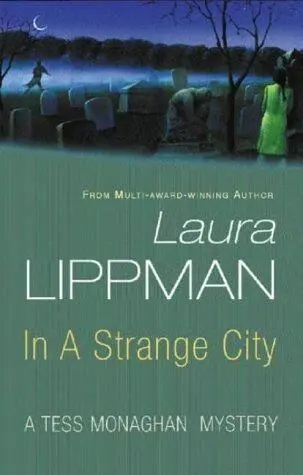

Laura Lippman

In A Strange City

The sixth book in the Tess Monaghan series, 2001

In Memory of Dulcie (1993-2000) and Spike the Elder (1984-1997)

And with gratitude for Spike Jr., who makes the unbearable bearable

Lo! Death has reared himself a throne

In a strange city, lying alone

Far down among the dim West,

Where the good and the bad and the worst and the best Have gone to their eternal rest.

Edgar Allan Poe, “The City in the Sea”

He begins on January 1, always January 1, playing with his body’s schedule until he is increasingly nocturnal, staying up until dawn. Sometimes he finds an all-night diner, although he has learned not to rely on the crutch of caffeine to get through this. He takes a book, sips water or juice, eats plain things: a soft-boiled egg, whole wheat toast, rice pudding. It takes almost three weeks to prepare, another three weeks to recover, but preparation is crucial. He learned that the first year.

The first year. How long has it been now? He doesn’t want to count. How naïve he was, how unthinking. How young, in other words. He did not stop to consider the enormity of the commitment he was making, how quickly it would begin to feel like a prison sentence. He did not know how the cold settled in one’s bones for days. He did not realize the cape would rip and unravel and he would have to learn to repair it, for he could not risk taking it to the seamstress at the dry cleaners. He did not work out the logistics of buying roses at this time of year, how he would have to move from florist to florist and buy more than he needed, lest someone put it together.

The cognac was easy, at least. He bought it by the case, at a 10 percent discount, at Beltway Liquors.

What’s the difference between a ritual and a routine? It’s a question he asks himself almost every day. Are rituals better than routines, more elevated? Or do rituals invariably slide into routine, until we forget why we started and why we continue? Another good question, but he’s afraid pondering the answer will only tempt him to sleep, and he is determined to see the sun rise today. Once upon a midnight dreary… ah, but such allusions are unworthy, the sort of obvious unthinking wordplay one expects from the newspaper hacks who write about him. Even in print, they cannot capture him.

He would not say it out loud-for one thing, he has no one to whom to say it-but he has begun to feel a kinship with Santa Claus. Who knows, Saint Nick was probably real once. A man decides to put on a red suit, visit a few houses in his village, and leave gifts behind. The first year, it was a lark. The next year, it was an obligation. And then the next, and the next, until he could never stop.

But in that case, the tradition outgrew the man, so others had to step forward and preserve it. He cannot count on this happening here. He had been chosen, and soon he must choose.

The room is cold. The landlord turns the heat down at night. He stirs the embers in the dying fire, tucks a stadium blanket around his legs. He knows this blue-plaid blanket. It was his father’s; it came in a plastic bag that zipped and had been used exclusively for its named purpose. He remembers being beneath it at Memorial Stadium, watching the Colts, drinking hot chocolate from an old-fashioned thermos, the very thermos that now sits on his desk, dented here and there and full of herbal tea, not chocolate, but still going strong.

“He takes such good care of his things,” he overheard his mother say once, admiringly, to a friend, and he was so unused to this prideful tone in her voice that he determined he would always be known for this. He takes such good care of his things. He still has his train set, his Lincoln Logs, a silver bullet presented to him by Clayton Moore, even the blue Currier amp; Ives plates from his mother’s kitchen. The Museum of Me, that’s how he thinks of his place here in North Baltimore, where every item has a history. It’s a charming image: his apartment behind Plexiglas, hushed visitors trooping through, as if this were Monticello or Mount Vernon. Ladies and gentlemen, this thermos was present for the Colts’ loss to the New York Jets, as was this plaid blanket.

Actually he remembers the blanket better than the games; it was scratchier then, for it was still new, and they could never fold it so it went back into the case. Mother always had to do that for them when they got home. He wonders what happened to the case, how the blanket survived when the case did not.

But it’s the same thing with the body, is it not? The case cannot survive, yet it may leave something behind. He has no children, no money to speak of, and his things-his books, his various collections-will go to his alma mater, déclassé as College Park might be. His only legacy is this secret, and he can give it to only one person. Yet it seems increasingly possible that no one will have it. No one wants it.

There would have been more possibilities a generation ago, he’s sure of that. More men like himself from whom to pick. These days, he does not meet many people, like himself or otherwise, and this saddens him. There was one, encountered by chance in the all-night diner on Twenty-ninth Street -but no, that young man was clearly not what he seemed. He finds himself loitering in used-book shops and antiques stores, where young women go into ecstasies over old green-handled potato mashers and pastry cutters. He feels as if he is not much different. An odd tool, prized for its quaint, decorative quality but of no utility.

He did not think people could go out of style, but apparently he has. The vocabulary used to describe a man like himself, once full of solemn dignity, has been reduced to the simperingly ironic. Bachelor. Sometimes, meeting a new person, he pretends to be a widower. If the new acquaintance is a woman, her face lights up in a way she may not realize. A widower! It means he was capable of living with someone, at least once. But that was the one thing of which he was never capable, no more than he could end a sentence with a preposition. He needs solitude, craves it the way some people yearn for food, or sex, or drink. Is it so freakish to want to live alone?

His head tips forward from its own weight; he jerks it back and fixes his gaze on the view. A rim of light is on the horizon. No clouds, which means it will be even colder today than it was yesterday, and colder still tomorrow. The appointed night has never been less than freezing; he has not once caught a break with the weather, and there have been times-sleet sharp as knives, streets impassable with snow-when he wondered if he would make it at all. This year promises to be no different. Why January? he thinks, not for the first time. Why not October, the day he died? The weather is so much more reliable then.

The ghostly glow in the east expands; the sky’s hem is pink. Ten more minutes, and he will let himself sleep. Perhaps if he recited something. He remembers a game he and P played, where someone picked a single word-dream, night, midnight, soul-and then recited in turn, until their knowledge was exhausted. P had always won, but P is long gone. He has to play by himself.

Let’s see, “Night.” The night-tho‘ clear-shall frown. “Soul.” There is a two-fold silence-sea and shore-body and soul. One dwells in lonely places. “Heaven.” Thank Heaven! the crisis-/The danger is past,/And the lingering illness is over at last-/And the fever called “living”/Is conquered at last. “Dream.” Is all that we see or seem/But a dream within a dream?

Читать дальше