“Enough for now,” said Naomi. She reached for her sake.

“Call me Ari,” said Arosteguy.

“Enough for now, Ari.” She drained the cup and poured herself more.

THE DOOR TO NATHAN’S basement bedroom opened a crack, letting in a slash of light that cut across his face, waking him, befuddled, still dreaming himself a child with his white underpants on his head to keep his wet hair from soaking the pillow, something he had worked out with his mother, who tended to remember he needed a bath just before bedtime. When he awoke, the underpants—worn and frayed, the elastic popping out everywhere around the waistband—were always miraculously gone and his hair was dry, just as it was now. And the unutterable sweetness of that dream suffused, in a bizarre, wholly inappropriate way, the sinister shadow that appeared at the entrance to the room, hesitated, then slid elastically over the door frame and the dressing table. When the shadow reached Nathan, it liquidly merged with a silhouette that was Roiphe, tiptoeing in comic fashion.

“Nathan? Are you awake?” The sweetness quickly leached away at the touch of Roiphe’s nasal voice, leaving a sourness tinged with anxiety, which, Nathan understood, was his default reaction to Roiphe.

“Not really,” said Nathan. “Do I have to be?”

“Well, get awake and grab your camera,” said Roiphe. “I was going to wait till we had some major prep time, but it’s happening now, so let’s take it at the flood.”

“Flood?”

Roiphe shook his head in mild exasperation. “It’s time to observe the nocturnal habits of an odd creature. Get up, boy.”

Nathan’s sense of being a boy in his childhood bed was palpably enhanced by his pajamas and slippers, which as an adult he never wore. The slippers were white Crillon hotel slippers bearing the elegant golden, foliate, and crowned letter C logo, given to him by Naomi, of course, who knew he’d be staying in places that did not hand out free slippers; the garden-variety striped flannel pajamas with the big white plastic buttons he had bought at the Hudson’s Bay department store, anticipating that he’d toss them once he was no longer a resident at the Roiphe Hostel. Just the thought of sleeping naked in that basement under that thin, clumped-up acrylic duvet provoked revulsion. And yet it was the pajamas and the slippers, the protective apparel, that transported him to a strange and unexpected place as he followed Roiphe through the darkened house, which sported sly, unexpected nightlights everywhere. Slithering in the sloppily fitting backless Crillon slippers up the teakwood staircase, clinging to the handrail of the wrought-iron balustrade—also foliate in a pseudo art nouveau style—Nathan listened to Roiphe whispering that the series of rooms on the third floor, which they were approaching, had been built “against code.” The trick had been to leave it unwalled and unfinished until after the final building-code inspections had been carried out, and then to have the rooms miraculously appear to the first buyers of the house in all their beautifully executed, dormered glory as “architectural workspace.” Said space now occupied solely by Chase Roiphe. But Nathan was also slithering in his childhood moccasin slippers, slithering downstairs by the light of the potent chromed-aluminum Eveready flashlights that he and his fragile, thin-limbed sister, Shelley, held, making their way before dawn to their living room, which was all but filled by an upright piano and a Christmas tree decorated with everything commercial and nothing Christian—candy canes, reindeer, elves, tinsel, cotton-batting snow, edible stars. There were presents of every size and shape under the tree, of course—the point of the whole exercise. Nathan had sent a SantaGram to the North Pole, and Santa had come through in the most satisfying way.

LATER, THEY SAT DOWNSTAIRS, with what Nathan thought was perverse appropriateness, in the kitchen. The granite-topped island, whose vast and immaculate surface was interrupted only by a stainless-steel offset double-bowl sink, provided a clinical workspace for what Roiphe, rocking pelvically, rhapsodically, on his spidery wrought-iron breakfast stool, called “our first strategic debrief.” Nathan sat beside him on a sister stool, not rocking, his laptop on the granite in front of them, scrolling through the photos he had taken over the last hour. The fourteen embedded digital clocks strewn around the room, from the MacBook Pro to the ice-maker in the Sub-Zero fridge, the Wolf stove, the Jenn-Air warming drawers, Nathan’s camera (which sat just beyond the laptop), to Roiphe’s own odd cheap plastic wristwatch, all indicated that the time was somewhere between 4:06 and 4:09 A.M.

“So you see what we’re up against here, son. What we’re working with.”

“Not really,” said Nathan. “Honestly, I’m kind of in shock. That’s really what I’m working with.”

Roiphe managed to work some rhythmical sympathetic nodding into his rocking. “Uh-huh, uh-huh, I can understand that. And that’s what we’re doing here, right now. Want some ice water? Maybe coffee? Anything?”

“No, thanks. I’m good.”

“‘I’m good’ is funny. Sounds funny to me. We never used to say that. We’d say ‘I’m fine. I’m all right.’ But they do say ‘I’m good’ these days. So what are we looking at here? What happened? What did you see? What did you shoot?”

“I’m having trouble believing what I’m looking at right now,” said Nathan, squirming a bit on the stool. Its floral-print plastic cushion was coming loose at the rear left edge, and he was half-consciously trying to slide it back into place with his buttocks.

“I think maybe you should just verbalize. Keep it simple and direct and we’ll get somewhere fast.” Roiphe was still nodding and rocking, but now with a fierce-eyed intensity that was unmistakably masturbatory, urging Nathan on towards some obscure epiphanic orgasm that he felt was completely beyond him. He decided to keep it simple and direct.

“Your daughter, Chase, was cutting bits of her flesh off with a nail clipper, putting those bits onto little children’s plastic toy plates, and then eating those bits of flesh using little children’s toy utensils.”

“Uh-huh. Uh-huh. And what do you think her state of mind was while she was doing this? Was she hurting herself ? Was she in pain? Was she punishing herself ?”

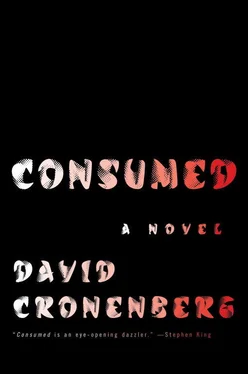

Nathan wondered if Roiphe was aware that he was recording their conversation through GarageBand on his MacBook. He had it running on Desktop 2, so the app was not visible (though only a three-finger swipe away), and it thus perhaps counted as semiconscious surreptitiousness. Like clocks, recording devices were everywhere embedded; everything was being recorded at every moment, like a huge, infernal Mac Time Machine backup system that created backups of backups regressing into infinity. Who would play these back? Who would pick among them like the survivor of a hideous bombing looking for the rags once worn by his dead and naked mother? He was not yet sure how much he wanted Nathan Math the character to feature in Consumed: The Collaboration , but at the very least his side of every exchange with the Roiphes—and who knew who else?—would provide context which might ultimately even have legal consequences, given the weirdness that was emerging from Roiphe’s life and practice.

Nathan was running his photos within Lightroom, which allowed him to easily manipulate their quality as he and Roiphe reviewed them. He could pull down seemingly burned-out highlights to reveal startling details of expression, and open up clogged shadows to reveal tormented gestures; later, he could play with them as photographic art, tweak them towards meaning that was not yet obvious, though he could not imagine including them in their chimerical book. The “Annals of Medicine” piece had more future reality to it, though it too was unstable, shimmering, flickering—morphing perhaps into a piece for “Annals of Psychopathology,” no pictures allowed. And in playing with the photos, he experienced once again the phenomenon of non-presence, the photographer’s non-authentic existence during the act of photographing; only in reviewing the photos did the event photographed emerge in experience, like the flowering precipitate caused when a crystal of sodium acetate was dropped into its supersaturated solution. But then the experience was moderated by the photo, the lens, the camera, the camera-eye’s response to the light—and that was what Nathan was reacting to now. He was not sure he had actually seen any of these events with his real eyes, a feeling sharpened by the clattering of the big camera’s shutter and mirror, which he could hear as he looked at the photos; the sound became part of his interpretation, even though Chase herself never seemed to react to it or notice it at all.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

![David Jagusson - Fesselspiele mit Meister David [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/486693/david-jagusson-fesselspiele-mit-meister-david-har-thumb.webp)