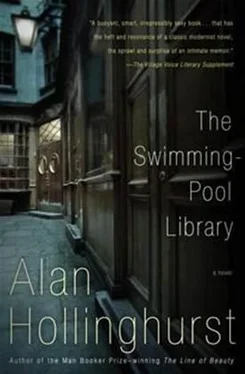

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘It’s a pleasure, sir,’ Abdul assured him with a formal smile.

‘My guest is called William, Abdul.’

‘How do you do,’ I said.

‘Welcome to Wicks’s Club, Mr William,’ said Abdul with a hint of servile irony, lifting the lid off the lean and tightly bound leg of pork on the trolley. Flicking his eyes across to Nantwich he commented, ‘Your guest is not having the pork, my Lord.’

He had a strong presence and I looked at him casually as he cut the meat (which looked slightly underdone) into thick juicy slices. His hands were enormous, though dextrous, and I was attracted by the open neck of his uniform, which gave no suggestion that he wore anything beneath it. As he concentrated the lines of his face deepened, and he poked out his pink tongue.

Nantwich proved to be a voracious eater with poor table manners. Half the time he ate with his mouth open, affording me a generous view of masticated pork and applesauce, which he smeared around his wine glass when he drank without wiping his lips. I attended to my trout with a kind of surgical distaste. Its slightly open barbed mouth and its tiny round eye, which had half erupted while grilling, like the core of a pustule, were unusually recriminatory. I sliced the head off and put it on my side-plate and then proceeded to remove the pale flesh from the bones with the flat of my knife. It was quite flavourless, except that, where its innards had been imperfectly removed, silvery traces of roe gave it an unpleasant bitterness.

‘Tell me why you don’t have a job,’ Nantwich asked after we had busied ourselves with our food for an uneasily long time. ‘We all need a job of work. Christ! Without a job doesn’t one just go do-lally?’

‘It’s because I’m spoilt, I’m afraid. Too much money. I wanted to stay on at Oxford, but I didn’t get a First, though I was supposed to. I did work for a publisher for two years, but then I got out.’

‘I mean, if you want a job I’ll get you one,’ Nantwich interrupted.

‘You’re very kind… I suppose I should do something soon. My father thought he could get me a job in the City, but I couldn’t face the idea of it, I’m afraid.’

‘Your father?’

‘Yes, he’s chairman of, oh… a group of companies.’

‘Your money comes from him, then?’

‘No, as it happens, it’s all from my grandfather. He’s very well off, as you can imagine. He’s settling his estate on my sister and me. We get it all in advance to avoid death duties.’

‘Capital,’ said Nantwich; ‘as it were.’ He munched on for a bit. ‘But tell me, who is your grandfather?’

I had been supposing, somehow, that he knew, and I took a second to rethink everything in the light of the recognition that he didn’t. ‘Oh-er, Denis-Beckwith,’ I then hastened to explain.

Again the sudden emission of interest. ‘My dear charming boy, do you mean to say that you are Denis Beckwith’s grandson?’

‘I’m sorry, I thought you knew.’ Often the intelligence met with a less enthusiastic reception. Then Nantwich’s interest had gone. ‘I suppose you come across each other in the House of Lords,’ I ventured. He had half turned and stared out of the window. When he swung back he leaned close to me and I smelt the pork in his mouth as he said:

‘That chap is a very interesting photographer, indeed.’

‘Really? I don’t think…’ Then I saw that it was one of his conversational hairpins. I followed his glance across the room to where a dapper man, with crisp gold hair going grey, was sitting at the central table. Nantwich made a kind of diving or salaaming motion with his hands, and the man nodded and smiled.

‘Ronald Staines, you must know his stuff, of course.’

‘I’m not sure that I do.’ I was sure he must be a dreadful photographer. ‘What sort of thing does he specialise in?’

‘Oh, very special. You must meet, you’d love him,’ said Nantwich recklessly. I suffered a twinge of the mildly oppressive sensation one gets when one realises that the person one is talking to has plans.

‘Actually, there are lots of people, not yet dead, that I’d like you to meet. All my society is pretty bloody interesting. Falling to bits, of course, ga-ga as often as not, and a coachload of absolute Mary-Anns, I won’t deny it. But you young people know less and less of the old, they of you too, of course. I like young people around: you’re a bonny lot, you’re so heartless but you do me good.’ After this bizarre outburst he sat back and lapsed into one of his vacant spells, occasionally emitting an ‘Eh?’ or giving a shrug. I wondered what his complaint was: not just senility, clearly, as he could be sharp and to the point; was it hardening of the arteries, some slowly spreading constriction that brought on his spasmodic torpor? I knew that I must judge it by medical criteria, although I reckoned that he took advantage of his condition to further the egocentric discontinuities of his talk.

Looking around the room I saw clear cases of other such afflictions, and thought how people of a certain kind gather together as if to authenticate a caricature of themselves-their freaks and foibles, unremarkable in the individual, being comically evident in the mass. As spoonfuls of soup were raised tremblingly to whiskery lips and hands cupped huge deaf ears to catch murmured and clipped remarks, the lunchers, all in some way distinguished or titled, retired generals, directors of banks, even authors, lost their distinction to me. They were anonymous, a type-and it was impossible to see how they could cope outside in the noise and race of the streets. How much did they know of the derisive life of the city which they ruled and from which they preserved themselves so immaculately and Edwardianly intact? As my eyes roamed across the room they came to rest on Abdul, who stood abstractedly sharpening his knife on the steel and gazing at me as if I were a meal.

After doing more than justice to bowls of family-hotel trifle we made our slow progress back to the smoking-room. As Percy poured coffee we were joined by Ronald Staines. He was dressed entirely properly, but there was something about the way he inhabited his clothes that was subversive. He seemed to slither around within the beautiful green tweed, the elderly herringbone shirt and chaste silk tie which plumped forward slightly between collar and waistcoat. His wrists were very thin and I saw that he was smaller than his authoritative suiting. He was a man in disguise, but a disguise which his gestures, his over-preserved profile and a Sitwellian taste in rings drew immediate attention to. It was a strikingly two-minded performance, and, though I found him unattractive, just what I was looking for in the present surroundings.

‘Charles, you must introduce me to your guest.’

‘He’s called William.’ I held out a hand which Staines shook with surprising vigour. ‘We’ve been getting on very well,’ Nantwich added.

‘Don’t fret, my dear, I’m not going to break anything up. Ronald Staines, by the way,’ he said to me. ‘With an “e”.’ He pulled up a chair, not risking to ask if he could join us. ‘And how did you get involved with Charles?’ he asked. ‘Charles has some terrible secret, I’m sure-his success rate with the ragazzi is quite remarkable. He always has some very, very handsome young man in tow.’

I had always been a sucker for this kind of thing, out of vanity, and liked to allow the old their unthreatening admiration.

‘You’re bloody lucky he hasn’t got his camera with him, William,’ said Nantwich. ‘He’d have you stripped off in a moment and covered in baby oil.’ I got the impression of a long-lasting relationship conducted in a bitchy third-person.

‘I have seen photographs of you, though, William,’ Staines recalled. ‘Surely Whitehaven did one, or am I wrong?-little swimming things, and a stripe of shadow covering those dreamy blue eyes? So talented, that young man, though some of his stuff can be a little… strong. Not this one, mind you: I saw it in that New York exhibition-there have been several, I know, but last year, in a kind of abattoir in Soho…’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.