INTRODUCTION:

UNNECESSARY WORDS

There’s really no point to writing an introduction to a novel. A book of short stories, sure, okay. A collection of essays, definitely. A scholarly tome, naturally. But what the hell should one have to say about an entertainment, a fiction, a novel? Nothing. It should speak for itself.

And I intend to let it.

Even so, I’d like to make one brief statement about the book. Bear with me; I won’t be long.

There’s a story told about Hemingway—I don’t know if it’s true or not, but if it isn’t, it ought to be. The story goes that he was either on his way to France or on his way back from France, one or the other, I don’t recall the specifics of the anecdote that well. He was on shipboard, and he had with him his first novel. Not The Sun Also Rises; the one he wrote before that “first novel” that made him a literary catchword almost overnight.

Yes, the story goes, Hemingway had written a book before The Sun Also Rises , and there he was aboard ship, steaming either here or there; and he was at the rail, leaning over, thinking, and then he took the boxed manuscript of the book… and threw it into the ocean.

Apparently on the theory that no one should ever read a writer’s first novel.

Which would mean—were all writers to subscribe to that theory—we’d never have had One Hundred Dollar Misunderstanding or The Catcher in the Rye or From Here to Eternity or The Seven Who Fled or The Painted Bird or Gone With the Wind or...

Well, you get the idea.

I don’t know whether to argue with the theory or not, but I suppose I’m lobbying against it by permitting (nay, encouraging) this reprint of my first novel, Web of the City. It was my first book, written under mostly awful personal circumstances, and I’m rather fond of it. I’ve re-read it this last week, just to find out how amateurish and inept it is, and I find it still holds the interest. I even gave it to a couple of nasty types who profess to being my friends when they aren’t sticking it in my back, and even they say it’s worth preserving.

So the book is alive once more.

The time about which it speaks is gone—the early fifties; and the place it talks about has changed somewhat—Brooklyn, the slums. But it has a kind of innocent verve about it that commends it to your attention. I hope, of course, that you’ll agree with me.

In case you might wonder, I began writing it around the tail end of 1956 and the first three months of 1957. I was drafted in March of 1957 and wrote the bulk of the book while undergoing the horrors of Ranger basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia. After a full day, from damned near dawn till well after dusk, marching, drilling, crawling on my belly across infiltration courses, jumping off static-line towers, learning to carve people up with bayonets and break their bodies with judo and other unpleasant martial arts, our company would be fed and then hustled into a barracks, where the crazed killers who were my fellow troopers would clean their weapons, spit-shine their boots, and then collapse across their bunks to sleep the sleep of the tormented. I, on the other hand, would take a wooden plank, my Olympia typewriter, and my box of manuscript and blank paper, and would go into the head (that’s the toilet to you civilized folks), place the board across my lap as I sat on one of the potties, and I would write this book.

After the first couple of fist fights, they stopped complaining about the noise and let me alone. But Sgt. Jacobowski called me, in his dragon’s voice, “The Author.” The way he pronounced it, it always came out sounding like The Aw-ter.

The editor who bought the book originally, who took the first chance on me as a novelist, was a wonderful guy named Walter Fultz. He was the editor at Lion Books, a minor paperback house that gave a lot of newcomers a break. Walter is dead now, tragically, before his time, but I think he would have liked to’ve seen how long-lived this book has become, and how the kid he gave a break has come along.

Lion Books went out of business before they could release Web of the City, and the backlog of titles was sold here and there. Pyramid Books then bought the manuscript.

It was almost a year later, in 1958, while I was serving out my sentence as the most-often-demoted PFC in the history of the United States Army, at Fort Knox, Kentucky, when this book finally hit print. I was writing for the Fort Knox newspaper, and getting boxes of review paperbacks for a column I was doing, when the August shipment of Pyramid titles came in. I opened the box, flipped through the various products therein, and almost had a coronary when I held in my hands, for the first time in my life, a book with my name on the cover.

Except, the book was titled Rumble.

Nonetheless, it was an experience that comes only once in a writer’s life, the first book, and I was the tallest walkin’ Private in the Army that week.

Maybe I should have taken sides with old Ernie, dumping this book in the Pacific as he dumped that first novel in the Atlantic; but I cannot forget the hot August afternoon in Kentucky during which I realized my life’s dream and became, for the first time, an author.

And even if Web of the City isn’t War and Peace, you just can’t kill something you’ve loved as much as I love this book.

So read on and, with a little compassion on your part, you’ll be kind to the memory of the punk kid who wrote it.

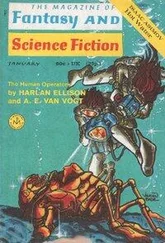

HARLAN ELLISON

rusty santoro

the cougars

The city lay cool and dim beneath a vaulting sky of high-scudding gray clouds. A gray shroud that covered the corpses of buildings, stiff in brick-and-steel rigor mortis, pale in their eternity of sooty death.

The heat of the afternoon had slowly passed away, the trembling waves of warmth disappearing like wraiths to be replaced by mugginess and unrest; the sweat had gone back into the pores, the cats back into the alleys, the wineheads back into the bars, the amateurs back to their pads.

It was evening, and evening was free time, and free time was the time to go! Rusty was abroad in the night.

His name was Rusty, but it wasn’t really Rusty, and he had cut the umbilicus that bound him to the gang. A half hour before he had faced the gang and snarled, “I told ya a couple months ago I was through, that I was split with the Cougars, an’ ya been buggin’ me ever since to come back. Now you better know what I’m sayin’—’specially you, Candle—that I’m done.

“That’s my answer. Now I’m splittin’ and I don’t want no trouble.”

That had been the speech, and those had been the emotions, and that was what had started it, what had set the spider to weaving. The spider was a city, gray and observant and jealous once in a while, though deep inside it didn’t really care at all. But the black widow cannot stop weaving, and the city cannot stop weaving. Alike in temperament, they feast on their spawn.

It was good to get away from them. Rusty felt the sweat that had come to live on his spine trickle down like a small bug. He had made his peace with them, and he was free of the gang. That was it. He had it knocked now. He’d built a big sin, but it was a broken bit now. The gang was there, and he was here.

He was no longer Prez of the Cougars, and the road was starting to open up. He’d be able to walk past the fuzz on the corner, and not have the bluecoat stare at him like he was hot or something. He was out and gliding.

Читать дальше