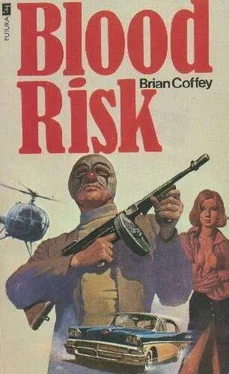

Dean Koontz - Blood risk

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Dean Koontz - Blood risk» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Blood risk

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:0860071677

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Blood risk: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Blood risk»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Blood risk — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Blood risk», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

They struck out for Baglio's mansion, while the night closed in around them, and the silenced crickets near the Buick, alone again, took up their chirruping.

Their line of march paralleled the main highway, though they remained out of sight of it. In a while they came across Baglio's private macadamed lane. Moving back into the woods again, still guided by the flashlight beam, they followed the twisting lane as it cut inland, and they began to move upward into worn limestone foothills. The trees were thick, as was the brambled underbrush. But deer, smaller animals and the run-off from rainstorms had pressed paths through the weaker vegetation. These natural trails often wandered considerably between two points, but they afforded an easier way than any of the men could have chosen with the jumble of bushes, rocks, gullies and brambles on all sides. To make up for the extra distance they had to cover, they jogged thirty paces for every ten they walked, running as far as they could for three minutes, cutting back to a walk for one, running another three, walking again. Tucker wanted to be within sight of the mansion by three-thirty and inside of it no later than a quarter to four. That still gave them plenty of time before dawn to do everything they would need to do.

Running through the darkness with the crazily bobbing light picking out the narrow trail ahead of him, Tucker was reminded of the nightmare that he had experienced in Harris's hotel room: the hand descending suddenly out of shadows, moving stealthily through bands of darkness and blue light, stalking the nude Elise.

He could not shake off the insane conviction that the same hand was behind him now, that it had already disposed of Harris in a most brutal fashion, that it was wrapping around Shirillo at that very moment and would be gripping him in cold iron fingers any time now.

He ran, then walked, then ran some more, listening to the matching steps of the two men behind him.

Twice they stopped to rest for exactly two minutes at a stretch, but they did not speak to each other. Drawing breath was all they cared about. They stared at the ground, wiped sweat out of their eyes and, when their time was up, moved on again. Harris's breathing was the most labored, whether from exhaustion alone or from fear as much as weariness Tucker couldn't say. A life of crime wasn't meant for any but young men.

Fifteen minutes after they had started out, Tucker flicked off the flashlight and slowed their pace considerably. At 3:35 in the morning they came to the perimeter of the forest and the beginning of Baglio's immaculately cared-for lawn.

In the forest, as they were on the way up from the picnic area where they had changed clothes, a thin layer of ground fog had clung to the bottoms of the trees and twined through the undergrowth like a tangle of wispy rags, now and again obscured the way ahead, cold and wet and clinging. Here in the open the aisles of trees funneled the fog between them, poured it onto the shrub-dotted lawn where it lay like piles and piles of heavy quilts. The lights on the front promenade, under the pillars, were diffused by it, as were the dimmer lights that shone through a few downstairs windows. The result was an eerie wash of yellow light that filled the immediate lawn about the house but illuminated nothing, lay upon the dense shadows but did not disperse them.

Tucker, Harris and Shirillo lay in the woods at the edge of the mowed grass and studied the stillness of the early-morning scene, not wanting to find any movement up there but more or less resigned to it. Apparently there were no guards prowling the grounds, though one or more of them might be stationed at fixed points from which they could scan the entire lawn. Tucker knew that was a strong possibility, but he pretty much rejected it anyway. Baglio would not be expecting them to return. There was no reason for him to mount an extraordinary guard tonight unless he had been especially impressed with the state-police helicopter during the day. That was possible, Tucker supposed, but not very likely. Baglio's sort did not like policemen much, but they were not as paranoid about them as a lesser criminal-say, a common burglar or mugger-might have been. For Ross Baglio, there were always payoffs that could be made, influence that could be bought; or, failing that, there were always top-notch lawyers, bail bonds and an eventual dismissal of the charges on one ground or another.

"Probably inside the house this early in the morning, this kind of weather," Harris whispered.

"Of course," Tucker said.

"As planned, then?"

"As planned."

Harris went first. He crouched so that he was only half his normal height, and he ran toward a line of shrubbery that ringed the inside of the circular driveway and provided a well-concealed vantage point from which they could safely gauge the presence of sentries at any of the front windows. For a moment there was the sound of his receding footsteps, soft, wet hissing as he disturbed the dewy grass. Then there was nothing at all. The fog swallowed him completely.

"He'll be in place now," Tucker whispered.

"Right," Shirillo said.

The boy ran now, making even less noise than Harris had, bent even lower. The heavy fog opened up and swallowed him too, in one gulp, leaving Tucker completely alone.

And alone, Tucker remembered the nightmare more vividly than ever: the shadows and the light, the reaching hand. He felt an itch between his shoulder blades, a dull cold ache of expectancy in the back of his neck.

He rose and, crouching, ran to join the others.

They lay on their stomachs behind the evenly trimmed hedge on the inside of the driveway fifty yards from the front doors of the mansion. Through breaks in the foliage they had a good view. The fog was not thick enough to shroud the house altogether at such a short distance, but it did dull the outlines of the roof and softened the joints between slabs of siding so that the place appeared to be made of a single piece of expertly carved alabaster. From their position they could see all the windows on the front of the house: four of them backed by dull yellow light, six of them perfectly dark on the first level; all ten windows on the second floor were dark.

"Been watching," Harris said.

"And?"

"I don't think anyone's at the windows."

"That's unlikely."

"Just the same Watch them and see."

Five minutes later Shirillo said, "I don't see anyone, either."

"Four windows are lighted," Tucker said.

Harris said, "I didn't say there wasn't anyone inside there, awake. I just don't think there's anyone watching the windows. Probably that's because of the fog; they figure they wouldn't see much of anything even if there was something to see."

In a few minutes Tucker was willing to agree that they were not being watched. If one of Baglio's men were standing at any of the front windows, on either floor, in a darkened room, he would most certainly be visible as a lighter gray blur against the deeper blackness of the room behind him. There was only half a moon, and the light from that was considerably diluted by the fog; still, a man's face positioned only inches from the glass ought to reflect enough light to stand out plainly to any knowledgeable observer. The lighted windows, of course, would have clearly revealed any posted guard; those windows were empty, the rooms beyond them apparently quiet and still.

"Well?" Harris asked.

Nerves. A case of nerves. After all, he was twenty-five years in this business, with two tours of a federal prison already behind him. He was too old and had weathered too much to risk getting shot down by a Mafia gunman in the pursuit of something as quixotic as tonight's goal; they would bury him above the house, in the woods, where his body would decompose, the component minerals washing down the slope to fertilize a hood's landscaped estate. In the grave, the only things that would survive the flesh were his bones-and the vinyl windbreaker with its alligator insignia. So Harris had a case of nerves. Of course, everyone had nerves; that definition of his condition was imprecise. Still, one day Tucker would be the same as Harris, tensed to the breaking point, promising himself he would retire, taking that "one last job" over and over again, until his case of nerves led to one final misjudgment.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Blood risk»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Blood risk» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Blood risk» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.