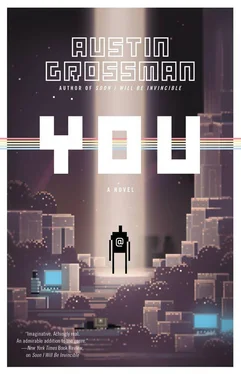

You could walk back and forth in his apartment, look out his window, and see a tiny piece of the Seine through a crack between two apartment buildings. It’s when you’re over by the window that you realize that Nick Prendergast is, very definitely, Prendar the thief. He was more human-looking, but he had the same beaky nose, same eyebrows, same blue eyes, and same slightly weak chin. A shabbier, thoroughly modernized Prendar, residing via dream logic (game logic?) in 1937 Paris. Prendar, voleur, demi-fey.

Of course, I was there on my own secret mission, which had nothing to do with the German spy ring the game would eventually turn out to be about. My leather satchel should have contained a few francs, a Webley automatic pistol with one bullet, and a telegram with an address on it, from which we gather it is the spring of 1937.

As Prendar/Prendergast/whoever, you leave your apartment for the streets of Paris. You could go anywhere, walk to Père Lachaise Cemetery and visit Oscar Wilde’s grave if you liked, but you walk to the address on the telegram, a tailor’s shop on the Champs-Élysées, where you find a suit of evening clothes that has been ordered for you by an unknown party. In the vest pocket there is an invitation to an event at the comte de Versailles’s house, false identity papers, and a note explaining that someone at the party is a spy smuggling weapons and intelligence to the Reich. The world is on the brink of war, but perhaps one man in the right place can hold back the tide a few moments longer. You’re already late for the party.

But this time, it was different. Because when I checked the vest there was an additional inventory item, an object that shouldn’t even have existed in this era, in this world, in this genre. A white Endorian flower. It wasn’t technologically unreasonable that Clandestine could import data from an Endorian saved game—they ran the same code, worked by the same rules. Under the hood, Paris and Endoria were made of the same stuff. But nonetheless it shouldn’t have been there. It was uncanny.

At the comte de Versailles’s I realized how odd the game was, and why Darren had designed it this way. The game concept demanded intrigue, mystery, glamour, and romance. Accordingly, you couldn’t just go around murdering people; there was exactly one bullet in the entire game. Instead, Nick could do things like (F)lirt or (Q)uestion or (W)altz.

The game had a schedule of parties from March to early June, the Paris social season. There was a list of suspects, chosen from the cream of western Europe: artists, aristocrats, and dignitaries. One was secretly a Nazi spy; there was also a Communist mole, an American agent, and a Czech assassin. Darren’s trick was to turn the elite social world of Paris into a system of party invitations, weekend invitations, flirtations, cachet, and deceptions, requiring by turns charm, manners, improvisatory brilliance, and the brash self-assurance of the master party crasher.

You wandered around the drawing room, holding a cigarette that you forget to smoke. You were pretending to be someone called the Baron Pemberly-Sponk. A woman named Laura Mortimer, society reporter for a Paris daily, approached. There was a short, surreal exchange about the cinema, which might or might not have been a coded message. According to the decoder wheel, it wasn’t code at all, just Nick’s native haplessness. Laura looked a lot like Leira with a bobbed haircut.

A young heiress made advances; a mysterious woman in black stared at you, then left the party. What did she want? Did you follow her? The door to the kitchen and servants’ wing swung invitingly ajar—did you dare slip out and explore the house? You are dogged and charming; you struggle politely with your cover identity.

I copied the list of suspects down in pencil. I didn’t care, but it might help me stay alive while I looked for what I needed. As the summer passed, the challenges grew more difficult. You picked locks and copied letters and scrutinized sepia photographs. You spent a great deal of time creeping through the halls of country houses after midnight. You met Unity Mitford and read Evelyn Waugh’s correspondence. The real Pemberly-Sponk put in an unexpected appearance. Laura’s passport turned out to be forged. A rumor circulated that Pemberly-Sponk was in fact a world champion practitioner of the Viennese waltz, and an exhibition of skill was required. The list of suspects narrowed.

I noticed one or two more differences. Laura’s formal dress was a pale blue-and-white chiffon, not green. My CIA contact, Blandon (a dead ringer for Brennan), wore a white shirt with gold cufflinks and a red satin cummerbund. The AIs knew who they were and who they’d been, although there was no sign of Lorac.

Unfortunately, I didn’t care. I was just looking for the homing device Nick was supposed to get access to when he had enough francs stashed away in his cheap mattress—the homing device that would lead us to the cursed sword that shouldn’t exist here, but it did, just as it did in all the worlds. And I found it. Nick pawned his best jacket for it, but I got it. From there, I only needed to survive.

I clicked on the flower, and Prendergast looked at it for a moment, then shrugged and put it in his lapel. Clandestine was a game that cared about wardrobe, so Nick’s character stats reshuffled; a little less intimidating, a little more dashing. The adjustment turned out to have a small but tangible effect. Relationships were all rated on points, and they reshuffled, too.

Laura had been a friend and platonic confidante in the wilds of Paris, but now she gained new conversation options. One night after a party she stopped at the intersection near her apartment.

“Do you love me?” (Y/N)

You stopped for long seconds. Should you? You’d already lied to her. Your name wasn’t Pemberly-Sponk, it was Prendergast. Or Prendar. And even that wasn’t your real name. Your name wasn’t Prendar—was anybody’s? You couldn’t tell her your real real name; it wasn’t in the interface. And should she trust you, the player, who knew she was only numbers? Who just wanted to win the game, to maximize a set of points? Or get a million dollars? And isn’t love only for people who can be trusted?

I pressed Y anyway.

You passed a threshold, and a new scene was unlocked. There was a bonus level. Nick and Laura went spinning together through an enchanted Louis Quinze ballroom whose bay windows overlooked the starlit Seine. The graphics were laughable by the standards of even a few years later, but the scene was no less powerfully imagined for that. It worked on its on technological level, just as a Roman mosaic or cave painting doesn’t seem less powerful for lacking the realism of a Renaissance oil painting. The camera panned along with them through a seemingly endless gallery. Behind them, through the windows, a cartoonish but meticulously correct Paris skyline scrolled past.

The haunting melody of “Laura’s Waltz” had to be one of the finest compositions ever written for the 6581 SID chip. It managed to suggest in three channels of flat eight-bit tones the gaiety and prescient sadness of Paris’s lost generation, the waltz’s plaintive keening and the warbling of its higher registers soaring over the buzzy, percussive bass.

When I heard it playing, it felt like a sound track to that whole lost sophomore year of college, through and past my first failed relationship. I saw myself growing up, all in a few months going from overage teen to disappointed grown-up, and there was that middle space where it all came together, a sixteen-color Paris between the wars. For some reason, I felt as close to having a life as someone who had no life could possibly feel.

And I was thinking about how catching the spy didn’t matter anyway. Maybe I was older, and I knew France was falling, the Reich was coming, history was on its way, and a video-game spy like Nick wasn’t going to stop it. On impulse I stopped outside the tailor’s and dropped my pistol into an open manhole. I didn’t feel like shooting anybody just then.

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)