“Correct.”

“You want to come back there with us, and show us where you threw it in the garbage?”

“Sure,” Coombs said, and got off the stool, and spat, and then led them around to the rear side of the hot-dog stand. “Right there,” he said, pointing. “In one of them garbage cans.”

“You carried that little tiny piece of the photograph out back here, and you lifted the lid of the garbage can and dropped it in, is that right?”

“Correct.”

“Show us how you did it,” Brown said.

Coombs looked at him curiously. Then he shrugged, pinched an imaginary photograph segment between his thumb and forefinger, carried it to the nearest garbage can, lifted the lid, deposited the non-existent scrap inside the can, covered the can, turned to the cops, and said, “Like that. That’s how I done it.”

“You’re lying,” Brown said flatly.

Neither of the two detectives, of course, knew whether or not Coombs was lying, nor had their little charade with the garbage can proved a damn thing. But public relations has a lot to do with criminal investigation and detection. There is not a red-blooded citizen of the US of A who does not know through constant exposure to television programs and motion pictures that cops are always asking trick questions and doing trick things to trap a person in a lie. Coombs had seen his share of movies and television shows, and he knew now, knew with heart-stopping, faceblanching, teeth-jarring certainty that he had done something wrong when he walked over to the garbage can, and lifted the lid, and dropped in the imaginary photo scrap, something that had instantly told these two shrewd investigators that he was lying.

“Lying?” he said. “Me? Lying?” He tried to spit again, but his throat muscles wouldn’t respond, and he almost choked, and then began coughing violently.

“You want to come along with us?” Carella said, sternly and pompously, and in his most legal-sounding voice.

“Wh... wh... wh...?” Coombs said, and coughed again, his face turning purple, and then put one hand flat against the rear wall of the hot-dog stand, head bent, and leaned against it, and tried to catch his breath and recover his wits. They had him cold, he knew, but he couldn’t figure what the charge would be, and he tried to buy time now while the big black cop reached into his back pocket and pulled out a pair of handcuffs with vicious-looking sawtooth edges — oh Jesus, Coombs thought, I am busted. But for what?

“What’s the crime,” he said, “the charge,” he said, “what’s the, what’s the, what did I do?”

“You know what you did, Mr. Coombs,” Carella said coldly. “You destroyed evidence of a crime.”

“That’s a felony,” Brown said, lying.

“Section 812 of the Penal Law,” Carella said.

“Look, I...”

“Come along, Mr. Coombs,” Brown said, and held out the handcuffs.

“What if I... what if I hadn’t thrown out the thing, the picture?” Coombs asked.

“Did you?”

“I didn’t. I got it. I’ll give it to you. Jesus, I’ll give it to you.”

“Get it,” Brown said.

A ferryboat is a good place for speculation. It is also a good place for listening. So on the way back to Isola, Carella and Brown each did a little speculating and a little listening.

“Four guys in the holdup,” Brown said. “Carmine Bonamico, who masterminded the job...”

“Some mastermind,” Carella said.

“Jerry Stein, who drove the getaway heap, and two guns named Lou D’Amore and Pete Ryan. Four altogether.”

“So?”

“So figure it out. Pete Ryan gave one piece of the snapshot to his aunt Dorothea McNally and another piece to his good old pal Robert Coombs...”

“Of Bob’s Famous Roadside Emporium,” Carella said.

“Correct,” Brown said, “Which means, using a method known as arithmetical deduction, that Ryan was at one time in possession of two pieces of the snapshot.”

“Correct,” Carella said.

“Is it not reasonable to assume, therefore, that each member of the gang was likewise in possession of two pieces of the snapshot?”

“It is reasonable, but not necessarily exclusive,” Carella said.

“How do you mean, Holmes?”

“Elementary. You are assuming there are only eight pieces of the full photograph. However, using other multiples of four, we can equally reason that there are twelve pieces, or sixteen pieces, or indeed...”

“My guess is eight,” Brown said.

“Why the magic number eight?”

“If you were planning a heist, would you go cutting a picture into twelve parts? Or sixteen?”

“Or twenty?” Carella said.

“Would you?”

“I think it’s a goofy idea to begin with,” Carella said. “I wouldn’t cut up a photograph at all.”

“My guess is eight. Four guys, two pieces each. We’ve now got six of them. My guess is we’ll find number seven in Gerry Ferguson’s safe. That’ll leave only one piece to go. One, baby. One more piece and we’re home free.”

As Robert Burns, that sage Scottish poet once remarked, however, the best laid plans...

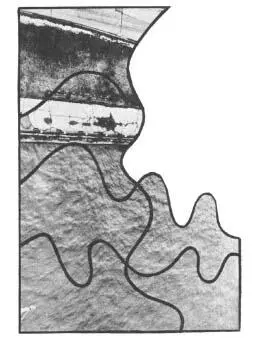

That afternoon, they went down to the Ferguson Gallery with a warrant obliging Geraldine Ferguson to open her safe. And though they searched it from top to bottom and found a lot of goodies in it, none of which were related to any crime, they did not find another piece of the photograph. By the end of that Monday, they still had only six pieces.

Six.

Count ‘em.

Six.

As they studied these assembled pieces in the midnight silence of the squadroom, something struck them as being terribly wrong. There was no sky in the picture. And because there was no sky, neither was there an up nor a down, a top nor a bottom. They were looking at a landscape without perspective, and it made no sense.

The nylon stocking was wrapped tightly around her throat, embedded in the soft flesh of her neck. Her eyes were bulging, and she lay grotesque in death upon the turquoise-colored rug in her bedroom, wearing a baby-doll nightgown and bikini panties, the bedsheets trailing off the bed and tangled in one twisted leg.

Geraldine Ferguson would never again swear in Italian, never again proposition married spades, never again charge exorbitant prices for a painting or a piece of sculpture. Geraldine Ferguson lay robbed of life in a posture as angularly absurd as the geometric designs that had shrieked from the walls of her gallery, death silent and shrill in that turquoise-matted sanctuary, the bedroom a bedlam around her, a tired reprise of the havoc wreaked in the rooms of Donald Renninger and Albert Weinberg, the searcher run amok, the quest for 750 G’s reaching a climax of desperation. The police had not found what they’d wanted in Gerry’s safe, and they wondered now if whoever had demolished Gerry’s apartment and strangled her into the bargain had had any better luck than they.

Arthur Brown went out into the hallway and, oddly, wondered if Gerry had ever roller-skated on a city sidewalk.

They picked up Bramley Kahn in a gay bar that night.

He was wearing a brocade Nehru jacket over white linen hiphuggers. His hand was resting on the shoulder of a curly-haired young man in a black leather jacket. A sculpted gold ring set with a gray freshwater pearl was on Kahn’s left pinky.

He was slightly drunk, and decidedly campy, and he seemed surprised to see the police. Everywhere around him, men danced with men, men whispered to men, men embraced men, but Kahn was nonetheless surprised to see the police because this was the most permissive city in the world, where private homosexual clubs could expressly prohibit policemen from entering (unless of course they, too, were members) and where everyone looked the other way unless a six-year-old boy was being buggered by a flying queen in a dark alley. This was just a run-of-the-mill gay bar, never any trouble here, never any strident jealous arguments, never anything more than consenting adults quietly doing their thing — Kahn was very surprised to see the police.

Читать дальше