Rusty wadded up the paper napkin lying unused beside his plate and tossed it into the waste basket. He played with his food for a few moments, trying not to let the sound of Moms sobbing get to him. Finally, he could take it no longer and he slid away from the table, went to his room. It was going to be like that, all day, he was sure.

He turned on the record player absently, letting a stack of 45s start turning on the center post. Without knowing it, he pushed the reject button, allowing the first disc to slip down. Music had become very important to Rusty. When he had no one else around, when solitude was forced on him, he could use the music to stave off loneliness, fear. The words were pointless, the tunes vapid, but he desperately needed the sounds. Nothing more, just the sounds.

Come on over baby, Whole lot of shakin’ going on — Come on over, baby, Whole lotta shakin’ goin’ on —

The music reminded him where Dolo had gone.

He sat down heavily on the edge of the bed letting his arms hang between his legs drawing tightly at the shoulder joints. It wasn’t good to let Dolores run loose like that, particularly not tonight. Besides the rumors of Cherokee action, there was always Candle—who might still harbor enough of a grudge to want to take it out on Rusty’s sister—and Boy-O with his always handy supply of sticks. There were the girl-hungry Cougars, and the lousy influence of the Cougie Cats, many of whom had police records.

Dolores was clean so far and Rusty intended to keep her that way.

As he sat there he glanced toward the bureau and saw the picture one of the kids had taken of him and Dolo at Coney, last summer. She stood shorter than he, slim and happy in the sun with the crowded beach behind her and the cloudless sky above. And he started undressing, so he could put on some better clothes and follow Dolores to the dance.

He was going to make certain nothing happened to his sister. She had too much to live for, to let any gang of juvies louse her up.

He dressed hurriedly.

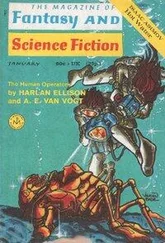

Whoever had intimidated Greaseball Bolley into letting the Cougars turn his back rooms into a club, had done a fine job. For the fat man was terrified of the hard-eyed kids who walked through his bowling alley, into the rear. He studied each one carefully, getting to know them by sight and name, against the day they decided to wreck the joint and put him down. He was more than fat; he was gigantic in that seldom-seen fantastic way that brings to mind thick dough puddings and overstuffed Morris chairs. One of the men who bowled regularly in League, Wednesday nights, who was also an avid reader of science fiction, compared Greaseball to a spaceman who had been infected with a spore that had bloated him into moon-proportions. It was a striking analogy, for Bolley’s body was not only hasty-pudding squishy, and waggled flappingly as he stumped forward, but the skin was an unhealthy yellow, pimpled and puckered and strewn with moles, pustules, explosions of flesh, that made him look like some weird diseased fruit, overripe and rotting within.

He was well-liked by everyone in the neighborhood.

But someone in the Cougars, years before Rusty had become the Prez, had decided the gang needed a clubhouse, and had decided with equal ease that the back rooms of the Paradise Bowling Alley were the site. So Greaseball Bolley had become unhappy host to the Cougars and their girls’ auxiliary. The place resounded to the stomping feet and high-flung wails of rock’n’roll, and the occasional moan of an apple who had been put down for a while.

Greaseball Bolley was unhappy about the situation, but he maintained a philosophical neutrality, for his size cut away any ideas the gang might have had about causing him trouble. He watched them and they watched him and they hung suspended in a state of alert tolerance. Enough that Bolley allowed them to use the place, as they allowed him to stay in business. It was not at all the same sort of arrangement the gang had with TomTom, who was merely terrorized. This was a grudging acceptance of strength, and a decision to permanently put off hostilities, for the good of the majority.

Greaseball was glad the spanging of pins cut off most of the Cougars’ noise.

But tonight, they were doing it up sky-blue. More than usual had tramped past the showcase with its FOR SALE sign, model pins, balls, carrying cases, shoes and other paraphernalia inside. They had all given him the eye of recognition, the two-fingered greeting and gone quietly back to the club rooms.

Greaseball never went back there. They had their own locks on the doors and they kept their house. He knew about the several bedrooms, about the girls and boys who stayed overnight, about the slashings and the narcotics, but his fear of gang reprisal was greater than that of the police, so he kept his mouth shut and the Cougars made sure they did nothing overt to attract the attention of The Men. It had been that way for a long time now and the days seemed endlessly plodding in danger to Greaseball. But he did nothing to stop them. Far back, before the Cougars, there had been some trouble with a waitress, and a broken bottle, and a long term inside gray walls. So Greaseball Bolley did nothing, but watch and let them sink into his mind’s eye. And if someday the balance shifted he would take as many with him as he could. But till then…

He was well-liked by everyone in the neighborhood.

Rusty passed Greaseball Bolley with all the cool aplomb of the days when he had been Prez. He kept his eyes front and his step assured as he walked past the gigantic heap of doughy flesh. But for the first time since he had met the fat man, on taking over the Cougars, Greaseball spoke to Rusty.

“ ’Ey. You, Santori. C’mere.”

Rusty stopped and pivoted slowly. His eyes met those of the fat man and for a minute he had trouble deciding what color they were; so deeply buried in caverns of oozing flesh they seemed to be two raisins thumbed into a paste. “The name’s Santoro, not Santori,” Rusty stated flatly, starting to go.

“ ’Ey. When I call you, kid, you come, y’hear?”

Rusty walked back to where the hump of Bolley leaned over the showcase. Down on the alleys only two or three people bowled—none of whom Rusty recalled having ever seen in the place before—and it was apparent the rumors of Cherokee trouble had hit the neighborhood hard enough to keep regulars away from the place.

Rusty realized Greaseball was scared. For the first time since he had known him the fat man was afraid of something. Rusty walked over, close enough to smell the odor of garlic and no bathing, and his nostrils quivered. Then he stopped, drew on his cigarette and waited for the fat man to speak.

“You—uh—you hear ’bout trouble, t’night?”

Rusty let his eyes slide tightly closed. The smoke from the cigarette spiraled up past his face and he liked the momentary warmth of it. Cool, that was the angle, play it cool. It goes further, it slides easier.

“Trouble? Like what trouble, man?”

Greaseball felt fire flame in his huge belly. He would not tolerate these kids stooging it out on him. He reached across with one side-of-beef hand and grabbed Rusty about his collar. The sports jacket Rusty wore wrinkled up as the fat man dragged the boy tight to the counter. Rusty reached up to try and jab free, but the hand was a bracelet of soft, spongy, but terribly invulnerable flesh. He was held fast and his breath was jagged as he worked his neck in the grip.

“Lemme go! Goddamn ya, lemme go, ya sleazy crumbum!”

The fat man’s other hand came about lazily, almost floatingly (he knew his own strength to the smallest fraction) and landed with a heavy plop on Rusty’s face. The boy’s eyes glazed over and he staggered in Greaseball’s grip.

Читать дальше