Antiparos was the neighbouring smaller island to the west.

It felt strange to hear Bekim described in the present tense; as if he wasn’t dead at all. Of course, in this woman’s mind, he was still very much alive.

‘Bekim Develi. The Goulandris family. Tom Hanks. His wife, Rita Wilson, she is Greek. Everyone like it here because nobody knows they’re here. Is a big secret.’

I couldn’t help but wonder about that, given the alacrity with which Zoi had told me of their presence on the island.

‘Do you cook for him, too? Bekim, I mean.’

‘No. He say he very fussy. He doesn’t like Greek food. Only Greek wine. Just very plain English things. Eggs, bread, salad. I bring him these things but always he prepares his own food.’

It seemed strange to have a holiday home on a Greek island if you didn’t like Greek food; then again most English tourists in Greece seemed to subsist on a diet of hamburgers and chips.

‘I can cook for you if you like, Mr...?’

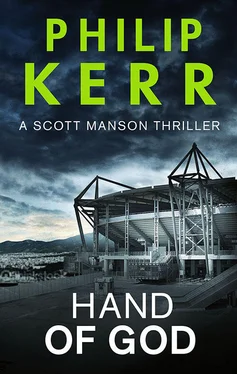

‘Manson. Scott Manson.’ I picked up a photograph on one of the kitchen shelves and showed it to her; it was a team photograph taken at the end of the last season when we’d just learned we’d made it to the fourth spot and had qualified for Champions League football. I couldn’t help but wonder what might have happened if we’d come fifth. Would Bekim still be alive? ‘That’s me there,’ I said.

‘Yes,’ she said, more reassured now than before. ‘That is you.’

‘I’ll probably go into town tonight and find something to eat in a local taverna,’ I said. ‘So there’s no need to trouble yourself.’

‘Is no trouble. I like to cook. But as you wish, mister.’

‘Otherwise I can make do with a plate of tinned spaghetti. Like Mr Develi.’

She pulled a face at the thought of that. ‘Ugh. I don’t know how he can eat things out of a tin.’

‘He sounds like a difficult man to work for,’ I said.

‘Mr Develi?’ Zoi frowned and shook her head. ‘He is a wonderful man,’ she said. ‘No one ever had a better person to work for than him. He is kind and generous like no one I ever met. Other people who know him will tell you this, too.’

‘Really? I thought you said he was very private here.’

‘He has friends on the island. Of course he does. There’s the artist lady in Sotires, who knows him best, I think. Mrs Yaros. She and Mr Develi are very good friends. She’s a sculptor. Lots of sculptors live on Paros. They used to come here for the fine marble but now all the best marble is gone, I think. I think maybe she know him better than anyone around here.’

‘I’d like to meet this Mrs Yaros. Do you think she’s at home?’

Zoi nodded. ‘I saw her this morning. In the supermarket.’

‘What’s her address?’

‘I don’t know the address. But her house is easy to find. You drive away from here, turn left, go for three miles, past old garage, turn right and her house is at the top of a steep hill. Is grey and white. There is a big blue gate. And sometimes a dog. The dog isn’t friendly, so you’d best wait in the car until she comes to fetch you.’

‘Thanks for the advice.’

I finished my coffee and then got back into the car. Even though I’d parked it in the shade the little Suzuki felt as hot as a crematorium. I switched on the air conditioning, started the engine and drove back down the track towards the garage. A few minutes later I was through the blue gate and driving up a steep, paved slope which had the little Suzuki straining to reach the top. But for the tip about the dog I might almost have got out and walked. The slope levelled out at the edge of a terraced garden and, above the sound of the engine, I heard what sounded like a dentist’s drill. For a moment I thought I might have got the wrong house. Then, in an open workshop/studio, I caught sight of a slight figure in a mechanic’s blue overalls, covered in a fine white dust. It was hard to make out if this was a man or a woman because of the protective mask he or she was wearing. I steered under the shade of a carport and waited for the dog or its owner, but when neither came I opened the car door cautiously and called out.

‘Mrs Yaros? Forgive me for dropping in on you like this. My name is Scott Manson. And I’m a friend of Bekim Develi.’

By the time I had walked to the workshop the figure in the overalls had switched off the compressed air cylinder that powered a tiny drill being used to fashion an impossibly beautiful spiral of marble that looked like a piece of material falling through the air, removed her mask and tossed a mane of blonde hair from one shoulder to the other.

I recognised the woman immediately. It was Svetlana Yaroshinskaya, better known to me as Valentina.

‘What on earth are you doing here? I don’t understand. This is private property. Did Bekim tell you how to find me?’

Somehow the woman managed to look more beautiful in her dusty overalls, although that could have had something to do with the fact that she had already unbuttoned them to reveal her generous cleavage. I opened my mouth to account for my presence but she wasn’t yet in the mood for explanations.

‘I must say that was very unkind of him, to say where I was. You can tell him from me: I’m very angry. He’s betrayed my trust.’

The pink sandals she was wearing and her painted toenails were about the only concessions she’d made to her own femininity; that and the diamond stud I could see glinting in her belly button.

‘It wasn’t Bekim who told me how to find you,’ I said. ‘It was Zoi. His housekeeper.’

‘How did you even know I was here?’

‘I didn’t. I came to see a Mrs Yaros. And instead it’s you, Valentina. Frankly, I’m as surprised as you are. I had assumed Mrs Yaros was a Greek. I mean, it sounds Greek.’

She nodded. ‘That’s how I like it. Yaros is short for Yaroshinskaya — my real name. And please don’t call me Valentina. Not on Paros. I’m never Valentina when I’m here. My first name is Svetlana.’

‘All right.’ I raised my hands in surrender. ‘No problem.’

‘So why are you here?’

Like Zoi, Valentina clearly had no idea that Bekim Develi was even dead. For a moment I considered telling her I’d come to buy a sculpture, to spare her feelings a little, but in her dusty overalls she looked tough enough to hear what I had to say without a lengthy team talk.

‘I’m here because Bekim is dead,’ I said, bluntly. ‘Last Tuesday night, during a football game against Olympiacos, he collapsed and died on the pitch in front of twenty-five thousand people.’

‘Oh my God,’ she said. ‘Poor Bekim. I didn’t know.’

‘So I gather.’

‘You’d better come into the house.’

She led the way around an odd-shaped swimming pool to a small back door, and stepped over a sleeping dog.

‘Zoi told me he was fierce,’ I said, hesitating.

‘He used to be. But he’s too old to offer much in the way of defence now.’

‘I know the feeling.’

I followed her into a sparsely furnished house that was more of a museum to work I presumed must be her own. We went through a drawing room and into the kitchen where she lit a cigarette and started to make Greek coffee. Next to the cooker was a photograph of Svetlana in St Petersburg standing next to an enormous equestrian statue of Peter the Great. I’d seen it from the bus on the team’s pre-season tour of Russia; at the time the tour had seemed like a disaster but of course that was before I knew what a real football disaster felt like.

‘What was it?’ she asked. ‘A heart attack, I suppose.’

‘Something like that. We’re still awaiting the autopsy, I’m afraid. Nothing in Athens moves quickly, it seems. Especially when everyone seems to be on strike.’

Читать дальше