of Arinoc. My Jamie.

Rella's Jamie now, damn it.

I can hardly grudge them their happiness. I left him alone to raise my daughter, and Rella has known me and been my faithful friend these twenty years gone. I should have known this would happen were they to meet.

I knew they travelled together with my daughter, some three moons past now. When I saw Jamie every day as I watched Lanen, I tried to convince myself that the long years had loosed Jamie's hold on me, but when finally I realised that Jamie and Rella were become lovers I felt a pain sharp as a knife in my breast. Part of me cries even now, like a spoiled child, but he was mine!

Aye. If he was mine, I should have been with him.

Why wasn't I with him, a neat near-family with Lanen as our daughter, and mayhap other childer for our own?

Ah. It never was meant. And it's all the fault of Marik and that Hells-be-damned Farseer.

Jamie and I had travelled together some three years, and we had been lovers much of that time. He asked me to wed him, several times, but I was young and did not want to be tied to the first man I had ever known. Fool that I was, too stupid to realise how fortune had favoured me! He taught me to defend myself, and though I never took to the blade properly, I learned enough to keep my head on my shoulders. We roamed the length and breadth of Kolmar together—oh, the tales I could tell!—until, upon a day in early autumn, in Illara during the Great Fair, I met Marik of Gundar.

Читать дальше