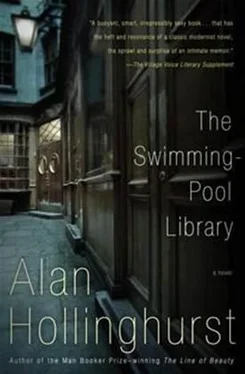

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

That Thursday I had my lunch with Lord Nantwich. I told Arthur I had a long-standing arrangement and he made a point of saying, ‘Okay, man-I mean you’ve got to lead your own life: I’ll be all right here.’ I realised I’d been apologising in a way and I was relieved by his practical reply.

‘You can always have some bread and cheese, and you can finish off that cold ham in the fridge. Anything you want me to get you?’

‘No, ta.’ He stood and smiled crookedly. I didn’t kiss him but just patted him on the bum as I slipped out.

I’d put a suit on, smarter perhaps than I needed to be, but I enjoyed its protective conformity. I so rarely dressed up, and not having to wear a suit for work I seldom took any of mine off their hangers. My father had had me kitted out with morning suits and evening dress as I grew up and I had always relished the handsomeness of dark, formal clothes, wing-collars, waistcoats over braces: I looked quite the star of my sister’s wedding when the pictures appeared in Tatler. But I rarely wore this stuff. I had always been a bit of a peacock-or rather, whatever animal has brightly coloured legs, a flamingo perhaps.

I was a bit late so I took a cab-which also solved the problem of finding Wicks’s. My father was a member of the Garrick and my grandfather a member of the Athenæum, but otherwise I was unsure about London Clubs. I could easily confuse the Reform and the Travellers’, and might well have wandered into three or four of them this morning before hitting on Wicks’s. Cabbies, through a mixture of practicality and snobbery, always know which of those neo-classical portals is which.

‘I’ve come to see Lord Nantwich,’ I told the porter in his dusty glass cabin. ‘William Beckwith.’ And I was told to make my way upstairs to the smoking-room. As I climbed the imposing stairway, lined with blackened, half-familiar portraits, a mild apprehensiveness mingled with a mood of irresponsibility in my heart. I had no idea what we might talk about.

Entering the smoking-room I felt like an intruder in a film who has coshed an orderly and, disguised in his coat, enters a top-secret establishment, in this case a home for people kept artificially alive. Sunk in leather armchairs or taking almost imperceptible steps across the Turkey carpets, men of quite fantastic seniority were sleeping or preparing to sleep. The impression was of grey whiskers and very old-fashioned cuts of suiting, watchchains and heavy handmade shoes that would certainly see their wearers out. Some of those who were sitting down showed an inch or two of white calf between turn-up and suspenders. Fortunately, perhaps in recognition of the dangers involved, almost no one was actually smoking; nonetheless the room had a sour, masculine smell, qualified by the sweetness of the polish with which fire-irons, tables and trophies were brought to a blinding sheen.

Lord Nantwich was sitting at the far end of the room, in front of one of the windows which looked down on the Club’s small and colourless garden. In this context, unlike that in which I had last seen him, he appeared almost middle-aged, robust and rosy-cheeked. I approached him self-consciously, although I reached his chair before his gaze, which wandered halfway between the cornice and a book he had open on his knee, distinguished me.

‘Aah…’ he said.

‘Charles?’

‘My dear fellow-William-goodness me, gracious me.’ He sat forwards and held out a hand-his left-but did not struggle to get up. We shared an unconventional handshake. ‘Turn that chip-chop round.’ I looked about uncertainly, but saw from his repeated gesture that he meant the chair behind him, which I trundled across so as to sit in quarter-profile to him, and then dropped into it, the elegance of the movement overwhelmed by the way the springing of the chair swallowed me up.

‘Comfy, aren’t they,’ he said with approval. ‘ Jolly comfy, actually.’ I hauled myself forwards so as to perch more decorously and nervously on the front bar. ‘You must be dying for a tifty. Christ! It’s quarter to one.’ He raised his right arm and waved it about, and a white-jacketed steward with the air of a senile adolescent wheeled a trolley across. ‘More tifty for me, Percy; and for my guest-William, what’s it to be?’

I felt some vague pressure on me to choose sherry, though I regretted the choice when I saw how astringently pale it was, and when Lord Nantwich’s tifty turned out to be a hefty tumbler of virtually neat gin. Percy poured the two drinks complacently, jotted the score on a little pad and wheeled away with a ‘Thank you, m’lord,’ in which the ‘thank you’ was clipped almost into inaudibility. I thought how much he must know about all these old codgers, and what cynical reflections must take place behind his impassive, possibly made-up features.

‘So, William, your very good health!’ Nantwich raised his glass almost to his mouth. ‘I say, I hope it wasn’t too horrible…?’

‘Your continuing good health,’ I replied, able only to ignore the question, which drew improper attention to what had passed between us; though I also felt a certain pride in what I had done, in a British manner wanting it to be commended, but in silence.

‘What a way to be introduced, my goodness! Of course I know nothing about you,’ he added, as if he might be exposing himself, though morally this time, to some degree of danger.

‘Well I know nothing about you,’ I hastened to reassure him.

‘You didn’t look me up in the book or anything?’

‘I don’t think I have a book to look you up in.’ My father, I thought, would have looked him up straight away; in Debrett, as in Who’s Who , the volumes in his study always fell open at the Beckwith page, as if he had been checking up credentials that he might forget, or that were too remarkable to be readily believed.

‘Well that’s splendid,’ Nantwich declared. ‘We’ve still got everything to find out. What utter fun. When you get to be an old wibbly-wobbly, as one, alas, now is, you don’t often get the chance to have a go at someone absolutely fresh!’ He took a mouthful of gin, confiding in the glass as he did so a remark I could barely make out as it drowned, but which sounded like ‘Quite a corker, too.’

‘It’s an agreeable room, this, isn’t it,’ he observed with one of his unannounced changes of tack.

‘Mmm,’ I just about agreed. ‘That’s an interesting picture.’ I tilted my head towards a large and, I hoped, mythological canvas, all but the foreground of which receded into the murk of two centuries or so of disregard. All that one saw were garland-clad, heavy, naked figures.

‘Yes. It’s a Poussin,’ said Nantwich decisively, turning his gaze away. It so evidently was not a Poussin that I wondered whether to take him up, whether he knew or cared what it was; if he were testing me or merely producing the philistine on-dit of the Club.

‘I think it could do with cleaning,’ I suggested. ‘It appears to be happening in the middle of the night, whatever it is.’

‘Ooh, you don’t want to go cleaning everything,’ Nantwich assured me. ‘Most pictures would be better if they were a damned sight dirtier.’ Mildly dismayed, I treated it as a joke. ‘Bah!’ he went on. ‘You get these fellows-women mostly-doing all the old pictures up. No knowing what they’ll find. And then they look like fakes afterwards.’

I saw he was dribbling gin from his glass onto the carpet. He touched my outstretched hand. ‘Whoopsy!’ he said, as if I were being a nuisance. His gaze drifted into the middle distance and I too looked about, a little at a loss for talk.

‘Actually, I love art,’ he announced. ‘One day, if we get on quite well, I’ll show you my house. You’re keen on art, I should say?’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.