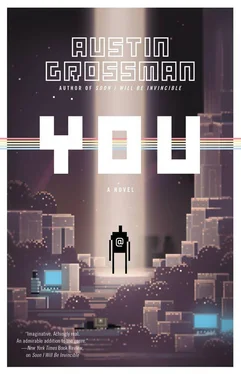

x factor to it; it had never been surpassed or even duplicated. Before Simon died he was working on a project that he claimed would the next generation of the technology. He used the word

ultimate more than once—in fact, right there in the title of his proposal (it was meant to finally get him his BA from MIT; they’d as much as offered it to him, but he never followed through): “The Ultimate Game: A Robust Scheme for Procedurally Generated Narrative.” There had even been a press conference, but no copy of the proposal had ever been found. The idea—the Fermat’s last theorem of video game technology—lingered on at Black Arts.

I should say, people have had the impression Simon killed himself, or else died as part of a game. That was the way it was reported in most of the papers. “A ‘Gamer Death’ on Campus,” as if there were such a phrase. More than one dipshit psychology professor said things like, “It’s not uncommon for these self-identified ‘gamers’ to lose the ability to distinguish between what is a game… and what is reality.”

First of all, this is a viewpoint that is frankly idiotic. People who play games don’t get killed or go crazy any more often than anyone else. It’s just that people point it out when they do. Second of all, Simon was a person with a vocation, one of the few people I’ve ever met for whom this was unmistakably the case. He wasn’t out of touch with reality, he was simply opposed to it. Third of all, fuck reality. If Simon didn’t like the world he grew up in, he has my wholehearted support and agreement. I went to his funeral, as did his many friends. They were not any kind of checked-out gamer fringe; it turns out a dude in a kilt who introduces himself as “Griffin” can be honestly, normatively upset that his friend got killed in a ridiculous accident.

When I heard that Simon had died, I tried to find something appropriate to feel. What I did feel wasn’t flattering. We hadn’t been friends since the early 1980s. I was still young enough to feel the death of someone I’d known as a novelty. Like it was one more aspect of Simon’s eccentricity, or his genius. One more place Simon got to before the rest of us. I felt sorry we’d been out of touch, sorry because we’d both vowed to do the impossible, and it was the only vow I’d ever made, and I hadn’t done it, and Simon—well, that was the thing. I was partly there because I wanted to know what exactly happened. How far Simon had gotten.

I let myself in. I smelled fresh paint; I could hear somebody laughing.

“Hello?” I called into the darkness.

A teenager in a black T-shirt looked out. He was built on a fun-house scale—my height but twice my width, a fat kid with the arms and chest of a linebacker. “Oh, hey. Are you Russell?”

“Yes, that’s me,” I answered, relieved.

“I’m Matt. Hang on.” He turned and yelled down the hall. “He’s here!”

He waved me inside, into a room that turned out to be almost half of the building’s third floor. It was a dim cavern, kept in semidarkness by venetian blinds. From what I could see it was mostly open space. Soda cans and industrial-size bags of popcorn had accumulated in the corners, along with a yoga ball, stacks of colorfully illustrated rule books, and what appeared to be a functioning crossbow. It looked like the aftermath of a weekend party held by a band of improbably wealthy ten-year-olds. In fact, there was a man curled up under one desk in a puffy blue sleeping bag. A young woman in a tie-dyed dress and sandals was sitting against one wall, typing on a laptop, ignoring me, her blond hair done in elaborate braids.

While I waited for Matt to come back, I looked at a wall of framed magazine covers and Game of the Year awards. I went over to one of the computers, which showed what I thought at first was an animated movie of a space battle, but when I touched the mouse the camera panned around the scene, and I saw it was a functioning game, a fully realized environment navigable in three dimensions. I hadn’t been paying much attention to video games for a few years, not since I’d graduated from college. Did they turn into something totally different when I wasn’t looking?

I was born in 1969, which was the perfect age for everything having to do with video gaming. It meant I was eight when the Atari 2600 game console came out; eleven when Pac-Man came out; seventeen for The Legend of Zelda . Personal computers were introduced just as our brains were entering that first developmental ferment of early cognitive growth, just in time to scar us forever. In 1978, kids were getting called out of class in the middle of the morning. A woman from the principal’s office (whose name I never learned) quietly beckoned us out two at a time, alphabetically, and ushered us back in fifteen minutes later. When our turn came, I went with a boy named Shane. I was tingling a little bit just with the specialness of the moment, the interruption of routine. We were led down the hall to sit in one corner of the school secretary’s office in front of a boxy appliance that turned out to be a computer. It was new, a Commodore PET computer.

The PET’s casing was all one piece, monitor and keyboard and an embedded cassette tape drive forming a blunt, gnomic pyramid. It was alien, palpably expensive, and blindingly futuristic in a room that smelled of the mimeograph machine used to print handouts in a single color, a pale purple—a machine operated in exactly the same manner as when it was introduced in the 1890s, with a crank.

The lady sat us down and quietly walked away. Shane and I looked at each other. I don’t know what he felt, but there was a realization stirring inside me. They didn’t know what the machine was. They’d been given it, but they didn’t know how to use it. It didn’t do much. It didn’t understand swear words or regular English. It played a couple of games, Snake and Lunar Lander . After fifteen minutes she led us back to class and brought out the next two kids, who would also type swear words into it.

But it was probably the most generous and the most humble gesture I received from an adult in the sixteen-year duration of my schooling. The woman was simply leaving us alone with our future, the future she wouldn’t be part of. She didn’t know how to do it or what it was, but she was trying to give it to us.

As we grew, the medium grew. Arcade games boomed in the late seventies and eighties and gave rise to video-game arcades themselves, built in retrofitted department stores and storefront offices, making money in twenty-five-cent increments, floods of quarters warmed with adolescent body heat. These were the cooler, dumber cousins of the quiet, hardworking PET. Video games had the street swagger and the lowest-common-denominator glitz of pinball machines refracted through the seemingly ineradicable nerdiness of digital high tech.

I was older when I started going to arcades—eleven, maybe. I relaxed in the warm, booming darkness of the arcade, the wall of sound, and the warm air, smelling of sweat and teenage boys and electronics. The darkness was broken only by neon strips, mirrored disco balls, and the lighted change booth. Looking around the arcade was like seeing thirty Warner Bros. cartoons playing at once, shown ultrabright and overspeed.

The state of the technology meant characters were drawn on 8-by-12-pixel grids, a strangely potent, primitive scale. Dogs and mailmen and robots became luminous pictoglyphs hovering in the dark. The cursory, dashed-off feel of the stories seemed to have opened a vein of vivid whimsy in the minds of the programmers and engineers of this first wave. The same limitations threw games into weird, nonperspectival spaces. Games like Berzerk and Wizard of Wor took place in bright Escher space, where overhead and side views combine.

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)