THAT NIGHT I WATCHED the ten o'clock news before going to bed. I looked disinterestedly at some footage about a State Police traffic check, taken outside Jeanerette, until I saw Clete Purcel on the screen, showing his license to a trooper, then being escorted to a cruiser.

Back in the stew pot, I thought, probably for violating the spirit of his restricted permit, which allowed him to drive only for business purposes.

But that was Clete, always in trouble, always out of sync with the rest of the world. I knew the trooper was doing his job and Clete had earned his night in the bag, but I had to pause and wonder at the illusionary cell glue that made us feel safe about the society we lived in.

Archer Terrebonne, who would murder in order to break unions, financed a movie about the travail and privation of plantation workers in the 1940s. The production company helped launder money from the sale of China white. The FBI protected sociopaths like Harpo Scruggs and let his victims pay the tab. Harpo Scruggs worked for the state of Louisiana and murdered prisoners in Angola. The vested interest of government and criminals and respectable people was often the same.

In my scrapbook I had an inscribed photograph that Clete had given me when we were both in uniform at NOPD. It had been taken by an Associated Press photographer at night on a Swift Boat in Vietnam, somewhere up the Mekong, in the middle of a firefight. Clete was behind a pair of twin fifties, wearing a steel pot and a flack vest with no shirt, his youthful face lighted by a flare, tracers floating away into the darkness like segmented neon.

I could almost hear him singing, "I got a freaky old lady name of Cocaine Katie."

I thought about calling the jail in Jeanerette, but I knew he would be back on the street in the morning, nothing learned, deeper in debt to a bondsman, trying to sweep the snakes and spiders back in their baskets with vodka and grapefruit juice.

He made me think of my father, Aldous, whom people in the oil field always called Big Al Robicheaux, as though it were one name. It took seven Lafayette cops in Anders Pool Room to put him in jail. The fight wrecked the pool room from one end to the other. They hit him with batons, broke chairs on his shoulders and back, and finally got his mother to talk him into submission so they didn't have to kill him.

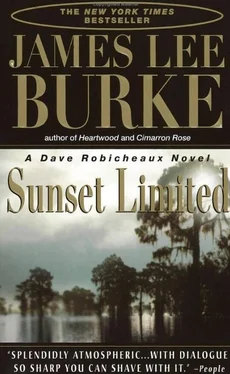

But jails and poverty and baton-swinging cops never broke his spirit. It took my mother's infidelities to do that. The Amtrak still ran on the old Southern Pacific roadbed that had carried my mother out to Hollywood in 1946, made up of the same cars from the original Sunset Limited she had ridden in, perhaps with the same desert scenes painted on the walls. Sometimes when I would see the Amtrak crossing through winter fields of burned cane stubble, I would wonder what my mother felt when she stepped down on the platform at Union Station in Los Angeles, her pillbox hat slanted on her head, her purse clenched in her small hand. Did she believe the shining air and the orange trees and the blue outline of the San Gabriel Mountains had been created especially for her, to be discovered in exactly this moment, in a train station that echoed like a cathedral? Did she walk into the green roll of the Pacific and feel the water balloon her dress out from her thighs and fill her with a sexual pleasure that no man ever gave her?

What's the point?

Hitler and George Orwell already said it. History books are written by and about the Terrebonnes of this world, not jarheads up the Mekong or people who die in oil-well blowouts or illiterate Cajun women who believe the locomotive whistle on the Sunset Limited calls for them.

ADRIEN GLAZIER CALLED Monday morning from New Orleans.

"You remember a hooker by the name of Ruby Gravano?" she asked.

"She gave us the first solid lead on Harpo Scruggs. She had an autistic son named Nick," I said.

"That's the one."

"We put her on the train to Houston. She was getting out of the life."

"Her career change must have been short-lived. She was selling out of her pants again Saturday night. We think she tricked the shooter in the Ricky Scar gig. Unlucky girl."

"What happened?"

"Her pimp is a peckerwood named Beeler Grissum. Know him?"

"Yeah, he's a Murphy artist who works the Quarter and Airline Highway."

"He worked the wrong dude this time. He and Ruby Gravano tried to set up the outraged-boyfriend skit. The john broke Grissum's neck with a karate kick. Ruby told NOPD she'd seen the John a week or so ago with a dwarf. So they thought maybe he was the shooter on the Scarlotti hit and they called us."

"Who's the john?"

"All she could say was he has a Canadian passport, blond or gold hair, and a green-and-red scorpion tattooed on his left shoulder. We'll send the composite through, but it looks generic-egg-shaped head, elongated eyes, sideburns, fedora with a feather in it. I'm starting to think all these guys had the same mother."

"Where's Ruby now?"

"At Charity."

"What'd he do to her?"

"You don't want to know."

A FEW MINUTES LATER the composite came through the fax machine and I took it out to Cisco Flynn's place on the Loreauville road. When no one answered the door, I walked around the side of the house toward the patio in back. I could hear the voices of both Cisco and Billy Holtzner, arguing furiously.

"You got a taste, then you put your whole face in the trough. Now you swim for the shore with the rats," Holtzner said.

"You ripped them off, Billy. I'm not taking the fall," Cisco said.

"This fine house, this fantasy you got about being a southern gentleman, where you think it all comes from? You made your money off of me."

"So I'm supposed to give it back because you burned the wrong guys? That's the way they do business in the garment district?"

Then I heard their feet shuffling, a piece of iron furniture scrape on brick, a slap, like a hand hitting a body, and Cisco's voice saying, "Don't embarrass yourself on top of it, Billy."

A moment later Holtzner came around the back corner of the house, walking fast, his face heated, his stare twisted with his own thoughts. I held up the composite drawing in front of him.

"You know this guy?" I asked.

"No."

"The FBI thinks he's a contract assassin."

Holtzner's eyes were dilated, red along the rims, his skin filmed with an iridescent shine, a faint body odor emanating from his clothes, like a man who feels he's about to slide down a razor blade.

"So you bring it out to Cisco Flynn's house? Who you think is the target for these assholes?" he said.

"I see. You are."

"You got me made for a coward. It doesn't bother me. I don't care what happens to me anymore. But my daughter never harmed anybody except herself. All pinhead back there has to do is mortgage his house and we can make a down payment on our debt. I'm talking about my daughter's life here. Am I getting through to you?"

"You have a very unpleasant way of talking to people, Mr. Holtzner," I said.

"Go fuck yourself," he said, and walked across the lawn to his automobile, which he had parked under a shade tree.

I followed him and propped both my hands on the edge of his open window just as he turned the ignition.

He looked up abruptly into my face. His leaded eyelids made me think of a frog's.

"Your daughter's been threatened? Explicitly?" I said.

" Explicitly ? I can always spot a thinker," he said. He dropped the car into reverse and spun two black tracks across the grass to the driveway.

I went back up on the gallery and knocked again. But Megan came to the door instead of Cisco. She stepped outside without inviting me in, a brown paper bag in her hand.

"I'm returning your pistol," she said.

Читать дальше