“Impossible to say. The working boys – you know what I mean by ‘working’ – only stay here when they’re sick or between hawks. If he’s scared about something he’ll go to ground and it could be six months before we see him again. If ever. You live in the city?”

“I’m from the Coast. I’m renting in the East Village.”

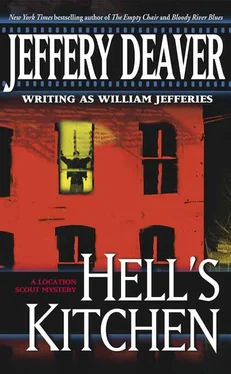

“The Village? Shit, Hell’s Kitchen sleaze beats their sleaze hands down. So, give me your number. And if our wandering waif comes home I’ll let you know.”

Pellam wished he hadn’t thought of her as a peasant. He couldn’t dislodge the thought. Peasants were earthy, peasants were lusty. Especially red-haired peasants with freckles. He found himself calculating that the last time he’d slept with a woman they’d wakened in the middle of the night to the sound of winds pelting the side of his Winnebago with wet snow. Today the temperature had reached 99.

He pushed those thoughts aside though they didn’t go as far away as he wanted them to.

There was a dense pause. Pellam asked impulsively, “Listen, you want to get some coffee?”

She reached for her nose, to adjust the glasses, then changed her mind and took them off. She gave an embarrassed laugh and readjusted the glasses again. Then she gave a tug at the hem of her sweatshirt. Pellam had seen the gesture before and sensed that a handful of insecurities – probably about her weight and clothes – was flooding into her thoughts.

Something in him warned against saying, “You look fine,” and he chose something more innocuous. “Gotta warn you, though. I don’t do espresso.”

She brushed her hair into place with thick fingers. Laughed.

He continued, “None of that Starbucks, Yuppie, French-roast crap. It’s American or nothing.”

“Isn’t it Colombian?”

“Well, Latin American.”

Carol joked, “You probably like it in unrecyclable Styrofoam too.”

“I’d spray it out of an aerosol can if they made it that way.”

“There’s a place up the street,” she said. “A little deli I go to.”

“Let’s do it.”

Carol called, “Be back in fifteen.”

A response in Spanish, which Pellam couldn’t make out, came from the back room.

He opened the door for her. She brushed against him on the way out. Had she done so on purpose?

Eight months, Pellam found himself thinking. Then told himself to stop.

They sat on the curb near Ettie’s building. At their feet were two blue coffee cartons depicting dancing Greeks. Carol wiped her forehead with the souvenir Cambridge cotton and asked, “Who’s he?” Pellam turned and looked where Carol was pointing.

Ismail and his tricolor windbreaker had mysteriously returned. He now played in the cab of the bulldozer that had been leveling the lot beside Ettie’s building. “Yo, my man, careful up there,” Pellam called. He explained to Carol about Ismail, his mother and sister.

“The shelter in the school? It’s one of the better ones,” Carol said. “They’ll probably get them into an SRO in a month or so. Single room occupancy – a residence hotel. At least if they’re lucky.”

“So, you know the neighborhood pretty well?” he asked.

“Cut my social work teeth here.”

“You’d know the good stuff then. The stuff that we touristas never find out.”

“Try me.” Carol glanced at the tooling on Pellam’s battered black Nokona cowboy boots.

“The gangs,” he said.

“The crews? Sure, I know about them. But I don’t deal much with them. See, if a kid’s in a set he’s gonna get all the support he needs. Believe it or not, they’re better adjusted than the lone wolves.”

“Yo,” Ismail called to Carol. “I going back to L.A. with my homie there,” he said, pointing at Pellam.

“I don’t recall that being on the agenda, young man.” He raised his eyebrows to Carol.

“No, no, it’s cool, cuz. I come with you. Hook up with a Blood or Crip crew. I get myself jumped in with them. Be cool. You know what I’m saying.” He vanished down the alley.

“Give me lesson,” Pellam said. “Gangs 101 in Hell’s Kitchen.”

Carol’s glasses had reappeared. He wanted to tell her she looked better without them. He knew better than that.

“Gangs, huh? Where do I start? All the way back to the Gophers?” Carol smiled coyly. Then she laughed in surprise when Pellam said, “I heard One-Lung Curran’s outa business now.”

“You know more than you’re letting on.”

Pellam remembered an interview with Ettie Washington.

“… Battle Row, Thirty-ninth Street, the turn of the century. Grandma Ledbetter told me what a dreadful place it was. That’s where One-Lung Curran and his gang, the Gophers, hung out – in Mallet Murphy’s tavern. Grandma’d go to dig in bins for scraps of gabardine, or maybe look for knuckle bones and she had to be careful ’cause the gang was always shooting it out with the police. That’s where it got the name. They had real battles. Sometimes it was the Gophers that won, believe it or not, and the cops wouldn’t come back for weeks, until things’d settled down.”

He now said to Carol, “How ’bout the gangs now?”

She thought for a moment. “The Westies used to be the gang here and there’re still some around but the Justice Department and the cops broke their back a few years ago. Jimmy Corcoran’s gang’s pretty much replaced them – they’re the dregs of the old Irish. The Cubano Lords’re the biggest now. Mostly Cuban but some Puerto Rican and Dominican. No black gangs to speak of. They’re in Harlem and Brooklyn. The Jamaicans and Koreans are in Queens. The tongs in Chinatown. The Russians in Brighton Beach.”

The director within Pellam stirred momentarily at the thought of a story about the gangs. Then he thought, Been done. Two words that are pure strychnine in Tinseltown.

Carol stretched and her breast brushed Pellam’s shoulder. Accidentally or otherwise.

It had been a remarkable evening, that night eight months ago. The snow hitting the side of the camper, the wind rocking it, the blonde assistant director gripping Pellam’s earlobe between very sharp teeth.

Eight months is an incredibly long time. It’s three quarters of a year. Practically gestation.

“Where’s Corcoran’s kickback?” he asked.

“His headquarters?” Carol asked, shaking her head. “Those boys’re a step away from caves. They hang out in an old bar north of here.”

“Which one?”

Carol shrugged. “I don’t know exactly.”

She was lying.

He glanced at her pale eyes. He was letting her know she’d been nabbed.

She continued, unapologetically. “Look, you gotta understand about Corcoran… it’s not like the gangs on TV. He’s psycho. One of his boys killed this guy’d tried to extort them. Jimmy and some of his buddies cut up the body with a hacksaw. Then they sunk the parts in Spuyten Duyvil. But Jimmy kept one of the hands as a souvenir and tossed it into a toll basket on the Jersey pike. That’s the kind of crew you’re dealing with here.”

“I’ll take my chances.”

“You think he’ll just grin and tell you his life story on camera?”

Pellam shrugged, nonchalant – though an image of hacksaws had neatly replaced the image of making love in a snow-swept Winnebago.

Carol shook her head. “Pellam, the Kitchen isn’t Bed-Sty. It isn’t the South Bronx or East New York… There, everybody knows it’s dangerous. You just stay away. Or you know you’re going to get dissed and you can see trouble coming. Here, it’s all turned ’round. You got yuppie lofts, you got nice restaurants, you got murderers, whores, corporate execs, psychos, priests, gay hookers, actors… You’re walking past a little garden at noon in front of a tenement, thinking, Hey, those’re pretty flowers, and the next thing you know you’re on the ground and there’s a bullet in your leg or an ice pick in your back. Or maybe you’re singing Irish songs in a bar and the guy next to you, somebody walks up and shoots his brains out. You never know who did it and you never know why.”

Читать дальше