By now I was starting to guess which one of the two people in the room to whose advantage this job really was; and it didn’t look like it was going to be me.

“It’s been a while since anyone described me like that.”

“Really? As I recall, it was only last year that you were being offered up to the various guests at an international criminal police conference as Berlin’s answer to Sherlock Holmes. Or had you forgotten that speech you gave at the Villa Minoux? The one State Secretary Gutterer helped you to write.”

“As a matter of fact I had forgotten about that. I’d also formed the impression that that would be the last place Dr. Gutterer’s exaggerations regarding my abilities as a policeman would actually be taken seriously.”

“Did you, by God?” Goebbels laughed harshly. “Well, you’d be wrong. Any lingering doubts we might have had about your unique talents were removed when you managed to unfuck things so well at Katyn. I wasn’t wrong about you, Gunther. I realize we might have had one or two differences back there. I may even have left you in an awkward situation. But you’re a good man in a tight spot. And that’s what I’m in right now.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” I said with very little sincerity. Too little for a man with ears that were so carefully tuned to meaning, like the Mahatma’s.

He picked a tiny piece of thread off the trouser of his suit and dropped it onto the thick carpet, as if it had been me.

“Oh, I know you’re not a Nazi. I’ve read your Gestapo file — which, by the way, is as thick as a DeMille screenplay and probably just as entertaining. Frankly, if you were a Nazi you’d be held in rather better odor at RSHA headquarters and then you’d be no fucking good to me. The fact is I want this matter handled off the books. Which means to say I certainly don’t want bastards like Himmler and Kaltenbrunner finding out about it. This is a private matter. Do I make myself clear?”

“Quite clear.”

“Nevertheless they will try to find out what we’re doing. They can tell themselves all they like that it’s in the country’s best interests to know the private affairs of everyone in government. But it’s not. It’s in their best interest to get the dirt on everyone so they can use that to cement their own positions with the leader. Not that there’s any actual wrongdoing here, you understand. It’s just that they might easily imply that there is. Insinuation. Rumor. Gossip. Blackmail. That’s second nature to people like Müller and Kaltenbrunner. You may not be able to tell them to go to hell, exactly, but I’m confident that you’re the kind of fellow who can outfox them. With total discretion. Which is also why I’m prepared to pay you, out of my own pocket. How does a hundred reichsmarks a day sound?”

“Frankly? It sounds much too good to be true. Which is a habit of yours, after all.”

Goebbels frowned, as if he were unable to decide if I was being insolent or not. “What did you say?”

“You heard me. You’ll forgive me, sir, but in the event that I do end up working for you, then I have to be straight. Believe me, if this job does require the discretion you say it does, then you wouldn’t want it any other way. I never yet met a client who wanted me to put some syrup on top of a piece of hard cheese.”

“Yes,” he said uncertainly. And then with greater certainty, he added, “Yes, you’re right. I’m not used to people being straight with me, that’s all. Truth is in rather short supply in this day and age — when you have to rely on German civil servants. But then even the British have become experts in twisting the facts. Their reports of a night raid on the city of Dresden were a triumph of lies and obfuscation. You would think that there had been not one civilian casualty, that they bombed this city without a single civilian casualty. But that’s another matter. Thank you for the lesson in pragmatism. And since they do say that money talks, then perhaps it might be best if I were to pay you in advance.”

Goebbels put his hand inside his jacket and removed a soft leather wallet from which he proceeded to count five one-hundred-mark notes onto the table in front of us. I left the money there, for the moment. I was going to take the money, of course, but I still had my pride to take care of first; this residual feeling of my own dignity — which was not much more than a small shard of self-respect — was going to need some careful last-minute handling.

“Why don’t you tell me what the problem is and then I’ll tell you what can be done?”

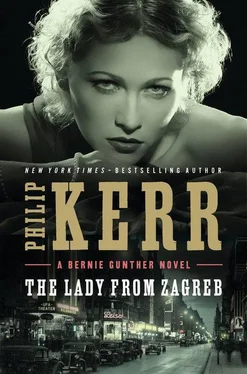

Goebbels shrugged. “As you wish.” He paused and then lit a cigarette. “I take it you’ve heard of Dalia Dresner.”

I nodded. Everyone in Germany had heard of Dalia Dresner. And if they hadn’t they’d certainly heard of The Saint That Never Was , one of the more sensational films in which she’d starred. Dalia Dresner was one of UFA-Babelsberg’s biggest film stars.

“I want her to be in Siebenkäs , my next picture for UFA. Based on the classic novel by Jean Paul, Married Life, Death, and Wedding of Siebenkäs, Poor Man’s Lawyer . Have you read it?”

“I haven’t, no. But I can see why you felt you had to change the title.”

“She’s perfect for the leading role of Natalie. I know it, she knows it, the director — Veit Harlan — knows it. The trouble is she won’t do it. At least she won’t until her mind has been put at rest about her father, with whom she appears to have lost contact. I believe they’ve been estranged for a long time, but her mother died quite recently and she’s decided she wants to make contact with him again. It’s a fairly typical story of our age, really. Anyway, she insists she needs a detective to help her find him. And since it’s Dalia Dresner, it can’t be just any detective. He has to be the best. And until she speaks to such a man and he does whatever it is that she wants him to do, it’s clear that her mind is going to be on other things than the making of this motion picture.”

“And you don’t want the Gestapo doing it.”

“Correct.”

“May I ask why?”

“I really don’t see that it’s any of your damn business.”

“And it can certainly stay that way. Frankly the less I know about your personal affairs the better I’ll feel. I certainly didn’t ask for this job. I didn’t ask to come here and be offered an opportunity for profit and advantage. If I was interested in either of those things, then by your own admission I wouldn’t be sitting beside you on this sofa. But I won’t work for you with a patch over one eye and one hand tied behind my back. If I am going to outfox the likes of Kaltenbrunner and Müller, then I can’t be treated like your poodle, Herr Doctor. That’s not how foxes operate.”

“You’re right. And I have to trust someone. Recent events have taken their toll on my health and I was obliged to cancel a badly needed holiday. This whole affair isn’t helping me, either. I should get myself in shape but I can see no possibility of that happening. Frankly it’s all left me feeling rather depressed.”

He crossed his legs and then nervously hugged his right knee toward him so that I had a good view of his famously deformed right foot.

“Do you have a sweetheart, Herr Gunther?”

“There’s a girl I see, sometimes.”

“Tell me about her.”

“Her name is Kirsten Handlöser and she’s a schoolteacher at the Fichte Gymnasium on Emser Strasse.”

“And are you in love with her?”

“No. I don’t think so. But lately we’ve become quite close.”

“But you’ve been in love, Herr Gunther?”

“Oh, yes.”

“And what was your opinion of being in love?”

“Being in love is like being on a cruise, I think. It’s not so bad if you’re sailing on a smooth sea. But when things start to get rough, it’s easy to start feeling lousy. In fact it’s amazing how quickly that can happen.”

Читать дальше