“You still staying at Margaret’s?”

“That’s why I called.” Her sister Margaret had a small one-bedroom apartment in Central Square in Cambridge. Sarah had to be sleeping on the couch, and it had to be an annoyance to her sister. In the best of times they had a contentious relationship. “You’re going to be getting a call today from a company, a real estate company. They’re going to need you to send them a couple of my 1099s. Proof of income.” As one of the two original investors and an officer of the company, Sarah was given a salary, which wasn’t a lot of money.

“What’s this about?”

“I can’t stay at Margaret’s any longer. We’re driving each other crazy.”

“Come on home, sweetie.”

He looked back at Sal, bent over the tumblers, removing the crust. He wondered if his voice carried. He hadn’t told anyone at work about Sarah moving out. It was none of his employees’ business; he liked to keep work and home separate.

“I’m renting an apartment in Cambridge.”

“Come on, Sarah, that’s ridiculous. Come home and let’s talk. We can sleep in separate bedrooms, if you want.”

“I’ve already signed the lease. I gave them a deposit.”

“You can stop the check. You’re a Realtor — you know people in the business.”

“Tanner, I’ve gotta go,” she said, and she was gone.

One night a month or so ago he’d unlocked the front door, sniffed the air, and smelled nothing besides the faint odors of the lemon furniture oil and the Murphy’s Oil Soap Sarah used on the wooden floors. The slightly musty smell of the old house. But the strange thing was what he didn’t smell. No food cooking. No dinner. The house was still and quiet. The kitchen lights were off. Maybe she’d ordered out and it hadn’t arrived yet.

“Sarah?” he’d called out.

No answer.

“Sarah, you home?”

Nothing. She wasn’t home. Strange. He looked around a little longer, bewildered, until he was sure she was gone.

He knew why.

They’d had a fight, sort of, the night before. “Sort of” because Tanner didn’t actually fight; he was incapable of it. His parents had had a turbulent relationship, fought constantly and loudly. When Tanner was little he’d run upstairs to his bedroom and put a pillow over his head so he wouldn’t have to hear it. He vowed never to be like them. He didn’t argue or fight with people, never had, didn’t know how. He let his aggression out in sports, but that was it. He avoided conflict whenever possible.

Whereas Sarah tended to be volatile. She was a highly flammable substance. She and her sisters argued all the time. Occasionally she’d try to goad him into an argument, but it was like trying to strike a damp match. There were no sparks. He wasn’t combustible. He had dozens of prefab anger-dampening responses: Well, then I guess we just disagree. You may be right. I get why you feel that way, and I’m sorry.

So they’d had a disagreement the night before, a semi-argument. She wanted kids, and he wasn’t ready. This was an argument that was probably playing out in ten million other homes around the world at any moment. She liked to use a code word, a euphemism for having a kid: “expansion.” As in: “When are we going to talk about expansion?” Tanner would explain to her that he wanted to get Tanner Roast stabilized and on a steady path before he committed to starting a family.

But Sarah’s biological clock was ticking. She was thirty-three, and she wanted to have several kids, and if they didn’t do it soon it probably wouldn’t happen. Whereas he kept insisting he needed to know he could keep the company solvent without having to lay anyone off. Sarah said that was his way of avoiding committing to the marriage, to her. And so on.

She’d gone to bed angry.

The night she didn’t come home, he called her.

“Michael,” she said when she picked up. Being demoted from “Tanner” to “Michael” was already disconcerting.

“What’s going on?” he said. “I don’t understand.”

“I’m staying at Margaret’s.”

“Why?”

A long sigh. “So what is it with you? Is the company, like, your child? Is that it? Is that why you don’t want to have a baby with me?”

“I never said I don’t want to have kids. Sarah—”

“No, you said you’re not ready. You’re never ready.”

“I just want to get the company on its feet. In the black. Right now it feels like it’s going down the tubes.” Why did she not understand this? “I want kids. Come on back, we’ll try.”

Is the company your child? Actually, Tanner Roast was like a family. And he was the dad.

Now he wandered back to the long table and the tumblers of coffee.

“Everything okay?” Sal asked.

“Absolutely,” Tanner said. “So what do we have here?”

It wasn’t until after the morning videoconference that Will was able to return to the matter of the missing laptop. He had a stack of phone calls to return, most important being a major donor who wanted to talk about an aviation bill. That was someone whose call you returned quickly.

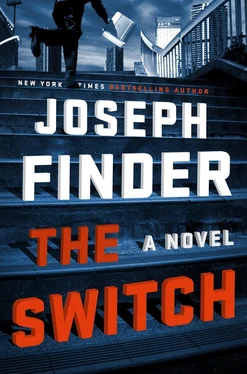

He got up and shut his office door. The MacBook Air was sitting on the corner of his desk, gleaming, waiting, a reproof. He pulled it in front of him and opened the lid. In the middle of the screen was a little oval containing a headshot of some guy, obviously the owner, and the name “Michael Tanner.” Below it was a space that said “Enter Password.”

He entered the word “password” and hit Return — some people who couldn’t be bothered to memorize a password tried to be clever. In response the little icon shook. Uh-uh.

He entered “1234” and hit Return and the screen shook no again. He tried “12345678,” and still no.

He tried “99999” and got the shake.

He tried a couple more common default passwords — “987654” and “1111111” — and each time got the shake.

There had to be a way to hack into the laptop without the password, but he didn’t know it. And maybe it wouldn’t be necessary. The computer belonged to someone named Michael Tanner. How many Michael Tanners could there be in the United States?

He swiveled his chair toward the keyboard tray and opened a new browser window. In WhitePages.com he typed “Michael Tanner” and hit Return and found 710 matches around the country.

So much for making a few phone calls to track down the owner. Not remotely feasible.

So there was no choice: somehow he had to hack into the MacBook. Find out whose it was and ask him to return Susan’s.

That called for someone with computer chops far beyond his. They shared an IT specialist with a couple of other senators. The guy was good enough, so far as Will could tell, but he wasn’t going to ask him to hack into someone’s laptop that wasn’t the senator’s. And if they did find some way to remotely access her laptop, that could be deadly. These guys weren’t priests or psychiatrists. They weren’t bound by an oath of confidentiality.

No, he needed a computer guy who could be trusted, and that meant finding someone — anyone — who knew nothing about the circumstances, who could be trusted because he was ignorant. Tell him what happened, how the laptop ended up in the senator’s hands, and he’d be intrigued and might tell someone.

But if Will Abbott brought in a MacBook Air and sheepishly admitted he’d forgotten the password... well, that was benign enough, right? It couldn’t be terribly complicated to reset a computer. He Googled computer repair places and found a place that looked reputable on C Street on Capitol Hill. He called and waited through the prompts and then pressed 5 to talk to a “specialist.”

Читать дальше