There were people up there, she noticed. They were being carried through the dead city and they looked warm and cozy and cheerful in the belly of the snake train.

The wet snow was denser now, and the wind drove it against her head so she could no longer feel her face. When she noticed the building still under construction, with the fence knocked down and the empty, dark windows, she realized it might be a place she could stay without being discovered. No one could be living there.

And it was dark and quiet in there too, but there were so many windows. She thought the whole world must be able to see her. And it was almost as bitter cold as outside. There were no blankets, no furniture, nothing soft whatsoever. Some of the inside doors were missing. The wind whistled through the main hallway, and the wet snow slid quietly down the enormous panes of glass.

A violent contraction came-it felt as if God Himself had grabbed her with His giant hand and squeezed until she was close to breaking apart.

“Stop,” she whispered desperately. “Stop.” If only it would hold off again. If the contractions would stop; if the baby would just stay in there and leave her alone-then maybe she could cross the right bridge to the right country instead of dying in the wrong one.

She crouched down on the tile floor beside a toilet bowl because she felt least visible there. But the sounds from inside kept coming, and what good did it do to hide?

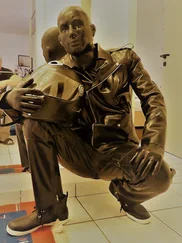

Here there is no one, she told herself. The building is empty, it is unfinished. No one can hear you now. But suddenly there was someone. She hadn’t even heard him come in. She just opened her eyes and there he was. Her heart took a long, hovering leap and ended up stuck in her throat.

He was just a silhouette in the dark, a darker outline, and the glare from the flashlight blinded her even more. A moment earlier she had thought she would die either from the cold or from her baby. Now another possibility had shown up.

“Leave me alone,” she said, but of course he didn’t understand her.

The man said something, and she realized he wasn’t the only one there.

“Don’t kill me,” she said.

And he didn’t. To her amazement he took off his coat and put it around her shoulders.

His name was Taghi. She understood that much from his words and gestures, even though they shared almost no common language. And he was trying to help her. This was so strange that she could barely comprehend it. His hands were friendly, his tone of voice reassuring. And he said one word she understood.

“Doctor,” he said in English. “We will get you to a doctor.”

“No,” she answered, the word scaring her. “No doctor.”

“It is okay,” he said, slowly and clearly. “It is a secret doctor. Okay? You understand? Secret doctor okay.”

She couldn’t answer. The next contraction hit her, and she was only vaguely aware that he brought out a cell phone and called the okay secret doctor.

Nina was staring at the vending machine when the telephone rang. For a measly five kroner you could choose between coffee with cream, coffee with sugar, coffee with cream and sugar, bouillon, pungently sweet lemon tea, and cocoa. Unsweetened and uncreamed coffee had once been options, but they had been eliminated sometime in the mid ’90s, if those who had been here even longer than her were to be believed.

It’s Morten, she thought, without taking the phone from her white coat. And he’ll be pissed with me again.

She was tired. She had been on duty since seven that morning, and the Danish Red Cross Center at Furesø, commonly known as the Coalhouse Camp, was every bit as ravaged by December flu as the rest of Copenhagen, with various traumas and symptoms of depression thrown in, plus an epidemic of false croup among the youngest children in Block A.

Despite all that, she could have been home by now. If she had left at four, after the evening nurse delayed by the snowstorm had finally shown up, she could have been sitting right now in their apartment in Østerbro with a cup of real coffee and a few of the slightly deformed Christmas cookies Anton had baked in the SFO, his youth center. Why hadn’t she? Instead of hanging out on a tattered, tobacco-stained sofa in the Block A lounge, listening through the walls to Liljana’s thin cough, her professional ear focused. How obstructed was the child’s respiratory tract? How much strength was there behind each cough? Should she be suctioned again, and when was the last time her temperature had been taken?

The sick-staff excuse was about as worn out as the sofa-Morten wasn’t buying it any longer.

“Damnit, Nina. She’s your mother!” he had hissed the last time she had called home to say she’d be late. He was supposed to be going to some sort of show with the others from his work, and if she wasn’t there it would be the second night in a row that Nina’s mother would be alone with the kids.

The phone began to repeat its cheery little electronic theme. Reluctantly, Nina grabbed it out of her coat’s pocket.

It wasn’t Morten. It was an extremely frantic voice she didn’t recognize until he said his name.

“It’s Taghi. You have to help. There’s a woman, and she’s… she’s about to have a baby.”

Even then it took her some time, for Taghi had been out of the Coalhouse Camp for three years, and there had been so many others since then.

“Take her to the hospital,” she said, even though she knew that wasn’t an option. Not when he was calling her.

“No,” he replied. “She’s from Africa. She won’t go to the hospital. You have to help.”

I’m not a doctor or a midwife. The words were in her mind, but she didn’t speak them. Her exhaustion was already gone. Adrenaline shot into her blood, she was clear-headed and energetic. Morten will have a fit, she thought. But this would be so much easier than trying to explain to him why she couldn’t handle spending another night alone with her own mother after the kids went to sleep.

She set the plastic cup of lukewarm coffee with cream down on the scratched table. “What’s the address?” she asked.

Taghi glanced at his watch. Wasn’t it about time she got here? He was out of his league here, he wanted so badly to hand over this woman and baby and the contractions and birth to someone trained for it. He was a man, damnit. He shouldn’t even be here.

He heard a sharp metallic click, and suddenly the whole apartment was bathed in a piercing white light from the spots set into the ceiling.

The woman crouching on the floor grabbed desperately for his arm. Taghi heard Djo Djo and Farshad swearing softly out in the kitchen area. A second later they stood beside Taghi in the small bathroom, where they both squeezed their way in behind the wall, the only thing shielding them from being in full view from the street outside.

Someone had walked into the hallway, and Taghi immediately assumed it was the police, and thought that the residency permit he’d worked so hard for was about to go up in smoke right now, right here, in front of the entire fucking district of Ørestad. Someone had turned on the building’s electricity and the harshly lit apartment made him feel like a fish in a very small aquarium. The bathroom was the only place to hide. He caught Djo Djo’s eye and held his index finger to his lips, warning him.

The footsteps outside rapped sharply against the tiles. Whoever they were, they weren’t afraid of being heard. They walked past the door and stopped farther down the hallway. There were at least two of them, maybe more.

The dark-skinned foreigner on the floor fidgeted and held both hands over her eyes, as if to protect herself from the whole world. Another contraction was on its way. Her backbone formed a round, taut bow underneath her summer jacket, Taghi noticed; soon she would be moaning again. Soon they would be discovered.

Читать дальше