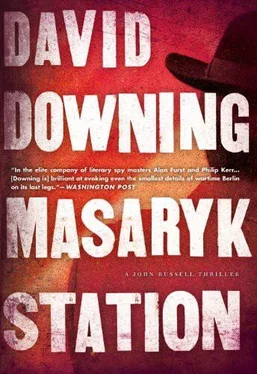

David Downing - Masaryk Station

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Downing - Masaryk Station» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Soho Press, Жанр: Шпионский детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Masaryk Station

- Автор:

- Издательство:Soho Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:9781616952228

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Masaryk Station: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Masaryk Station»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Masaryk Station — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Masaryk Station», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Walking back to his office, Strohm found himself wondering how the Western allies would react. So far, the messages had mostly been mixed, especially from the Americans. Their commander in Berlin, General Clay, seemed only too happy to pick up a gauntlet, but his superiors in Washington were obviously divided, with many openly voicing their unwillingness to fight another war for half a ruined city. If they were shown a graceful way out, Strohm thought, then they might really leave. And if they did, the Russians would feel more secure, and might eventually depart themselves, leaving their German comrades free to build their own version of socialism.

Improbable perhaps, but surely possible.

Back in his office he spent the next two hours dreaming up reasons for future interruptions. The Western authorities would know what was really happening, but they had to be given scope to pretend.

At lunch, Strohm shared a table with Trenkel and one of the more pro-Soviet deputies, a middle-aged Dresdener named Hadewicz who had spent the war in Moscow, but had worked on the railways in his youth, and distinguished himself in the anti-Nazi struggles of the early ’30s. Hadewicz had the latest Cominform bulletin with him, which gave Strohm the opportunity to ask them both what they felt about the rumoured disputes between the Russians and the Yugoslavs.

Hadewicz was dismissive-it would soon blow over-while Trenkel just shrugged, as if uninterested.

‘But think,’ Strohm persisted, ‘if Moscow and Belgrade can reach an agreement on each pursuing their own course in a comradely way, then so can Moscow and Berlin.’

Hadewicz just shook his head, and Trenkel flashed Strohm a warning glance. Strohm took the hint and changed the subject, but the conversation, or lack of it, haunted him for most of the afternoon. Walking to the Elisabeth Hospital later, where Annaliese would be nearing the end of her shift, he realised that the number of comrades with whom he could share a frank conversation had shrunk to almost zero-even those whom he knew shared his views found it safer to say nothing these days. The only person he could really talk to was his friend John Russell, and that was in spite of their political differences. Russell had turned his back on the Party more than twenty years earlier, but their analyses of what made the world tick were similar, and they didn’t have to look over their own or each other’s shoulder. All of which made for much more productive conversations than those Strohm endured with his KPD comrades.

Russell, however, was away, and there was no one else. Strohm loved Annaliese dearly, and her time in an American camp had made her more willing than most Berliners to give the Soviets and their KPD allies the benefit of the doubt, but talk of ideologies bored her.

He was, Strohm thought, remembering the phrase of a long-dead comrade, suffering from political indigestion. Maybe he should just stopping eating contrary ideas, like the ones in the pamphlet he was reading at home, which was an extract from Arthur Koestler’s ‘The Yogi and the Commissar’. Koestler was also an ex-Communist, and some of his arguments were hard to refute. But even if he was right, and Stalinism was the antithesis of all Marx had intended, what practical relevance did such thoughts have? They were where they were. Both in power and not in power, neither wholly disciples nor wholly slaves. They were struggling with the art of the possible.

Strohm turned off the canal towards the hospital entrance. As always, the thought of seeing Annaliese cheered him up. He had met her in Thomas Schade’s garden, and been smitten at first sight by her smile. They had both been invited to a family picnic, he by Russell, who had once been married to Schade’s late sister, she by Russell’s actress wife Effi, who had met and befriended her during the war. Schade was a bourgeois businessman and SPD supporter, but a decent man according to John, and Strohm had seen nothing to contradict that assessment. If all the Social Democrats were like Thomas, then half their problems would be solved.

He saw Annaliese the moment he passed through the doors. She and Effi were sitting in the patient waiting area, sharing something that made them both laugh. Annaliese jumped up when she saw Strohm, and enfolded him in a happy embrace. Effi followed suit, with her usual spontaneous warmth.

‘I just dropped in my way home,’ she told him. ‘Mostly to invite the two of you to Thomas’s house for lunch on Sunday week. He doesn’t trust the post anymore, and he didn’t dare ring you at work, in case someone listened in and thought you were plotting with the SPD.’

Strohm smiled. ‘As if. And we’d love to come, wouldn’t we?’ he asked Annaliese.

‘I’ve already accepted.’

‘And you can bring us up-to-date on Soviet intentions,’ Effi said, tongue in cheek. She liked Strohm, but he was sometimes too serious for words.

‘Of course. Will John be there?’

She shook her head. ‘Not as far as I know. He’s still in Trieste.’

‘What’s he doing down there?’

‘Researching a story on Nazi escape routes. Or so he claims. Every letter he sends me, he boasts about the beautiful weather. He keeps saying he’ll be back in a week or so …’ She changed tack. ‘Gerhard, I went to Sonja Strehl’s funeral on Tuesday, and there were all sorts of rumours doing the rounds. About how she died, I mean. You haven’t heard anything?’

‘No.’

‘I just wondered. She wasn’t exactly a friend, but I knew her for a long time, and I liked her.’

‘I’ll keep my ears open,’ Strohm promised. ‘But don’t expect too much. The last rumour I heard was about a missing coal train, which someone claimed the French had taken back to France. He might have been right-we still haven’t found it.’

At the villa above Trieste, Thursday proved depressingly similar to previous days. Perhaps even less entertaining, as Kuznakov and his interrogators were each growing increasingly irritated with the other’s refusal to give way. Dempsey and Farquhar-Smith wouldn’t move the Russian westwards until he’d proved he had something to give; and Kuznakov refused to offer anything tangible until he was safe, as he put it, in American territory. Trieste, though nominally under joint control, was apparently too close to Yugoslavia to qualify. ‘Full of MGB,’ Kuznakov insisted, with almost a hint of pride. He was more than ready to talk about life in the Soviet Union, and here his script seemed somewhat inconsistent, mixing fervent denunciations of communism with occasional, almost compulsive, mentions of Soviet achievements. And throughout it all Kuznakov puffed away on his dreadful cigarettes, of which he seemed to have an endless supply.

The only excitement of the day came late, when a vehicle was suddenly heard entering the compound. This time Kuznakov did look alarmed, and so did Farquhar-Smith. ‘It’s the CIA guy,’ Dempsey told them, ‘I forgot to tell you he was coming. It’s Russell here he wants to see.’

‘What for?’ Russell asked, heart sinking.

‘He’ll fill you in. We might as well wrap this up for today.’ Dempsey went to the door, summoned a soldier to take Kuznakov back to his room, and disappeared. A minute later he was back. ‘The Colonel’ll see you on the terrace,’ he told Russell.

The man in question was tall, grey-haired, probably in his early forties. He was wearing civilian clothes-quite a smart suit, in fact. He rose from a wrought-iron chair, offered Russell a hand, and introduced himself as, ‘Bob Crowell, CIA.’

The terrace was at the side of the villa, overlooking a steep drop, and with a distant view of the sea through the pines.

As Russell sat down, a soldier appeared with two bottles of beer. ‘If you don’t want one, I’ll drink both,’ Crowell told him. Despite being middle-aged, he had the air of a grown-up kid.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Masaryk Station»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Masaryk Station» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Masaryk Station» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.