"Hey!"

Tucker blinked.

"You all right?" Pete Harris asked, shaking his shoulder gently but insistently. "You okay, friend?"

"Yeah," Tucker said, not opening his eyes.

"You sure?"

"I'm sure."

Tucker sat up and rubbed his eyes, massaged the back of his neck and tried to decide what had crawled into his mouth and died during his nap in Harris's hotel bed. He flicked his tongue around and didn't find any corpse, decided that he must have swallowed it and that he would have to scrub his teeth well to get rid of the last traces of its demise.

"Jimmy's here," Harris said. "He's got everything you told him to bring back."

Tucker looked up, saw Shirillo across the bed, sitting in a chair by the standard-model hotel writing desk. Several paper bags with store names on them rested on the floor near his feet. "What kind of job did your uncle do on the photographs?"

"Great," Shirillo said. "Wait till you see them."

"Have them ready for me," Tucker said. He got up and went into the bathroom, closed the door behind him. He felt like hell, stiff and weary, though he had been asleep for only an hour and a half. He looked at his watch. One o'clock in the morning. Make it a two-hour nap. Still and all, he should not feel as bad as this. He splashed water in his face, dried off, found Harris's toothpaste and squeezed a worm of it onto his index finger, then scrubbed his teeth without benefit of a genuine brush. It didn't do much good for the tartar that had built up since this morning, but it freshened his breath and made him feel somewhat more human than he had when he woke up.

Back in the main room, he found that they had positioned the three chairs at the writing desk and had a stack of 8 x 10 glossies lying there for his inspection. He took the middle chair which they had left for him and picked up the stack of pictures, went through them carefully, selected a dozen and gave the rest to Shirillo. The boy put them in a plain brown envelope and put the envelope out of their way.

"We'll be ready to go in half an hour," Tucker told them, "if you pay attention the whole way through."

"You have it all figured out?" Harris asked.

"Not all of it," Tucker said, aware of Harris's streak of stubbornness. The big man had gone along with everything Tucker ordered up to now, but he would have his limits. It was best to make him think he played an equal role in at least part of the planning. "I'll want your comments and suggestions so we can hammer out the fine points."

"What if Bachman's dead?" Harris asked.

"Then we're wasting our time, but we don't lose anything."

"We could get killed," Harris said.

"Look at the photographs, please," Tucker said. "They cost me nearly three hundred dollars."

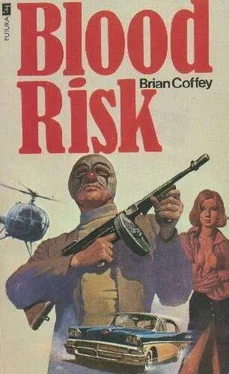

Harris shrugged and settled back in his chair, quiet. He looked at the photographs, listened to what Tucker had to say, looked as though he wanted to put his Thompson together and caress it for a while, began to make a few suggestions and finally regained his nerve. He was getting old, with twenty-five years in the business; no one blamed him for being a little more on edge than his colleagues. They'd be the same way in two more decades, if they lived that long.

On the drive out of the city, Shirillo behind the wheel of a stolen Buick that Tucker had picked up only a few blocks from the hotel, Harris in back with his Thompson across his lap, Tucker hungrily devoured two Hershey chocolate bars and watched the occasional headlights of other cars blur by them. He had not eaten since breakfast, but the candy stopped his stomach growling and steadied his hands, which had become slightly palsied. The food did not, however, do anything about the shakes that had hold of his insides, and he resisted an urge to hug himself for warmth.

Eventually, they pulled off onto the familiar picnic area three quarters of a mile beyond Baglio's private road and stopped behind another car.

"It's empty," Shirillo said.

Harris had leaned forward, and he said, "Couple of kids parking."

Shirillo grinned and shook his head. "If it was that, the windows would be all steamed."

"What do we do?" Harris asked.

Wishing he had another Hershey bar, Tucker said, "We sit here and wait, that's all."

"What if nobody shows up, my friend?"

"We'll see," Tucker said.

A minute later two tall, well-dressed black men walked out of the woods behind the picnic area, making casually for the parked car, one of them still zipping up his fly.

"The call of nature," Shirillo said. "You'd think the state could afford a few comfort stations along a highway like this."

The black men gave the Buick only a cursory glance, not at all afraid of whom they might encounter in a lonely spot like this, got into their own car, started up and drove away.

"Okay,' Tucker said, getting out of the car.

Harris rolled down his window and called to Tucker, "Maybe we ought to hide it better than we planned-in case there's anyone else with a bad bladder problem."

"You're right," Tucker said.

Using a flashlight, Tucker inspected the edge of the woods, found a place between the trees where the Buick could squeeze through, motioned to Shirillo. The kid drove the big car into the woods, following Tucker as he cautiously picked out a route that led deeper and deeper into the underbrush. Fifteen minutes later he signaled Shirillo to stop. They were more than a hundred yards from the last picnic table, two hundred from the road, screened by several clumps of thickly grown mountain laurel.

Getting out of the car, Harris said, "Anybody who's prude enough to walk all this way from the road just to take a piss deserves to be shot in the head."

Shirillo and Tucker quickly unloaded all the gear from the Buick and put it on the car roof where everyone could get at it. Quickly they undressed and changed into the clothes which Shirillo had purchased earlier in the evening according to the sizes they had given him. Each man wore his own black socks and shoes, dark jeans that fitted loosely enough to be comfortable in almost any circumstance, midnight-blue shirt and dark windbreaker with large pockets and a hood that could be pulled over the head. Each man drew up his hood and fastened it beneath his chin, tied the drawstrings in a double knot to keep them from loosening.

Harris said, "You sure have rotten taste, Jimmy."

"Oh?"

"What's the alligator patch on the windbreakers?"

Shirillo reached down and fingered the embroidered alligator on his left breast. "I couldn't find any windbreakers without them," he said.

"I feel like a kid," Harris said.

Tucker said, "Relax. It could have been worse than an alligator. It might have been a kitten or a canary or something."

"They had kittens," Shirillo said. "But I ruled those out. They also had elephants and tigers, and I couldn't make up my mind between those and the alligators. If you don't like the alligators, Pete, we'll wait here while you exchange your jacket for another one."

"Maybe I'd have liked the tiger," Harris said reflectively, letting the idea roll around in his mind while he spoke.

Tucker said, "What's wrong with elephants?"

"Oh, elephants," Harris said. "Well, elephants always look a little stupid, don't you think? They certainly aren't ferocious; they don't instill fear in anyone. Baglio saw me coming in an elephant-decorated windbreaker, he might think I was the local Good Humor man or someone selling diaper service, something like that. Besides, I've been a lifelong Democrat, and elephants aren't my insignia."

"You vote?" Shirillo asked, surprised.

"Sure, I vote."

Both Shirillo and Tucker laughed.

Harris looked perplexed, rubbed at the alligator on his chest and said, "What's wrong with that?"

"It just seems strange," Tucker explained, "that a wanted criminal is a registered voter."

Читать дальше