I ran even faster. It had been years since I'd run more than a couple of hundred yards and my lungs were already wheezing and gasping like a fractured bellows in a blacksmith's shop. But I ran as hard as I could. I cannoned into trees, I tripped over roots, fell into gullies, had my face whipped time and again by low-spreading branches, but above all I cannoned into those damned trees, I stretched my arms before me but it did no good, I ran into them all the same. I picked up a broken branch I'd tripped over and held it in front of me but no matter how I pointed h the trees always seemed to come at me from another direction. I hit every tree in the Island of Torbay. I felt the way a bowling ball must feel after a hard season in a bowling alley, the only difference, and a notable one, being that whereas the ball knocked the skittles down, the trees knocked me down. Once, twice, three times I heard the sound of the helicopter engine disappearing away to the east, and the third time I was sure be was gone for good. But each time it came back. The sky was lightening to the east now, but still I couldn't see the helicopter: for the pilot, everything below would still be as black as night.

The ground gave way beneath my feet and I fell. I braced myself, arms outstretched, for the impact as I struck the other side of the gully. But my reaching hands found nothing. No impact. I kept on falling, rolling and twisting down a heathery slope, and for the first time that night I would have welcomed the appearance of a pine tree, any kind of tree, to stop my progress. I don't know how many trees there were on that slope, I missed the lot. If it was a gully, it was the biggest gully on the Island of Torbay. But it wasn't a gully at all, it was the end of Torbay, I rolled and bumped over a sudden horizontal grassy bank and landed on my back in soft wet sand. Even white I was whooping and gasping and trying to get my knocked-out breath back into my lungs I still had time to appreciate the fortunate fact that kindly providence arid a few million years had changed the jagged rocks that must once have fringed that shore into a nice soft yielding sandy beach.

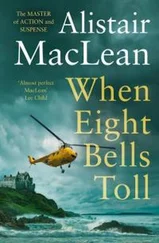

I got to my feet. This was the place, all right. There was only one such sandy bay, I'd been told, in the east of the Isle of Torbay and there was now enough light for me to see that this was indeed just that, though a lot smaller than it appeared on the chart. The helicopter was coming in again from the east, not, as far as I could judge, more than three or four hundred feet up. I ran half-way down to the water's edge, pulled a hand flare from my pocket, slid away the waterproof covering and tore off the ignition strip. It flared into life at once, a dazzling blue-white magnesium light so blinding that I had to clap my free hand over my eyes. It lasted for only thirty seconds, but that was enough. Even as it fizzled and sputtered its acrid and nostril-wrinkling way to extinction the helicopter was almost directly over-head. Two vertically-downward pointing searchlights, mounted fore and aft on the helicopter, switched on simultaneously, interlocking pools of brilliance on the pale white sand. Twenty seconds later the skids sank into the soft sand, the rackety clangour of the motor died away and the blades idled slowly to a stop. I'd never been in a helicopter in my life but I'd seen plenty: in the half-darkness this looked like the biggest one I'd ever seen.

The right-hand door opened and a torch shone in my face as I approached. A voice, Welsh as the Rhondda Valley, said: "Morning. You Calvert?"

"Me. Can I come aboard?"

"How do I know you're Calvert?"

"I'm telling you. Don't come the hard man, laddie. You've no authority to make an identification check."

"Have you no proof? No papers?"

"Have you no sense? Haven't you enough sense to know that there are some people who never carry any means of identification? Do you think I just happened to be standing here, five miles from nowhere, and that I just happened to be carrying flares in my pocket? You want to join the ranks of the unemployed before sunset?" A very auspicious beginning to our association.

"I was told to be careful." He was as worried and upset as a cat snoozing on a sun-warmed wall. Still a marked lack of cordiality. "Lieutenant Scott Williams, Fleet Air Arm. Takes an admiral to sack me. Step up."

I stepped up, closed the door and sat. He didn't offer to shake hands. He flicked on an overhead light and said: "What the hell's happened to your face?"

"What's the matter with my face?"

"Blood. Hundreds of little scratches."

"Pine needles." I told him what had happened. "Why a machine this size? You could ferry a battalion in this one."

"Fourteen men, to be precise. I do lots of crazy things, Calvert, but I don't fly itsy-bitsy two-bit choppers in this kind of weather. Be blown out of the sky. With only two of us, the long-range tanks are full."

"You can fly all day?"

"More or less. Depends how fast we go. What do you want from me?"

"Civility, for a start. Or don't you like early morning rising?"

"I’m an Air-Sea Rescue pilot, Calvert. This is the only machine on the base big enough to go out looking in this kind of weather. And I should be out looking, not out on some cloak-and-dagger joy-ride. I don't care how important it is, there's people maybe clinging to a life-raft fifty miles out in the Atlantic. That's my job. But I've got my orders. What do you want?"

"The Moray Rose."

"You heard? Yes, that's her."

"She doesn't exist. She never has existed."

"What are you talking about? The news broadcasts — "

"I'll tell you as much as you need to know, Lieutenant. It's essential that I be able to search this area without arousing suspicion. The only way that can be done is by inventing an ironclad reason. The foundering Moray Rose is that reason. So we tell the tale."

"Phoney?"

"Phoney."

"You can fix it?" he said slowly. "You can fix a news broadcast?"

"Yes."

"Maybe you could get me fired at that." He smiled for the first time. "Sorry, sir. Lieutenant Williams Scotty to you — is now his normal cheerful willing self. What's on?"

"Know the coast-lines and islands of this area well?"

"From the air?"

"Yes."

"I've been here twenty months now. Air-Sea Rescue and in between army and navy exercises and hunting for lost climbers. Most of my work is with the Marine Commandos. I know this area at least as well as any man alive."

"I'm looking for a place where a man could hide a boat. A fairly big boat. Forty feet — maybe fifty. Might be in a big boathouse, might be under over-hanging trees up some creek, might even be in some tiny secluded harbour normally invisible from the sea. Between Islay and Skye."

"Well, now, is that all. Have you any idea how many hundreds of miles of coastline there is in that lot, taking in all the islands? Maybe thousands? How long do I have for this job? A month?"

"By sunset to-day. Now, wait. We can cut out all centres of population, and by that I mean anything with more than two or three houses together. We can cut out known fishing grounds. We can cut out regular steamship routes. Does that help?"

"A lot. What are we really looking for?"

"I've told you."

"Okay, okay, so mine is not to reason why. Any idea where you'd like to start, any ideas for limiting the search?"

"Let's go due east to the mainland. Twenty miles up the coast, then twenty south. Then we'll try Torbay Sound and the Isle of Torbay. Then the islands farther west and north."

"Torbay Sound has a steamer service."

"Sorry, I should have said a daily service. Torbay has a bi-weekly service."

"Fasten your seat-belt and get on those earphones. We're going to get thrown around quite a bit to-day. I hope you're a good sailor."

"And the earphones?" They were the biggest I'd ever seen, four inches wide with inch-thick linings of what looked like sorbo rubber. A spring loaded swing microphone was attached to the headband.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу