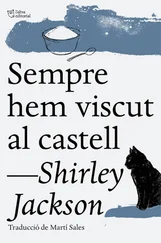

Shirley Jackson - We Have Always Lived in the Castle

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Shirley Jackson - We Have Always Lived in the Castle» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2006, ISBN: 2006, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Триллер, gothic_novel, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:We Have Always Lived in the Castle

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2006

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-101-53065-8

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

We Have Always Lived in the Castle: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «We Have Always Lived in the Castle»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a deliciously unsettling novel about a perverse, isolated, and possibly murderous family and the struggle that ensues when a cousin arrives at their estate.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «We Have Always Lived in the Castle», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“It was all so long ago,” Charles said.

“You should have kept notes,” Uncle Julian said.

“I mean,” Charles said, “can’t it all be forgotten? There’s no point in keeping those memories alive.”

“Forgotten?” Uncle Julian said. “Forgotten?”

“It was a sad and horrible time and it’s not going to do Connie here any good at all to keep talking about it.”

“Young man, you are speaking slightingly, I believe, of my work. A man does not take his work lightly. A man has his work to do, and he does it. Remember that, Charles.”

“I’m just saying that I don’t want to talk about Connie and that bad time.”

“I shall be forced to invent, to fictionalize, to imagine.”

“I refuse to discuss it any further.”

“Constance?”

“Yes, Uncle Julian?” Constance looked very serious.

“It did happen? I remember that it happened,” said Uncle Julian, fingers at his mouth.

Constance hesitated, and then she said, “Of course it did, Uncle Julian.”

“My notes…” Uncle Julian’s voice trailed off, and he gestured at his papers.

“Yes, Uncle Julian. It was real.”

I was angry because Charles ought to be kind to Uncle Julian. I remembered that today was to be a day of sparkles and light, and I thought that I would find something bright and pretty to put near Uncle Julian’s chair.

“Constance?”

“Yes?”

“May I go outside? Am I warm enough?”

“I think so, Uncle Julian.” Constance was sorry, too. Uncle Julian was shaking his head back and forth sadly and he had put down his pencil. Constance went into Uncle Julian’s room and brought out his shawl, which she put around his shoulders very gently. Charles was eating his pancakes bravely now, and did not look up; I wondered if he cared that he had not been kind to Uncle Julian.

“Now you will go outside,” Constance said quietly to Uncle Julian, “and the sun will be warm and the garden will be bright and you will have broiled liver for your lunch.”

“Perhaps not,” Uncle Julian said. “Perhaps I had better have just an egg.”

Constance wheeled him gently to the door and eased his chair carefully down the step. Charles looked up from his pancakes but when he started to rise to help her she shook her head. “I’ll put you in your special corner,” she said to Uncle Julian, “where I can see you every minute and five times an hour I’ll wave hello to you.”

We could hear her talking all the time she was wheeling Uncle Julian to his corner. Jonas left me and went to sit in the doorway and watch them. “Jonas?” Charles said, and Jonas turned toward him. “Cousin Mary doesn’t like me,” Charles said to Jonas. I disliked the way he was talking to Jonas and I disliked the way Jonas appeared to be listening to him. “How can I make Cousin Mary like me?” Charles said, and Jonas looked quickly at me and then back to Charles. “Here I’ve come to visit my two dear cousins,” Charles said, “my two dear cousins and my old uncle whom I haven’t seen for years, and my Cousin Mary won’t even be polite to me. What do you think, Jonas?”

There were sparkles at the sink where a drop of water was swelling to fall. Perhaps if I held my breath until the drop fell Charles would go away, but I knew that was not true; holding my breath was too easy.

“Oh, well,” Charles said to Jonas, “ Constance likes me, and I guess that’s all that matters.”

Constance came to the doorway, waited for Jonas to move, and when he did not, stepped over him. “More pancakes?” she said to Charles.

“No, thanks. I’m trying to get acquainted with my little cousin.”

“It won’t be long before she’s fond of you.” Constance was looking at me. Jonas had fallen to washing himself, and I thought at last of what to say.

“Today we neaten the house,” I said.

Uncle Julian slept all morning in the garden. Constance went often to the back bedroom windows to look down on him while we worked and stood sometimes, with the dustcloth in her hands, as though she were forgetting to come back and dust our mother’s jewel box that held our mother’s pearls, and her sapphire ring, and her brooch with diamonds. I looked out the window only once, to see Uncle Julian with his eyes closed and Charles standing nearby. It was ugly to think of Charles walking among the vegetables and under the apple trees and across the lawn where Uncle Julian slept.

“We’ll let Father’s room go this morning,” Constance said, “because Charles is living there.” Some time later she said, as though she had been thinking about it, “I wonder if it would be right for me to wear Mother’s pearls. I have never worn pearls.”

“They’ve always been in the box,” I said. “You’d have to take them out.”

“It’s not likely that anyone would care,” Constance said.

“ I would care, if you looked more beautiful.”

Constance laughed, and said, “I’m silly now. Why should I want to wear pearls?”

“They’re better off in the box where they belong.”

Charles had closed the door of our father’s room so I could not look inside, but I wondered if he had moved our father’s things, or put a hat or a handkerchief or a glove on the dresser beside our father’s silver brushes. I wondered if he had looked into the closet or into the drawers. Our father’s room was in the front of the house, and I wondered if Charles had looked down from the windows and out over the lawn and the long driveway to the road, and wanted to be on that road and away home.

“How long did it take Charles to get here?” I asked Constance.

“Four or five hours, I think,” she said. “He came by bus to the village, and had to walk from there.”

“Then it will take him four or five hours to get home again?”

“I suppose so. When he goes.”

“But first he will have to walk back to the village?”

“Unless you take him on your winged horse.”

“I don’t have any winged horse,” I said.

“Oh, Merricat,” Constance said. “Charles is not a bad man.”

There were sparkles in the mirrors and inside our mother’s jewel box the diamonds and the pearls were shining in the darkness. Constance made shadows up and down the hall when she went to the window to look down on Uncle Julian and outside the new leaves moved quickly in the sunlight. Charles had only gotten in because the magic was broken; if I could reseal the protection around Constance and shut Charles out he would have to leave the house. Every touch he made on the house must be erased.

“Charles is a ghost,” I said, and Constance sighed.

I polished the doorknob to our father’s room with my dust cloth, and at least one of Charles’ touches was gone.

When we had neatened the upstairs rooms we came downstairs together, carrying our dust cloths and the broom and dustpan and mop like a pair of witches walking home. In the drawing room we dusted the golden-legged chairs and the harp, and everything sparkled at us, even the blue dress in the portrait of our mother. I dusted the wedding-cake trim with a cloth on the end of a broom, staggering, and looking up and pretending that the ceiling was the floor and I was sweeping, hovering busily in space looking down at my broom, weightless and flying until the room swung dizzily and I was again on the floor looking up.

“Charles has not yet seen this room,” Constance said. “Mother was so proud of it; I ought to have showed it to him right away.”

“May I have sandwiches for my lunch? I want to go down to the creek.”

“Sooner or later you’re going to have to sit at the table with him, Merricat.”

“Tonight at dinner. I promise.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «We Have Always Lived in the Castle»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «We Have Always Lived in the Castle» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «We Have Always Lived in the Castle» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.