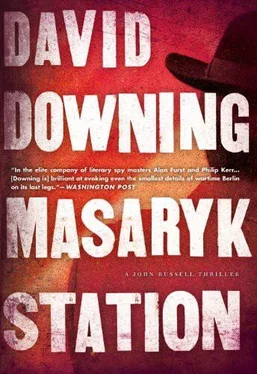

David Downing - Masaryk Station

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Downing - Masaryk Station» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Soho Press, Жанр: Шпионский детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Masaryk Station

- Автор:

- Издательство:Soho Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:9781616952228

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Masaryk Station: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Masaryk Station»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Masaryk Station — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Masaryk Station», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘No, you must keep it,’ Marohn told him.

‘But I don’t need a car,’ Strohm protested.

‘It’s not a matter of need; it’s a token of respect for the position you hold. All cadres above a certain level are to be allocated personal vehicles, and refusing to accept one will be interpreted as dissent. Understood?’

Strohm nodded.

On his way home he picked up a paper, but there was no news from Aue. The Soviets would keep this one quiet, he thought.

Annaliese knew him well enough not to be over-delighted with the car, simply noting that after the baby was born, they could take him or her out to the country. Strohm just grunted-on the way home from work he’d been wondering how to get rid of it, but all he’d come up with was hiding the damn thing away in a garage and throwing out the key.

As he got off the train at Zoo Station, Russell wondered whether he should make an effort to disguise himself. Some workingman’s clothes perhaps, or a pair of spectacles. But he hadn’t, and it was too late now. He pulled his hat down another centimetre and walked on towards Carmer Strasse.

Reaching the end five minutes later, he saw a couple of pedestrians and several parked cars, but neither of the former were loitering and all of the latter looked familiar. As he neared their building one of the neighbours emerged, saw him, and raised a hand in greeting before walking off in the other direction. If Beria’s men were lurking in the stairwell, they were well-concealed.

The stairwell was empty. He listened outside their door for a few moments, then rapped on it. No one answered, which seemed a good sign until he put himself in their position. Why would they?

He had tried to leave the new gun with Effi, but she had insisted he take it. ‘If they’re after us,’ she had said, ‘then they’ll be waiting for you.’

Well, were they? Russell took out the gun, turned the key, and pushed the door all the way open. There were no Russians on the sofa, and none in the bath. Everything looked exactly as they’d left it.

It was half-past two P.M.; he had half an hour to wait. He spent it by the window, eyes on the street and ears cocked for feet on the stairs. After an hour he reluctantly accepted that Shchepkin wasn’t going to ring, then belatedly checked that the phone was working. It was.

He locked the flat back up, and showed the same caution departing that he had on arrival. At a bank on Hardenberg Strasse he joined the queue for changing currency and eventually took possession of sixty new Deutschmarks. After walking back to Zoo Station, he spent the half-hour waiting in the buffet for the Wannsee train, and reading the local British newspaper. All the good news was on the front page-two days earlier, Foreign Secretary Bevin had told the world the British wouldn’t leave Berlin ‘under any circumstances’. The Americans had not yet given any such assurance, but that didn’t worry Russell. The steady stream of C-47s skimming the Wilmersdorf skyline seemed a lot more compelling than any words.

Strohm had been anticipating the radio programme for most of the day. The Hungarian Arthur Koestler had been a member of the Party in the 1930s, and Strohm had a vague memory of seeing him at a KPD meeting in the pre-Hitler years. He had worked for the Comintern in France, and as a journalist in Spain, before disillusionment caught up with him, and caused him to write the novel which RIAS had dramatized for that evening’s broadcast, Darkness at Noon .

Strohm had heard a lot about the book, but was still unprepared for the impact it had on him. He already knew it concerned a fictional Bolshevik named Rubashov, whom Stalin had turned on and imprisoned. The man’s philosophising proved fairly predictable-it was more his memories that undid Strohm. Little Loewy, the Party secretary who hanged himself, was Rubashov’s Stefan Utermann. In Darkness at Noon , the Bolshevik Rubashov journeyed from Moscow to Antwerp, and ordered Loewy to sacrifice comrades and conscience for the greater good of the Soviet Union. He had travelled the much shorter distance from Hallesches Ufer to Rummelsburg, and done exactly the same.

Strohm thought of Harald Gebauer up in Wedding, as he often did at such moments. That usually reassured him, but not this time. Harald’s criticism of the Party was implicit, because it came from the heart, and he would probably pass unnoticed for longer than those more cerebrally-gifted comrades whose critiques were spoken or written. But eventually someone would notice, and be all the angrier when they realised how long it had taken. And then someone else would discover that Strohm had known the man for years, and might be prevailed on to show him the error of his ways. The error of believing in mankind.

The play was still underway, but Strohm was caught by this glimpse into his future: Gerhard Strohm, closer of doors, firer of metaphorical bullets. Confiscator of dreams.

Once Rosa had fallen asleep, Russell and Effi discussed how long they could afford to wait for Shchepkin. They had agreed to give him until Tuesday, but how much longer than that? There was no easy answer. The moment they made the film public, their bargaining power would be finished, but so, they hoped, would be Beria’s career. At that point the MGB chief would have nothing to lose, but, unless Josef Stalin was completely impervious to world opinion, he and his country did. But would Uncle Joe act quickly enough, and kill Beria before a vengeful Beria succeeded in killing them? Even if Stalin did move promptly, the chances were still good that Russell’s role in the atomic business-not to mention his concealing of the film from his CIC bosses-would reach the light of day. Broadcasting proof of Beria’s infamy might bring justice for Sonja, her sister, and all the other women the man had probably raped or killed, and it might even lead to a diminishing of Soviet cruelty at home and abroad, but it wouldn’t do much for Russell and Effi.

Waiting, though, would get riskier by the day. If Shchepkin was in the Lyubyanka, then literally hundreds of MGB agents would be scouring Berlin for them and their copy of the film.

‘A few more days,’ Effi suggested. ‘Until Thursday. We can take it to the Americans on Friday morning.’

‘I’m not so sure,’ Russell argued. ‘I wish we’d made more copies. I’d feel a lot happier if we had a dozen to distribute. Then we’d know it couldn’t be suppressed.’

‘Why would the Americans suppress it?’

‘Think about it. If we can blackmail Beria with it, then so can they.’

Annaliese was on nights that week, and Strohm was alone when the phone rang late that evening. It was Uli Trenkel from the office, and he sounded more than a little drunk.

‘Have you heard?’ he asked excitedly.

‘Heard what?’

‘The Yugoslavs. They’ve been kicked out of the Cominform.’

‘What?!’

‘I’ve seen tomorrow’s Telegraf . The headline reads “Tito breaks with Stalin; Tito accused of Trotskyism”.’

‘But that …’ Strohm was lost for words.

‘Absurd. Isn’t it? But there’s nothing we can do.’ Trenkel prattled on, until Strohm abruptly ended the call for both their sakes. He poured himself a glass of payok whisky and went to stand by the open window. It was a chilly night, the sky full of stars.

So that was it, he thought. He had always imagined their first years in power as years of trial and error, the way they had been in Russia. An experimental journey, in which they all learnt from their mistakes. But now he knew different. There would be none of that in Germany, or anywhere else in eastern Europe. Wherever the Soviets were in control, their journey was being re-run. And if they hadn’t learnt from their mistakes, then those condemned to repeat them wouldn’t be allowed to either.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Masaryk Station»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Masaryk Station» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Masaryk Station» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.