Harry said, “This way.” We veered off on a dirt hiking trail circling the foot of the mountain. Dense foliage pressed in from both sides; Harry took the lead, walking sideways on a footpath pointing straight up the slope. I followed, scrub bushes snagging my clothes and brushing my face. After fifty uphill yards, the path leveled off into a small clearing fronted by a shallow stream of running water. And there was a tiny, pillbox-style cinderblock hut, the door standing wide open.

I walked in.

The side walls were papered with pornographic photographs of crippled and disfigured women. Mongoloid faces sucking dildoes, nudie girls with withered and brace-clad legs spread wide, limbless atrocities leering at the camera. There was a mattress on the floor; it was caked with layers and layers of blood. Bugs and flies were laced throughout the crust, stuck there as they feasted themselves to death. The back wall held tacked-on color photos that looked like they were torn from anatomy texts: close-up shots of diseased organs oozing blood and pus. There were spray and spatter marks on the floor; a small spotlight attached to a tripod was stationed beside the mattress, the light fixture aimed at the center of it. I wondered about electricity, then examined the gizmo’s base and saw a battery hook-up. A blood-sprayed stack of books rested in one corner — mostly science fiction novels, with Gray’s Advanced Anatomy and Victor Hugo’s The Man Who Laughs standing out among them.

“Bucky?”

I turned around. “Go get ahold of Russ. Tell him what we’ve got. I’ll do a forensic here.”

“Russ won’t get back from Tucson till tomorrow. And kid, you don’t look too healthy to me right—”

“Goddamn it, get out of here and let me do this!”

Harry stormed out, spitting crushed pride; I thought of the proximity to Sprague property and dreamer Georgie Tilden, bum shack dweller, son of a famous Scottish anatomist. “Really? A man with a medical background?” Then I opened up my kit and raped the nightmare crib for evidence.

First I examined it top to bottom. Aside from obviously recent mud tracks — Harry’s tramps probably — I found narrow strands of rope under the mattress. I scraped what looked like abraded flesh particles off them; I filled up another test tube with blood-matted dark hair taken from the mattress. I checked the blood crust for different color shadings, saw that it was a uniform maroon and took a dozen samples. I tagged and packed the rope away, along with the anatomy pages and smut pictures. I saw a man’s bootprint, blood-outlined, on the floor, measured it and traced the sole treads onto a sheet of transparent paper.

Next it was fingerprints.

I dusted every touch, grab and press surface in the room; I dusted the few smooth spines and glossy pages in the books on the floor. The books yielded only streaks; the other surfaces brought up smudges, glove marks and two separate and distinct sets of latents. Finishing, I took a pen and circled the smaller digits on the door, doorjamb and wall molding by the mattress headboard. Then I got out my magnifying glass and Betty Short’s print blow-up and made comparisons.

One identical print;

Two;

Three — enough for a courtroom.

Four, five, six, my hands shaking because this was unimpeachably where the Black Dahlia was butchered, shaking so hard I couldn’t transfer the other set of latents to plates. I hacked a four-digit spread off the door with my knife and wrapped it in tissue — forensic amateur night. I packed up my kit, tremble-walked outside, saw the running water and knew that was where the killer drained the body. Then a strange flash of color by some rocks next to the stream caught my eye.

A baseball bat — the business end stained dark maroon.

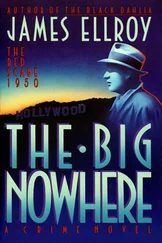

I walked to the car thinking of Betty alive, happy, in love with some guy who’d never cheat on her. Passing through the park, I looked up at Mount Lee. The sign now read just Hollywood; the band was playing, “There’s No Business Like Show Business.”

I drove downtown. The LA city personnel office and the office of the Immigration and Naturalization Service were closed for the day. I called R&I and got goose egg on Scotland-born George Tildens — and I knew I’d go crazy if I waited overnight to make the print confirmation. It came down to calling in a superior officer, breaking and entering or bribery.

Remembering a janitor cleaning up outside the personnel office, I tried number three. The old man heard my phony story out, accepted my double-sawbuck, unlocked the door and led me to a bank of filing cabinets. I opened a drawer marked CITY PROPERTY CUSTODIAL — PART-TIME, got out my magnifying glass and powder-dusted piece of wood — and held my breath.

Tilden, George Redmond, born Aberdeen, Scotland, 3/4/1896. 5 foot 11, 185 pounds, brown hair, green eyes. No address, listed as “Transient — contact for work thru E. Sprague, WE-4391.” California Driver’s license # LA 68224, vehicle: 1939 Ford pickup, license 6B119A, rubbish-hauling territory Manchester to Jefferson, La Brea to Hoover — 39th and Norton right in the middle of it. Left- and right-hand fingerprints at the bottom of the page; one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine matching comparison points — three for a conviction, six more for a one-way to the gas chamber. Hello, Elizabeth.

I closed the drawer, gave the janitor an extra ten-spot to keep him quiet, packed up the evidence kit and walked outside. I pinpointed the moment: 8:10 P.M., Wednesday, June 29, 1949, the night a flunky harness bull cracked the most famous unsolved homicide in California history. I touched the grass to see if it felt different, waved at office workers passing by, pictured myself breaking the news to the padre and Thad Green and Chief Horrall. I saw myself back at the Bureau, a lieutenant inside of a year, Mr. Ice exceeding the wildest Fire and Ice expectations. I saw my name in the headlines, Kay coming back to me. I saw the Spragues squeezed dry, disgraced by their complicity in the killing, all their money useless. And that was what kiboshed my reverie: there was no way for me to make the arrest without admitting I suppressed evidence on Madeleine and Linda Martin back in ’47. It was either anonymous glory or public disaster.

Or back-door justice.

I drove to Hancock Park. Ramona’s Cadillac and Martha’s Lincoln were gone from the circular driveway; Emmett’s Chrysler and Madeleine’s Packard remained. I parked my lackluster Chevy crossways next to them, the rear tires sunk into the gardener’s rose bush border. The front door looked impregnable, but a side window was open. I hoisted myself up and into the living room.

Balto the stuffed dog was there by the fireplace, guarding a score of packing crates lined up on the floor. I checked them out; they were filled to the top with clothes, silverware and ritzy bone china. A cardbox box at the end of the row was overflowing with cheap cocktail dresses — a weird anomaly. A sketch pad, the top sheet covered with drawings of women’s faces, was wedged into one corner. I thought of commerical artist Martha, then heard voices upstairs.

I went to them, my .45 out, the silencer screwed on tight. They were coming from the master bedroom: Emmett’s burr, Madeleine’s pout. I pressed myself to the hallway wall, eased down to the doorway and listened.

“... besides, one of my foremen said the goddamn pipes are spewing gas. There’ll be hell to pay, lassie. Health and safety code violations at the very least. It’s time for me to show the three of you Scotland, and let our Jew friend Mickey C. utilize his talent for public relations. He’ll put the onus on old Mack or the pinkos or some convenient stiff, trust me he will. And when things are kosher again, we’ll come home.”

Читать дальше