The other bedroom was much more spacious. It held four single beds with bare mattresses, giving Stevie the impression of a school dormitory on the last day of term. Unlike the smaller room, this one had an ensuite bathroom and a large in-built robe.

From a locked window Stevie had a good view of Mrs Hardegan’s neat back garden. A car pulled up outside her house. Lights flicked off and a man climbed out. It might be Fowler returning to ask Mrs Hardegan more questions, she thought, until she saw the man take a key from his pocket and let himself in through the front door.

The wind picked up in an instant and whipped at the trees in the surrounding gardens. In the street below, the patrol car’s door blew shut. The crime scene tech wrestled with his overall hood, but soon gave up, dashing to the white incident van as the first heavy drops of rain fell. Lights went on in the parked police cars as officers returned to exchange information gleaned from canvassing the neighbours.

Stevie felt as detached from the goings on below as if she were viewing it all from a CCTV monitor. The grey road gradually turned black, yet she could hear no sound of the storm, no hammering of the rain on the roof, rattling window frames or whooshes of wind in the eaves. In this room everything remained silent and still.

A sudden draft blew the heavy bedroom door shut. She drew a breath, whirled around and moved quickly. It was time to leave—the last thing she needed was for someone to come up and investigate the noise.

But when she reached for the doorhandle, there was nothing there. The handle was missing. She was trapped. (Image 3.1)

Image 3.1

CHAPTER FOUR

Lilly Hardegan turned off her TV and leaned back in the chair with the lacy armrests, pausing for a moment to listen to the drumming of the rain on the orange tiles of her roof. Through her open window the metallic smell of fresh rain on bitumen gusted in. Forcing herself to try to relax and enjoy the scent, she attempted to block out today’s disturbing events, closed her eyes and began to compose the letter she would never write to a person who would never be able to read it.

When she was writing in her head, she saw the words as clearly as if they were printed on a blackboard. But when she tried to say them aloud, it was as if the board had become coated with butter, and the words slid from it and flew around the room and all she had to catch them with was a large-holed net.

She began to compose, leaning back in her chair, fingers of each hand touching, here’s the church here’s the steeple, like the childhood game.

My Dear ... she began, setting the letter out in her head as if it were on a page. I trust this finds you...

A noise from the front of the house disturbed the flow of words. Surely the police wouldn’t be calling on her again when they knew she had so little to tell? She dimmed the table lamp and prised open the venetians. The Pavels’ house was lit like the Gloucester Park trots. The police were still there: she could see silhouettes in the cars, sheltering from the rain, and an officer standing on the front porch, but it had been a while since she’d seen anyone in the street.

Her body tensed. She continued to strain for alien sounds, one hand creeping down the gap between the side of her chair and the wall under the window. The carved texture of the samurai sword’s handle was a comfort, despite the weakness of her grip upon it.

When no more strange sounds seemed forthcoming, she let go of the sword and sank back into her chair. Sometimes she relished the idea of a fight, a chance to get even, with whom or what she still did not rightly know.

There had to be someone, there always was.

My Dear, I hope this finds you in a better state than when we last met

There it was again, a distinct thump, the sound of the front door closing. The passageway light clicked and shone under the door of her room—her sight and hearing were as acute as they’d ever been. The floorboards creaked more softly than usual, as if the person was treading on the tips of his toes, a sneaking teenager home well after curfew. Only two people had keys to the front door, and Skye said she was going home after her last visit. It could only be him.

Oh God, him.

Perhaps if she pretended to be asleep he would go away.

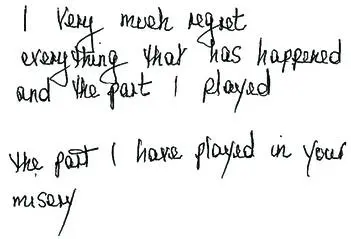

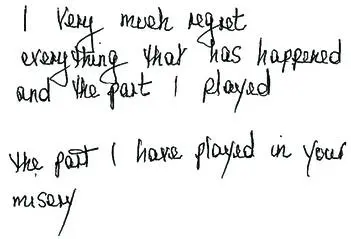

I very much regret everything that has happened and the part I have played in your misery

No, too syrupy, too sentimental. Not like you at all, Lilly, you can’t write that nonsense. Too much too soon; get back to that part later.

The door of the room announced his entrance with a slow moan. She ceased her composing as if, like an EEG, he might sense the activity in her brain. She kept very still in her chair, her eyes closed, keeping her breathing firm and even. His footsteps were softer than usual, as if he were trying to keep silent. A silent little mouse creeping across the lino, scritch scritchity scritch.

A shadow flickered through the red of her closed eyes. She willed her lids to remain steady and not betray her with vibrations. Her ears strained for the sound of his movement. The shadow stilled; he was very close now.

A feeling of dark warmth descended upon her from above.

‘Bloody Japs Bloody Japs!’ the parrot squawked.

Her heart gave an extra thud, her eyes shot open and she sat bolt upright in her chair. ‘You, boy—shock!’

He leapt back as if he’d been stung, clutching a green velvet cushion to his chest. ‘Christ, Moth, I thought you were asleep. I was just fixing your cushion, wanted to make you more comfortable.’

‘Doesn’t need fixing. Fine.’ In hospital she’d overheard the nurses joke about giving a troublesome patient the ‘Tontine treatment’. It didn’t seem funny now.

‘Well you shouldn’t leave it on the floor, it’ll get dirty,’ he said, frisbeeing the cushion onto the bed. He turned to the parrot. ‘And as for you, it’s about bloody time you fell off the perch.’ He tossed a blanket over the cage and made it rock. The parrot let out a final curse and fell silent.

Too vain for glasses, Ralph peered closely at her face. ‘God, Moth, you’re as white as a sheet, are you alright?’

‘Of course we’re alright, just a shock, you shouldn’t call at this time of night, tired, worried, must go to bed...’

‘It’s not late; it’s not even six o’clock. I’m here because the police called me. They said you were upset, said the Pavels have gone missing—does that mean the cops finally got round to checking up on them? I rang them several times you know, like you asked, but I think they thought I was some kind of crank. So what’s happened—no sign of the Pavels at all?’

She shook her head; it was so much easier.

‘I’ll make you a cup of tea.’

She didn’t want a cup of tea; she wanted to go to bed.

‘So ... what exactly did you tell the police?’ he asked as he bustled about the kitchenette. People often remarked upon her son’s resemblance to Sir Richard Branson—tousled grey hair and neatly trimmed goatee beard—and it was an image he seemed determined to cultivate, even adopting a similar dress style to the multi-billionaire. There weren’t many engagements grand enough to get him out of those bright figure-hugging shirts and designer jeans and into a suit. He probably wouldn’t even wear a suit to his mother’s funeral, she thought without sentiment. His ersatz Branson image had won and lost him three wives quicker than the real Branson could polish one of his jets.

Читать дальше