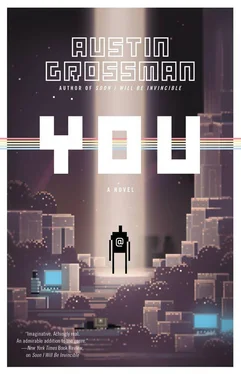

Lisa’s renderer was… odd.

It was certainly fast. It handled the gnarliest, most convoluted sections of the world without any visible slowdown. Matt panned across a broad, expansive scene of assembled warriors, distant trees and castles, a nightmarish number of polys, and Lisa’s renderer just shrugged it off without thinking. It did what we needed it to—it was fast enough to let you forget it was just drawing a bunch of data; it felt like a camera looking into the world we had built, a world you were suddenly part of, immersed in.

But it wasn’t the next-gen tech everyone was expecting. It was almost as if it didn’t want to be. The problem facing realistic real-time computer games is that the real world isn’t a bunch of polygons, it’s rounded and rough and lumpy, and computer games do their best to mimic this, even though it’s the thing they are basically the worst at doing. They’ll use cleverly drawn textures and soft focus and tricky shading and anything else possible to make their world seem just as curvy and squashy as the real one. The world Lisa showed us was overtly angular—faceted, like crystal. The hard planes in the geometry were too apparent. It was all technology, no art. It looked a little like the graphics demos we would occasionally receive from autodidact would-be game programmers, a surprising number of whom lived in former Soviet-bloc nations. They’d have a characteristic look, garishly colored miniature jewel-toned labyrinths built solely to show off their particular arsenal of tricks—giant rotating mirrors and fountains of sparks and glistening waterfalls.

Lisa knew all the tricks, but she seemed to have deliberately turned most of them off. She clearly had some translucency going, and shadowing and specular highlights (the sharp glints you get off metal or water), but she didn’t bother with some of the smoke-and-mirrors stuff.

But the more I looked at it, the more it seemed to have its own style of beauty. In its own way, it was like nothing I had ever seen before.

Whatever else it did, it didn’t strain for effects it couldn’t quite produce. One of the paradoxes of 3-D game technology is that the closer games get to looking as realistic as film, the more they want to just get there, and as a result they spend a lot of time in the uncanny valley, a concept that Gabby taught me. The idea of the uncanny valley is that when you draw people, there are two ways to do it well. You can draw something really simple, such as a smiley face, and it looks okay; or you can have a very detailed and realistic human face, such as a photograph or a Renaissance painting, and that looks okay, too. But in between those two extremes it starts to feel creepy, the way a department-store mannequin does—not obviously unreal or cartoony, but not real enough to seem like a portrait of a real person. Uncanny.

We’d left behind the world of arcade games, with their tiny little icons jumping around; and the technology was moving toward becoming as realistic as the movies. But right then, we were hanging around in the middle, straining to look as good as movies do—good enough to compare ourselves to film, but not looking as real as they do. It was an uncomfortable place to be. Even the flashiest games of any given year only make you want next year’s version sooner. In a way, the earliest arcade games were more comfortable being games.

Lisa’s renderer showed a world that looked… solid. There was nothing it drew that wasn’t legitimately there in the game world—no fake foliage, no doors that were drawn on walls that you couldn’t open. There was a curious, solemn music to it. It didn’t look like anything else. And—thank God—it started up really fast. You ran it and you were in the game.

“Huh,” Don said. I could see it through his eyes—or, rather, I could see him seeing it through the shareholders’ eyes. It wasn’t going to do the job; at least not by itself. The rest of us were going to have to work.

At the end of five weeks, Lisa was curled up in a sleeping bag under her desk. The people working nearby were keeping a respectful silence; the previous night she’d gotten the sky done in a single, heroic fourteen-hour burst of programming. The thing now displayed animated clouds and an incandescent sun that whited out the viewpoint if looked at too long. The sun took ten minutes to pass from one horizon to the other, followed by two mismatched moons that spun overhead through the Endorian night. Both were lumpy and heavily pockmarked, as if battered from too many arcane celestial combats or manifestations of divine wrath.

We were ready, just about. I’d singled out the twenty-minute sequence that ran the engine through its paces, demonstrated at least three of our modes of gameplay (stealth, combat, 3-D movement), and formed its own tidy little dramatic and narrative arc. I’d played through it at least forty times. Not everything was finished, but Lisa and I had hacked together some crude workarounds to make it work as the finished game would. Everything was going to go fine, as long as I followed the script exactly.

I watched a rental car pull into the lot at eight fifty-five, tires crunching the oak leaves no one ever swept out of the lot. With his thick black hair brushed straight back from his forehead, pink button-down shirt open at the collar, and navy blazer, he looked like a high school kid dressed up as an executive for a theater production. But if they wanted, Focus could shut us down tomorrow and cut their losses. I was sure it had been talked about.

“I’m Ryan from Focus Capital. Great to meet you all.”

He shook hands with each of us in turn—Don, Lisa, Gabby, and me—and there was a rapid exchange of business cards. I had never given my business card to anybody before.

I wasn’t sure how to dress for the meeting. In the end I decided they would want people who looked like a hacker would look in a movie—T-shirt and jeans, unwashed hair. I tried to oblige, but when I checked myself in the washroom mirror I looked more like one of the runaways that hang around Harvard Square.

We went to the conference room, where Matt had set up the demo machine, which was about 30 percent faster than anything we developed on and by far the most expensive computer in the office.

I’d been told that Ryan was there as part of due diligence, mostly just to see if we were there at all or if we had stripped the office of its furnishings and fled in the night. But it was clear that he wanted to see the game. He didn’t have any games expertise, but that probably wouldn’t stop him from having an opinion, because everyone everywhere has an opinion about whether they’re having fun and why. In practical terms, he could tell us, “Make the lead character a lovable puppy or else we’ll shut you down.”

Don gave a presentation, talking about our strict adherence to the schedule, our bare-bones budget reduction. He ran through a short list of competing games also slated to come out near Christmas, and ticked off the three USPs—unique selling points—that would distinguish us from other games. After hours of discussion we had decided that these were the game’s high-res textures, its advanced simulation techniques, and its epic story, set in the award-winning Realms of Gold universe.

Don spent twenty more minutes performing the timeworn routine game companies always recite to investors, the story of how they are conquering the world. Precipitous growth of the market through the 1990s, “fastest-growing sector of the entertainment industry,” “young male demographic,” and the inevitable clincher, “In the coming year, video game revenues will equal or exceed that of the motion picture industry.” Everyone had heard it before, but it felt good to say it. He made it sound like—against the evidence of the senses—everyone who had ever touched the game industry was rich. The truth, however, is that games are ridiculously expensive and only the top few games in a given genre make significant money. But whatever happens, we’re still the future of entertainment, right?

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)