“Hey!” Brown said. “Now we’re getting there!”

“Yeah,” Carella said, “but where?”

Never let it be bruited about that just because a homicide victim also happens to be an ex-con, the police will devote less time and energy to finding out who has done him in. Perish the thought! In this fair and democratic land of ours, the rich and the poor, the powerful and the meek, the honest citizen and the wrongdoer are all afforded equal protection under the law, even after they’re dead. So, boy oh boy, did those guys work hard trying to find out who had left the hole in Albert Weinberg’s chest!

To begin with, there are a lot of people who have to be informed when someone inconsiderately gets himself knocked off. Just informing all these different people takes a lot of time. Imagine having to call the Police Commissioner, and the Chief of Detectives, and the District Commander of the Detective Division, and Homicide, and the Squad and Precinct Commanding Officers of the precinct where the body was found, and the Medical Examiner, and the District Attorney, and the Telegraph, Telephone and Teletype Bureau at Headquarters, and the Police Laboratory, not to mention the police photographers and stenographers — the list alone is longer than the average laundry list, and just try phoning in a dirty shirt to the local laundryman. All that vast machinery of law enforcement ground into immediate action the moment it was discovered that Albert Weinberg had a hole in his chest; all those oiled gears smoothly meshed and rotated in the cause of justice; all those relentless preventers of crime and pursuers of criminals called upon their enormous reservoir of physical courage and stamina, their mental acumen, their experience, intelligence, their brilliance even — and all in an attempt to discover who had shot and killed the man who once upon a time had beat up a little old lady for the sum of seventeen dollars and thirty-four cents.

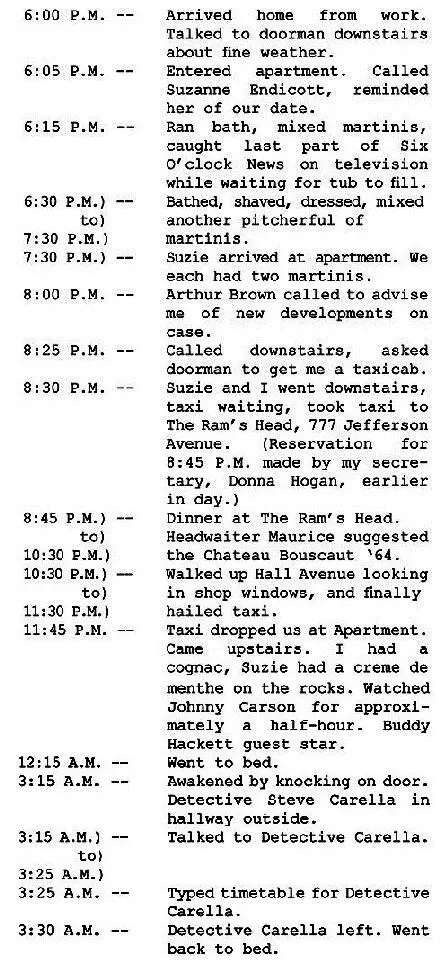

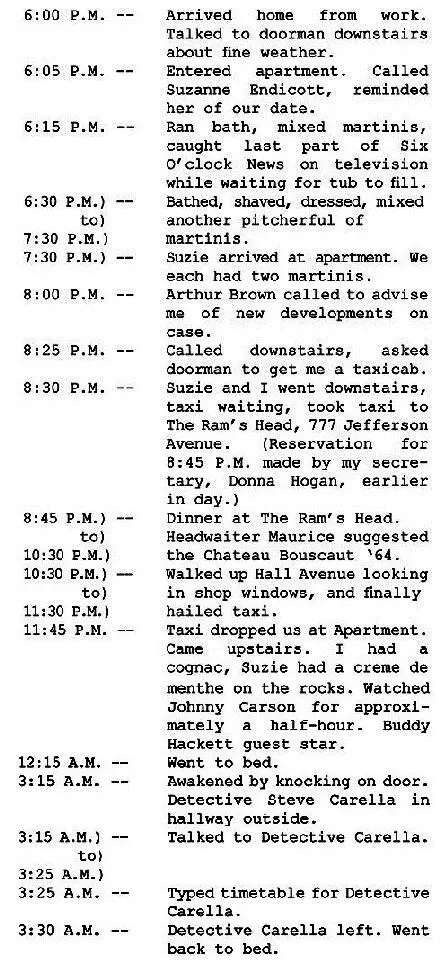

Actually, most of the physical courage and stamina, the mental acumen, the experience, intelligence and brilliance was being expended by Detectives Meyer Meyer and Cotton Hawes of the 87th Squad; Carella (who had discovered the corpse) being elsewhere occupied. Meyer and Hawes did not have much trouble taking apart the apartment; whoever killed Weinberg had already done a very good job of that. They decided after a thorough search of the place that Brown’s surmise was a correct one. The killer had been after Weinberg’s pieces of the photograph, and had apparently been successful in finding them. Meyer and Hawes questioned all of the tenants in the building and discovered that three of them had heard a very loud noise shortly after midnight. None of these people thought it either necessary or advisable to call the police. In this neighborhood, policemen were not exactly looked upon as benefactors of the people, and besides the sounds of gunfire were somewhat commonplace, day or night. So both detectives went back to the squadroom to consult the timetable Irving Krutch had so thoughtfully typed up for Steve Carella:

The day doorman outside Krutch’s apartment building corroborated that Krutch had come home from work at about 6:00 P.M., and that they had had a brief discussion about the wonderful weather, so different from last June’s weather, when the city was sweltering in the grip of a ninety-degree heat wave. He put Meyer and Hawes in touch with the night doorman who stated that Krutch had called down for a taxi at approximately 8:30, and had left the building with a young lady shortly thereafter. He had personally given Krutch’s destination to the cab driver: The Ram’s Head at 777 Jefferson Avenue. He further reported that Krutch and the young lady had come back to the apartment shortly before midnight and that he had not seen either of them leaving again at any time during his tour of duty, which ended at 8:00 A.M. Meyer and Hawes went over the building’s entrances very carefully, though, and discovered that anyone who chose not to be seen by either the doorman or the elevator operator had only to take the service steps down to the basement and leave the building through the side-street exit door, where the garbage cans were stacked.

The reservations book for The Ram’s Head noted a reservation for “Irving Krutch, 2” at 8:45 P.M. on the night Albert Weinberg was murdered. The headwaiter, a man named Maurice Duchene recalled Mr. Krutch and a young lady being there, and also recalled recommending the Chateau Bouscaut ‘64 to them. He said that Mr. Krutch had ordered a bottle and had commented that the wine was delicious. Mr. Krutch had tipped him three dollars when he left the restaurant at about 10:30.

A call to the local affiliate of the National Broadcasting Company ascertained the fact that one of Johnny Carson’s guests that night had been Buddy Hackett and that he had come on almost immediately after the monologue, sometime before midnight.

There was nothing left to do but talk to Suzanne Endicott.

Ask any cop whom he would rather interview, an eighty-year-old lady with varicose veins or a twenty-two-year-old blonde wearing a see-through blouse, just ask any cop.

Suzanne Endicott worked in a swinging boutique called The Nickel Bag, and she was wearing a leather miniskirt and a blouse through which her breasts were clearly visible. Her attire was very disconcerting, especially to policemen who were rather more used to eighty-year-old ladies with varicose veins. Detective Meyer Meyer was a married man. Cotton Hawes was a single man, but he, too, seemed to be having difficulty concentrating on the questions. He kept thinking he should ask Suzanne Endicott to go to a movie with him. Or something. The shop was thronged with young girls similarly though not identically dressed, miniskirts and tights, headbands and shiny blouses, a veritable aviary of chirping young birds — Meyer Meyer hadn’t even enjoyed the Hitchcock film. Suzanne Endicott fluttered here and there, helping this young lady with a pants suit, that one with a crocheted dress, the next with a sequined vest. Between flutterings and chirpings and quick glimpses of nipples and thighs, the detectives tried to ask their questions.

“You want to tell us exactly what happened that night?” Meyer asked.

“Oh, sure, I’d be happy to,” Suzie said. She had the faintest trace of a Southern accent in her speech, Hawes noticed.

“Where are you from originally?” he asked, thinking to put her at ease, and also thinking he would definitely ask her to go to a movie or something.

“Oh my, does my accent still show?” Suzie said.

“Just a little,” Hawes said, and tried a gentle, understanding smile that did not seem appropriate to his massive height, nor his fiery red mane, nor the white streak in the hair over his left temple, the result of a knifing many years back.

“I’m from Georgia,” she said. “The Peach State.”

“It must be lovely down there in Georgia,” Hawes said.

“Oh yes, just lovely,” Suzie said. “Excuse me, just one teeny little minute, won’t you?” she said, and dashed off to where a striking brunette was coming out of one of the dressing rooms. The brunette had on bright red velvet hip-huggers. Hawes thought he might go over and ask her to go to a movie or something.

“I feel as if I’m backstage at the Folies Bergère,” Meyer whispered.

Читать дальше