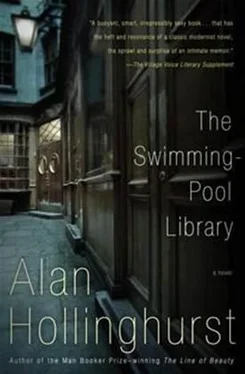

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This was impossible at Bond Street, where even more people got on. The seat I had taken was marked for the use of the elderly and handicapped, but had another claimant come, a figure like Charles, for instance, I would have been prepared to leave the train, when my stop came, with a lurching gait or limb held awry to designate my previously unguessed incapacity. As it was there were merely ordinary commuters and shoppers, though one of the strap-hangers, a man whom I spotted eyeing the erection which even the shortest journey on tube or bus always gives me, inclined to swing or jolt towards me as the train lost or gained speed, and the pressure of his knee on mine, and of his eyes in my lap, irritated me when what I wanted was the boy I could no longer see, and whom I dreaded getting off, unnoticed, at a stop before mine.

It was not until we had passed through the desert of Lancaster Gate and Queensway that there was a major upheaval; at Notting Hill Gate the seat beside mine became empty and the remarkable and inevitable thing happened, as my older admirer, smirking and hesitating, seemed about to take the seat beside me, and the boy from the Corry, materialising suddenly in front of me, and appearing as it were in second place, managed to slip by, almost risking having the older man sit on his lap, and occupied the seat towards which his rival was already lowering his suited rump. Confusion and apology were inadmissible in so bold an action, and he wisely comported himself as if there had never been any question of anyone but him sitting beside me. I drummed my fingers on my knees, and turned to him with a slow, sly grin. The other man’s face grew clenched and red, and he barged away to another part of the car.

Only thirty seconds or so were left before we reached Holland Park, though I could decide, as I had done on occasion before, to stick with somebody I was cruising right through to a station miles beyond my own, where, if the cruise was unsuccessful, I might find myself marooned in a distant suburb, with boys mending their push-bikes on the front paths, shouts of far-off footballers on the breeze, and beyond, the fields and woods of semi-country.

So, as the train began to slow up, I tentatively gathered Charles’s bag to me in a hint, which was reversible if need be, that my stop was next. I was relieved to see, while we agreed that the Corry was indeed too crowded these days, that he also bent forward, ready to stand up. As we elbowed our way out and started along the platform I spotted my other suitor again, savouring the last seconds he might ever see me, and looking almost nauseous as the train pulled away past us and bore him off.

‘Do you live round here, then?’ I said to the boy, across another funny kind of distance.

‘Not exactly, no,’ he said, with something complacent about him that brought back to me my original impression that he wasn’t very nice. I smiled interrogatively. ‘I thought I might come and check out your place, actually,’ he explained.

After some efficient sex, we had a glass of Pimm’s and sat on the window-seat in the evening sun. The air was streaming with seeds, to which Colin was sensitive, and after sneezing and screwing up his eyes for a few minutes, he announced that he had to go. I was not sorry; my mind was already running on to the prospect of opening the bag and getting a feel of what lay ahead. When I closed the door of the flat behind Colin, there the bag was, where I had propped it on a chair before making a grab at him. Retrieving it now, I saw how disrespectful I had been to cast it so hastily aside for the sake of that good but rather professional and chilly trick.

I took the bag into the dining-room, tugged open its straps and pulled the contents on to the table. I closed the window to prevent papers from blowing round; since Arthur’s disappearance I had been a fiend for light and fresh air.

The main part of the archive was a set of quarto notebooks, bound in brown boards, rubbed and worn at the edges-most of them with a clear ink inscription on the front cover; ‘Oxford, 1920’ and ‘1924: Khartoum’ were the first two I picked up. They were written in a fast, elegant and not especially legible hand, in black ink, and there were odd items tucked between the pages-postcards, letters, drawings, even hotel bills and visiting cards. There was also a fat five-year diary, of the kind which can be locked, with other letters and documents, and a large buff envelope bulky with photographs. I drew up a chair at once to look at these, as I believed they would be, although enigmatic, the keys or charms to open the whole case to me.

There were snapshots, group photographs and studio portraits, all mixed up together. A mounted picture of a set of cocky young men was captioned ‘University Shooting VIII, 1921’ in the amateur Gothic script still favoured at Oxford for matriculation and team photos. After a bit I was sure that one of the standing figures, a big boy with swept-back glossy hair and an appealing smirk, must be Charles. The face was far leaner than now, and his whole person seemed well set-up; I had seen him less and less in control of his life, and was surprised for a moment to find a young man who would have known how to have a good time. He appeared again in a more studied portrait, where he was less handsome: the spontaneity and camaraderie, perhaps, of the shooting photo had animated him into beauty.

Most of the pictures, however, derived from his African years. There were predictable snaps of Charles on a camel, with the Sphinx in the background-a tourist memento explained by the inscription on the back, ‘On leave, 1925’. Most of them, though, clearly-or, in many cases, fuzzily-depicted life in the field, and were full of reticent authenticity. Typically, they showed groups of natives, largely or wholly naked, standing round under dead-looking trees, gazing at flocks of goats or herds of cattle. In some Charles appeared, in shorts and sola topi, flanked by robed, shock-headed men of intense blackness. There was one heavily creased photograph of an exquisitely soulful black youth, cropped at an angle, where presumably another figure in the picture had been scissored off. After the scene in Charles’s bedroom this gave me a mild unease, as if it might be a magical act of elimination.

In only one picture did a woman appear prominently. This was a very old-fashioned studio item, in which Charles, still young, and beautifully dressed, leant over the back of a little gilt sofa, on which a pretty, thin-lipped woman was sitting. Behind them the balustrade and pillars of the photographer’s set made as if to recede into a romantically hazy background and to confer on the couple the flushed transience of a Fragonard. Such arcadian hints, however, seemed to have been ignored by the sitters, who appeared tense, and though skilfully grouped by the artist, curiously separate. Had there been a woman in Charles’s life, then, an episode of which this was the unhappy reminder? It seemed more probable that it was a sister; and there was a troubled quality about the eyes of both sitters that suggested some family connexion. Did the people in wherever it was that they hailed from talk of the melancholy and ill-starred Nantwiches? It was certainly time to do that basic research which Charles had already several times recommended to me.

I returned the photographs to their envelope: most of them had no annotation on the back, and though suggestive and informative in a general sort of way, they did little to enlighten me. I did not know how thoughtfully Charles had collected them for me, but it was quite possible that his had not been a very thoroughly photographed career. Evidently doing this job would be as much a matter of probing his memory for links and identifications, as of reading his personalia and getting up the history of the Sudan.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.