No. It would not be that way for Tucker, because he would have his inheritance by then. His father would be dead, his problems solved. It was, he thought, a sad way to have to live: waiting for your father to croak.

Tucker studied the house one last time to make sure he knew what he was doing. All four of the ground-floor windows which had light behind them were to the left; the six dark windows on that level were all on the right of the huge white double doors. Tucker nodded toward the unlighted glass and said, "One of those."

"Not the doors?" Harris asked.

"Bound to be locked," Tucker said. "Try for the next to the last window. The telephone wires feed in there, too."

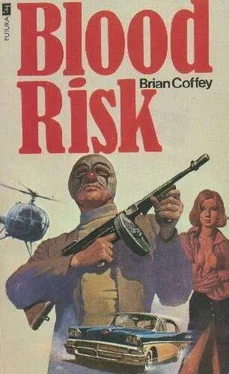

The submachine gun held at hip level in one hand, his finger on the trigger, clutching the silenced Lüger in the other hand, Harris got up and ran lightly, quickly, to a place along the front wall to the left of the second window. No one cried out.

"Go," Tucker said.

Shirillo followed Harris without incident.

Tucker brought up the rear, used a small set of shears that he carried in his windbreaker to cut the telephone wires as planned. He had stopped directly before the window which he was going to open, but he saw no use in shielding himself from it. If anyone was in the room beyond, he was going to know about Tucker soon enough when he cut the glass.

Move ass.

Tucker unbuckled his belt of tools and handed it to Shirillo. He'd intended to break into the house himself, because he trusted his own ability to make the entrance in silence. Now, he belatedly realized that Shirillo must be good at this (why else would he own a custom-made set of tools?) and that the boy would get them in faster since the instruments and the pouch were his and were more familiar to him than to Tucker. "Ever done this?" Tucker asked unnecessarily, in as low a voice as he could use and still be heard.

"Often."

Tucker nodded, stepped back, took Shirillo's pistol and watched him as he knelt before the dark glass.

Pete Harris turned and faced the longest length of the mansion, waiting for someone to appear at the far end of the promenade or to step out of the front doors. If they came through the doors, they'd be near enough to be taken out with the pistol; if they came from the far end of the house, however, a pistol shot wouldn't be accurate, and the Thompson would come in handy. He held both weapons slack in his hands, parallel with his legs, so that they would not unduly tire his arms but so he could bring them up fast in an emergency.

There very well might be one, too.

Tucker wished the place were less well lighted. Directly above his head, in the promenade ceiling, a hundred-watt bulb burned inside a protective wire cage.

Tucker faced away from Harris, in the opposite direction, and thought it might be a good idea to step to the corner of the house where he could command a view of the side lawn as well as of the driveway. He took a single step in that direction just before one of Baglio's men appeared.

He was tall and lean and broad across the shoulders, not at all stupid-looking but stamped by the same die as the gunmen who had been riding in the back of the Cadillac when Tucker and the others had forced it to stop on the mountain road only two days ago. Perhaps he was one of them. He was strolling along, distracted by his thoughts, slouched into himself as if he had been folded at the middle. He was looking at the ground in front of his feet. He didn't suspect a thing. Abruptly, however, as if he had been warned by some extrasensory perception, a sudden clairvoyance, he snapped his head up, his eyes wide, hand moving beneath his jacket with the oiled sureness and the economy of movement that signified a trained professional.

No, Tucker wanted to say. Don't make me. Relax. You haven't got a chance, and you know it.

The gunman had his pistol half in the open when Tucker put a shot into him, high in the chest, by the right shoulder.

The gunman dropped his pistol.

It clattered softly on the concrete promenade floor.

The shot had pushed him half around, so that he leaned back against the wall and, just now beginning to reach for his shoulder, fell forward and lay still.

Despite the high risk associated with his profession, Tucker had only twice been pressed into a position where he had no choice but to kill a man. Once, it had been a crooked cop who tried to force his point with a handgun; the second time it was a man who'd been working with Tucker on a job and who'd decided there was really no sense in splitting the proceeds when one shot from his miniature pearl-handled revolver would eliminate that economic unpleasantry and make him twice as rich. The cop was fat and slow. The partner with the pearl-handled revolver was as affected in every habit as he was in his choice of handguns. He didn't choose to shoot Tucker in the back, which would have been the smartest move, but wanted instead to explain to Tucker, in the course of a melodramatic scene, in very theatrical terms what he intended to do. He wanted to see Tucker's face as death approached, he said. He'd been very surprised when Tucker took the revolver away from him, and even more surprised when, during the brief struggle, he was shot.

Both kills had been clean and quick, on the surface; but both of them had left an ugly residue long after the bodies had been buried and begun to rot. For months after each murder Tucker was bothered by hideous nightmares in which the dead men appeared to him in a wide variety of guises, sometimes in funeral shrouds, sometimes cloaked in the rot of the grave, sometimes as part animal-goat, bull, horse, vulture, always with a human head-sometimes as they looked when they were alive, sometimes as children with the heads of adults, sometimes as voluptuous women with the heads of men and as balls of light and clouds of vapor and nameless things that he was nonetheless able to identify as the men he had killed. In the few months immediately following each kill, he woke nearly every night, a scream caught in the back of his throat, his hands full of damp sheets.

Elise was always there to comfort him.

He couldn't tell her what had caused the dreams, and he would pretend that he didn't understand them or, sometimes, that he didn't even remember what they had been.

She didn't believe him.

He was sure of her disbelief, though she never showed it in her manner or in her face and never probed with the traditional questions. She could not know and could hardly suspect the real cause of them, but she simply didn't care about that. All she was interested in was helping him get over them.

Some nights, when she cradled him against her breasts, he could take one of her nipples in his mouth as a child might, and he would be, in time, pacified in the manner of a child. He wasn't ashamed of this, only welcomed it as a source of relief, and he did not feel any less a man for having clung to her in this manner. Often, when the fear had subsided, his lips would rove outward from the nipple, changing the form of comfort she offered, now offering her a comfort of his own.

He wondered how other people who had killed handled the aftermath, the residue of shame and guilt, the deep sickness in the soul.

How, for instance, did Pete Harris handle it? He'd killed, by his own admission, six men during the last twenty-five years, not without cause-and countless others before that, during the war when he had carried the Thompson and used it indiscriminately. Did Harris wake up at night pursued by demons? Dead men? Minotaurs and harpies with familiar human faces? If he did, how did he comfort himself, or who comforted him? It was difficult to imagine that lumbering, red-faced, bull-necked man in the arms of someone like Elise. Perhaps he never had been consoled and nursed out of his nightmares. Perhaps he still carried them all inside him, a pool of that dark, syrupy residue of death. That would explain the bad nerves as well as anything.

Читать дальше