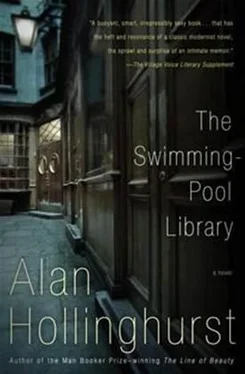

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I flipped about through the notebooks, picking on odd sentences, getting caught for a paragraph, but feeling irritated, almost piqued by the way the life in them went parochially on. I suppose I expected them to fall open at the dirty bits, but they were discreet enough to fall open at records of duties, quarrels with officials, guest-lists for parties. More than that, I expected there to be dirty bits, and the slightly repellent introduction to the trivia of colonial existence gave me sudden doubts. It was the awful sense of another life having gone on and on, and the self-importance it courted by being written down and enduring years later, that made me think frigidly that I wasn’t the man for it.

It was really the present which reassured me. Charles’s life now was so incoherent, such a mixture of fatigue and obsessive, vehement energy, of knowing subtlety and juvenile broadness, of presence and absence, that he gave me the hope which the books withheld. The more recent incident at his house, for instance, was excellent copy. From what I could gather, he had been locked in the dressing-room by Lewis, not as a punishment but to protect him, and prevent him from interfering while Lewis fought with another man in the bedroom. This man was a previous employee. I asked Charles why he had come to the house, and rather guessed that he had been invited as a possible replacement for Lewis. Lewis, as I already knew, was a model of jealousy, and I could easily imagine his slothful, sarcastic violence breaking out if his pitch was queered. Yet if he had fought for his devotion to Charles, why had he then attacked him through the schoolboy voodoo of the effigy? Like all the other miscellaneous symptoms, it made sense to Charles himself. He castigated himself after he woke up and we went down to the kitchen and made tea. ‘It was bound to happen,’ he felt. But he was unable to explain it to me. ‘Lewis was a damn good scrapper,’ he said several times.

The phone rang. When I answered it, a formal and affected voice said, ‘Is that William?’

‘Speaking.’

‘I have Lord Beckwith on the line for you.’ Some thirty seconds elapsed before my grandfather picked up the receiver. He had become so very grand that he commanded servants to do even the simplest things for him. His butler was an efficient, humourless man, almost as old as himself, one of a race virtually extinct, stifled by their own correctness. He would never, one felt, have locked his employer in his dressing-room. This was the first time, though, that he had been commissioned to dial my number, and I felt that slight anxious remoteness that thousands must have experienced during my grandfather’s life in government and the law.

‘Will? How are you, darling?’ This was the other side of his magnificence, the unhesitating intimacy and charm that, more than the talent to command, had meant power and success. His endearments were not amative or effete, but manly like Churchill’s, and gave one a sense of having been singled out, of having value. His ‘darlings’ were not public, like Cockney ‘darlings’ or the ‘darlings’ we queens dispense, but private medals of confidence, pinned on to reward and to inspire.

‘Grandpa. I’m extremely well-how are you?’

‘I feel somewhat overwhelmed by the heat.’

‘Is it as hot up there?’

‘No idea. Hotter, I should think. Look, I’ll be in town all next week-will you take me out to lunch?’

‘You’re sure you wouldn’t rather take me out?’

‘I always take you out. I thought we could change it round for once. Of course, I’d suggest coming over to Holland Park, but you can’t cook, can you?’

‘Not at all, no.’ It was our customary bluff, shy patter. ‘You’d regret it deeply. I’ll take you somewhere very expensive.’ And besides, I felt the demands of an ever-intensifying privacy. Very few people came to the flat; I had whittled my social life down almost to nothing. Since my grandfather had more or less bought the flat for me, I churlishly resented any interest in it on his part; he had not been to it since its previous owner had left. Beneath our joky talk lay the awareness, which neither of us would ever have mentioned, that he had given his money to me already. ‘It’s so nice to be paid for!’ he expanded.

Going back to the journals later on I found that they had changed; some of them had noticeably long entries in them, but not, in the two or three I studied, to tell the story of a very complex incident, or gather up several days’ entries. The entries were anyway irregular, and periods of more than a week sometimes elapsed between them. The longer passages, which might start with a routine description, gave way after a paragraph to an earlier period recalled in detail, like a story. One of these, I noticed from the names, was about Winchester, though it had been written up in the course of a visit to the Nuba Hills. I saw Charles retiring from the company of his boorish companions to sit at a little camp table in his tent and reconstruct, amid the boulders and thorn-bushes of Africa, an episode of his English life.

At the time Winchester itself had been recorded in the five-year diary. It was written in a studied, microscopic hand, with tangling ascenders and capital letters which emerged from snakelike scrolls. On the bordered title-page the printer’s lettering (again, that effortful Gothic) announcing ‘This diary belongs to: ____________________’ was outdone by the looping tendrils with which ‘The Hon. Charles Nantwich’ was laboriously rendered in the manner of the signature of Elizabeth I. At a cursory look this diary was unreadable in more senses than one. With a schoolboy’s typical mixture of secrecy and conventionality the entries (which could only cover three lines per day) were written almost entirely in abbreviations.

What was more interesting was to see how, over the five years at the school, the hand had changed, casting off the juvenile fanciness for later, adolescent, affectations. Equally illegible, the writing came to look less monkish and stilted, and took on a passionate, cursive air. Certain characters, ‘d’, for example, and ‘g’, became the subject for worried stylistic amendment and experiment. Little ’e’s, in particular, were restless-now Greekly sticking out their pointed tongues, now curling up in copperplate propriety. I remembered people at school attaching similar prestige to handwriting, though I never did much to adjust my own frankly careless scrawl.

I would certainly have been too slovenly to have stuck, as Charles had done, to the virtually useless annotation of my life in a book for five years. It was one of those changeless schooltime occupations, which have no function beyond themselves, and I was touched to think of Charles as a prefect fitting in the details of match scores and books each evening on the same page that he had used as a new man, his eye flicking back each year over the slowly accumulating trivia. There must have been so much more, for the book showed only the self-imposed thoroughness of the dull-witted or the lonely. I had no doubt that Charles’s wits had been quick; and if he was lonely, then his thoughts would not have been taken up with fixtures and Latin verbs, he would have been living in his imagination.

The next time I saw him was in the pool, where I was thrashing up and down as usual and nearly bumped into him in the underwater gloom. He was not swimming, but floating just off the deep end: head back, hands on hips, his body seemed to be buoyed up by the white balloon of his stomach, and his legs hung down at an angle below. He was quite still, and his pushed-back goggles gave the impression that his eyes had rolled back into his head, while his body was abandoned to a trance. Though to my mind he looked dead, there was something wonderfully natural about the way he just lay on and in the water, as though on a half-submerged lilo; among the heavy swimmers and divers he seemed serenely disengaged, and I was amused, when I realised who it was, that he inhabited the water in a way that was all his own. At every other turn I saw him, from underwater; and he revolved occasionally with little flips of the hands, like some benign though monstrous amphibian. I left the pool without disturbing him.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.