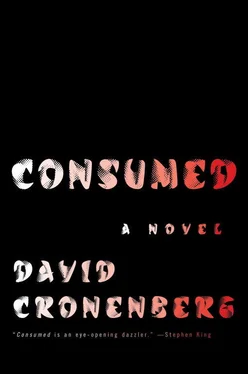

“Professor Matsuda, I will be seeing Monsieur Arosteguy alone. Completely alone.”

“Yes.”

“Should I be worried?”

Matsuda adjusted his glasses with both hands. “There are so many levels to that question.”

“The level that I’m concerned about is the physical safety level. Will I be in danger from the philosopher? I don’t mean philosophical danger, or emotional danger. I mean physical danger.” Matsuda seemed unable to answer. He just stared at Naomi, blinking as a small flock of birds swept over the pond. Naomi pushed. “Some French policemen consider him capable of murder.”

It was apparent now that Matsuda could not bear these words. There were beads of sweat on his forehead. He stood up. “Please give the philosopher Monsieur Arosteguy my regards when you see him.” He bowed, turned, and strode off along the verge of the pond, a briefcase, which Naomi had somehow not noticed before, held stiffly at his side, not swinging.

NAOMI STOOD IN A residential street in Western Tokyo that looked more like an alleyway than a street. Yukie had assured her that, yes, there were houses in Tokyo and they were much more common than, say, houses in Paris, some of them very large and luxurious, some of them miniature modernist jewels. But as her cab left her, picking its way gingerly past the bicycles, potted plants, baby strollers, plastic garbage cans, and random furniture lining the street, she could see that Arosteguy’s house was neither luxurious nor jewel-like.

It was after 8 P.M. and the light was fading fast. Naomi pulled out her camera—the compact Sony RX100 again; better to look like a tourist for now—and began snapping off shots in all directions. She steadied the camera against whatever wall or pole was handy to compensate for the low light levels and the resulting slow shutter speeds. The gathering twilight combined with the mercury-vapor street lamps and the incandescent light spilling from house windows made for pleasingly surreal 3D-feeling images. She could almost hear the little camera’s computers buzzing madly in their attempt to balance the color temperatures of the varied light sources.

After documenting the shop across the narrow street, its steamed-up windows displaying mysterious aluminum, ceramic, and glass containers, Naomi turned her attention to Arosteguy’s gray-stuccoed two-story house with its sad garden just inside the entrance. It was streaked with dirt and crumbling, its ironwork gate pocked with rust and its garden a rotting, garbage-strewn mess. There was some thin light showing through the second-floor windows, but the first floor was dark. After exhausting every imaging possibility she could think of, scrolling through her shots to see if anything jumped out at her, Naomi put the camera in her bag and crossed the street, trailing her roller behind her.

On the outer wall, just beside the open gate, a stainless-steel mailbox featured stenciled white numbers—“13-23”—on a blue rectangle. Another blue rectangle contained impenetrable white Japanese characters. Walking through the gate and into the courtyard, which was fitfully lit by stained orange garden lights built into its raw concrete walls, Naomi was tempted to take out her camera and start snapping again—so many wonderful depressing details expressing the decay of this man’s life (as the accompanying copy would have it)—but she resisted. There would be time.

Facing the sliding wooden doors, Naomi vainly tried to see through their narrow, full-length vertical panes of pebbled glass. She thought she saw a security camera in a hat-like galvanized steel housing above and to the right of the doors, but it proved to be an electricity meter. Electrical wiring crawled haphazardly all over the building’s stucco, many of the corroded screws and clamps barely hanging on. She looked for a buzzer or a doorbell, but there wasn’t one, so she knocked on the glass, which rattled at her touch. After a moment, a dim, watery light came on somewhere deep in the room beyond, there was a scuffle of locks, and the door slid open.

Arosteguy stood in the doorway, his face hidden in shadow, a large, imposing, shaggy presence. This surprised Naomi; from her YouTube experience of the philosopher, he was small and fastidious about his appearance. She wondered for a moment if this man at the door was someone else, or even if she had the wrong address, but after warily looking her up and down, he spoke, and the voice and the accent were Arosteguy’s.

“You’ve brought your suitcase. That is good.”

Naomi glanced down at her camera roller, nervous. “Oh, this? It’s my equipment roller. I keep my camera and flashes and things in it. I thought it’d be okay to bring it. We talked about photo shoots, documenting your life here…”

Arosteguy reached down and picked the roller up by its top handle. “Heavy. Heavy equipment.” He hunched his shoulder to move the roller out of Naomi’s way and slid the door open wider with his knee for her to enter ahead of him. “Take your shoes off and come in,” he said, assuming she would be oblivious of that protocol despite his stockinged feet and the presence of his own oxblood brogues sitting in the genkan just before the step up into the house.

Arosteguy served green tea to Naomi, who sat floor level in a dumpy beanbag chair in a generally dumpy small living room. The light remained as sickly as it had looked through the front-door panes, adding to Naomi’s tightening unease. Greasy sliding glass back doors opened out into darkness. Naomi could now see that he was haggard and unshaven, his long hair—gray with some black streaks still—unwashed and wild, his clothes rumpled and slept in. It all somehow made him even more attractive, and Naomi was aware that this, not fear, was the source of her unease.

“Thank you,” she said, taking the tea.

Arosteguy sat opposite her on a futon folded into a couch and sipped his own tea, cradling the cup as if for warmth. A fragrance, vaguely Japanese in character and not unpleasant, seemed to emanate from him. “And so, yes, you brought your camera. That’s good. You’ll want photos. I’ve taken some photos myself. Very strong photos.”

It was the last phrase that added intimidation, and perhaps now at last fear, to the established substratum of unease. Naomi had to work hard not to imagine this man, still trailing a fragrant effluvium, meticulously photographing his wife’s half-eaten head. Were some of those photos she found on the net posted by him, posted in defiance, perhaps, or perversity?

She had to hasten to fill the lapsed moment, almost stuttering. “Have you? Photos? Um, were they journalistic photos or art photos?”

Arosteguy laughed a ropey laugh. He lit a Japanese cigarette that he had some trouble shaking out of a pack beside him on the couch, then laughed some more, emitting short snorts of smoke towards her.

“I only smoke Japanese now. I want to become Japanese. I’ll never speak French again. Never. They say that Tolstoy learned classical Greek very quickly once he put his mind to it. I’m learning Japanese very quickly. Until then, I speak English or German. For philosophy, at least, you have to speak German. Perhaps I will make Japanese essential for contemporary Western philosophy. If I live long enough.”

Naomi was groping. “Photography has no language. Is that why you’re so interested in it?”

“I think you’ve seen some of my photographic work,” said Arosteguy. “You can tell me whether it’s journalistic or artistic. I myself think that it’s both.”

“I’ve seen your work?”

“On the internet. Those famous photos of my wife. I posted them from Todai, from the university.” Another small laugh, a phlegmless one this time. “They don’t know it yet.”

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

![David Jagusson - Fesselspiele mit Meister David [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/486693/david-jagusson-fesselspiele-mit-meister-david-har-thumb.webp)