“You seem to be all right—I mean you look well, too, Michael. I-Imust say I didn’t expect this.” Her hand swept around the room.

“What did you expect?” Sweat was on his face. Oh, the things that he had found again in this room did not stand up to Margaret.

“Michael, I need the baby things. The bassinet and the carriage.”

“I can see that Roger’s knocked you up. I’m giving you the benefit of the doubt, of course.”

She smiled, unthinkingly, despite the insult, trying to get past the moment, trying to get away. That smile meant to Lander that she thought infidelity was funny, a joke they could laugh about together. It pierced Lander like a red-hot poker.

“I can get the things from the garage.” She moved toward the door.

“Have you looked for them yet?” Show it to her. Show it to her and kill her.

“No, I was about to—”

“The bassinet and the carriage aren’t there. I put them in storage. The sparrows get in the garage and speckle everything. I’ll have them sent over.” No! Take her in the garage and show it to her. And kill her.

“Thank you, Michael. That would be very nice.”

“How are the kids?” His own voice sounded strange to him.

“Fine. They had a good Christmas.”

“Do they like Roger?”

“Yes, he’s good to them. They’d like to see you sometime. They ask about you. Are you moving? I saw the big truck in the driveway and I thought—”

“Is Roger’s bigger than mine?”

“What?”

He could not stop now. “You Goddamned slut.” He moved toward her. I must stop.

“Goodbye, Michael.” She moved sideways toward the door.

The pistol in his pocket was burning his hand. I must stop. It will be ruined. Dahlia said it is a privilege to watch you. Dahlia said Michael you were so strong today. Dahlia said Michael I love to do it for you. I was your first time, Margaret. No. The elastic left red marks on your hips. Don’t think. Dahlia will be home soon, home soon, home soon. Mustn’t—Click.

“I’m sorry I said that, Margaret. I shouldn’t have said it. It’s not true, and I’m sorry.”

She was still frightened. She wanted to go.

He could hold on a second longer. “Margaret, there’s something I’ve been meaning to send you. For you and Roger. Wait, wait. I’ve acted badly. It’s important to me that you’re not angry. I’ll be upset if you’re angry.”

“I’m not angry, Michael. I have to go. Are you seeing a doctor ?”

“Yes, yes. I’m all right. It was just a shock, seeing you.” His next words choked him, but he forced them out. “I’ve missed you and I just got disturbed. That’s all. Wait one second.” He walked quickly to the desk in his room, and when he came out she was going down the stairs. “Here, I want you to take these. Just take them and have a good time and don’t be mad.”

“All right, Michael. Goodbye now.” She took the envelope.

At the door, she stopped and turned to him again. She felt like telling him. She was not sure why. He ought to know. “Michael, I was sorry to hear about your friend Jergens.”

“What about Jergens?”

“He is the one who used to wake us up calling you in the middle of the night, isn’t he?”

“What about him?”

“He killed himself. Didn’t you see the paper? The first POW suicide, it said. He took some pills and pulled a plastic bag over his head,” she said. “I was sorry. I remembered how you talked to him on the telephone when he couldn’t sleep. Goodbye, Michael.” Her eyes were like nailheads, and she felt lighter and didn’t know why.

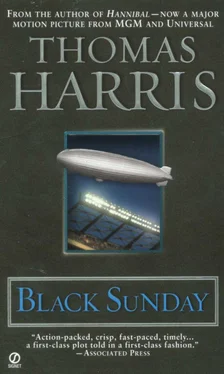

When she was three blocks away, waiting at the light, she opened the envelope Michael had given her. It contained two tickets to the Super Bowl.

As soon as Margaret left, Lander ran to the garage. The bottom was out of him. He began to work very rapidly, trying to stay above the thoughts rising like black water in his head. He eased the rented forklift forward, pushing the fork under the cradle that held the nacelle. He switched off the forklift and climbed out of the seat. He was concentrating on forklifts. He thought about all the forklifts he had seen in warehouses and on docks. He thought about the principles of hydraulic leverage. He walked outside and lowered the tailgate of the truck. He attached the sloping metal ramp to the rear of the truck. He thought about landing craft he had seen and the way their ramps were hinged. He thought desperately about loading ramps. He checked the street. Nobody was watching. It didn’t matter anyway. He jumped back on the forklift and raised the nacelle off the floor. Gently now. It was a delicate job. He had to think about it. He had to be very careful. He drove the forklift slowly up the loading ramp and into the back of the truck. The truck springs creaked as they took the weight. He lowered the fork bearing the nacelle, locked the brake, chocked the wheels firmly, and secured the nacelle and forklift in place with heavy rope. He thought about knots. He knew all about knots. He could tie twelve different knots. He must remember to put a sharp knife in the back of the truck. Dahlia could cut the ropes when the time came. She would not have time to fool with knots. Oh, Dahlia. Come home. I am drowning. He put the loading ramp and the duffle bag of small arms inside the truck and locked the tailgate. It was done.

He threw up in the garage. Mustn’t think. He walked to the liquor cabinet and took out a bottle of vodka. His stomach heaved up the vodka. The second time it stayed down. He took the pistol from his pocket and threw it behind the kitchen stove where he could not reach it. The bottle again, and again. Half of it was gone and it was running down his shirt front, running down his neck. The bottle again, and again. His head was swimming. I mustn’t throw up. Hold it down. He was crying. The vodka was hitting him now. He sat down on the kitchen floor. Two more weeks and I’ll be dead. Oh, thank God, I’ll be dead. Everybody else will be too. Where it’s quiet. And nothing ever is. Oh, God, it has been so long. Oh, God, it has been so long. Jergens, you were right to kill yourself. Jergens! He was yelling now. He was up and staggering to the back door. He was yelling out the back door. Cold rain was blowing in his face as he yelled out into the yard. Jergens, you were right! And the back steps were coming up at him, and he rolled off into the dead grass and snow, and lay faceup in the rain. A last thought, consciousness glimmering out. Water is a good conductor of heat. Witness a million engines and my heart cold upon this ground.

It was quite late when Dahlia set her suitcase down in the living room and called his name. She looked in the workshop and then climbed the stairs.

“Michael.” The lights were on and the house was cold. She was uneasy. “Michael.” She went into the kitchen.

The back door was open. She ran to it. When she saw him she thought he was dead. His face was white with a bluish tinge and his hair was plastered flat by the cold rain. She knelt beside him and felt his chest through the soggy shirt. His heart was beating. Kicking off her high-heeled shoes, she dragged him toward the door. She could feel the freezing ground through her stockings. Groaning with the effort, she dragged him up the stairs and into the kitchen. She jerked the blankets off the guest-room bed and spread them on the floor beside him, stripped the soggy clothes off him and rolled him in the blankets. She rubbed him with a rough towel, and she sat beside him in the ambulance on the way to the hospital. At daylight, his temperature was 105. He had viral pneumonia.

Читать дальше