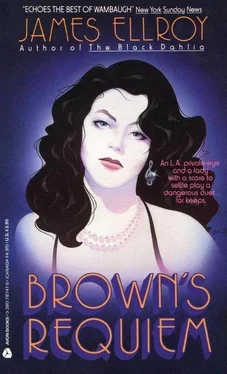

James Ellroy

Brown’s Requiem

Business was good. It was the same thing every summer. The smog and heat rolled in, blanketing the basin; people succumbed to torpor and malaise; old resolves died; old commitments went unheeded. And I profited: my desk was covered with repo orders, ranging in make and model from Datsun sedan to Eldorado rag-top, and in territory from Watts to Pacoima. Sitting at my desk, listening to the Beethoven Violin Concerto and drinking my third cup of coffee, I calculated my fees, less expenses. I sighed and blessed Cal Myers and his paranoia and greed. Our association dates back to my days with Hollywood Vice, when we were both in trouble and I did him a big favor. Now, years later, his guilty noblesse oblige supports me in something like middle-class splendor, tax free.

Our arrangement is simple, and a splendid hedge against inflation: Cal’s down payments are the lowest in L.A., and his monthly payments the highest. My fee for a repossession is the sum of the owner’s monthly whip-out. For this Cal gets the dubious satisfaction of having a licensed private investigator do his ripoffs, and implicit silence on my part regarding all his past activities. He shouldn’t worry. I would never rat on him for anything, under any circumstances. Still, he does. We never talk about these things; our relationship is largely elliptical. When I was on the sauce, he felt he had the upper hand, but now that I’m sober he accords me more intelligence and cunningness than I possess.

I surveyed the figures on my scratch pad: 11 cars, a total of $1,881.00 in monthlies, less 20 percent or $376.20 for my driver. $1,504.80 for me. Things looked good. I took the record off the turntable, dusted it carefully, and replaced it in its sleeve. I looked at the Joseph Karl Stieler print on my living room wall: Beethoven, the greatest musician of all time, scowling, pen in hand, composing the Missa Solemnis, his face alight with inword heroism.

I called Irwin, my driver, and told him to meet me at my place in an hour and to bring coffee — there was work on the line. He was grumpy until I mentioned money. I hung up and looked out my window. It was getting light. Hollywood, below me, was filling up with hazy sunshine. I felt a slight tremor: part caffeine, part Beethoven, part a last passage of night air. I felt my life was going to change.

It took Irwin forty minutes to make the run from Kosher Canyon. Irwin is Jewish, I’m a second generation German-American, and we get along splendidly; we agree on all important matters: Christianity is vulgar, capitalism is here to stay, rock and roll is evil, and Germany and judaica, as antithetical as they may be, have produced history’s greatest musicians. He beeped the horn, and I clipped on my holster and went outside.

Irwin handed me a large cup of Winchell’s black and a bag of donuts as I got in the car beside him. I thanked him, and dug in. “Business first,” I said. “We’ve got eleven delinquents. Mostly in South Central L.A. and the East Valley. I’ve got credit reports on all of them and the people all have jobs. I think we can hit one a day, early mornings at the home addresses. That will get you to work on time. What we don’t snatch there, I’ll work on myself. Your cut comes to three hundred seventy-six dollars and twenty cents, payable next time I see Cal. Today we visit Leotis McCarver at 6318 South Mariposa.”

As Irwin swung his old Buick onto the Hollywood Freeway southbound, I caught him looking at me out of the corner of his eye and I knew he was going to say something serious. I was right. “Have you been all right, Fritz?” he asked. “Can you sleep? Are you eating properly?”

I answered, somewhat curtly, “I feel better in general, the sleep comes and goes, and I eat like a horse or not at all.”

“How long’s it been, now? Eight, nine months?”

“It’s been exactly nine months and six days, and I feel terrific. Now let’s change the subject.” I hated to cut Irwin off, but I feel more comfortable with people who talk obliquely.

We got off the freeway around Vermont and Manchester and headed west to the Mariposa address. I checked the repo order: a 1978 Chrysler Cordoba, loaded. $185 a month. License number CTL 412. Irwin turned north on Mariposa, and in a few minutes we were at the 6300 block, I fished out my master keys and detached the ’78 Chrysler’s. 6318 was a two-story pink stucco multi-unit dump, ultra-modern twenty years ago, with side entrances, and an ugly schematic flamingo in black metal on the wall facing the street. The garage was subterranean, running back the whole length of the building.

Irwin parked in front. I handed him the original of the repo order and tucked the carbon into my back pocket. “You know the drill, Irwin. Stand by your car, whistle once if anyone enters the garage, twice if the fuzz show up. Be prepared to explain what I’m doing. Hold on to the repo order.” Irwin knows the procedure as well as I do, but even after five years of legalized ripoffs, the whole deal still makes me nervous, and I repeat the instructions for luck. Strange things can happen, have happened, and the L.A.P.D. is notoriously trigger-happy. Having been one of them, I know.

I dropped down into the garage. I expected it to be dark, but the morning sunshine reflecting off the windows of the adjacent apartments provided plenty of light. When I spotted CTL 412, the third car from the end, I started to laugh. Cal Myers was going to shit. Leotis McCarver was undoubtedly black, but his car was a full dress taco wagon: chopped, channeled, lowered, with a candy apple, lime-green paint job with orange and yellow flames covering the hood and sweeping halfway back over the sides of the vehicle. Black enamel script over the rear wheel wells announced that this was the “Dragon Wagon.” I got out my master key and opened it. The interior was just as esoteric: fuzzy black and white zebra-striped upholstery, pink velveteen dice hanging from the rear-view mirror, and a furry orange accelerator pedal in the shape of a naked foot. The customizing must have cost old Leotis a fortune.

I was still laughing when I heard the scrape of a footstep off to my left near the back end of the garage. I turned and saw a black man almost as big as I am striding toward me. There was no time to avoid a confrontation. When he was ten feet away, he screamed “Motherfucker” and charged me. I was in the walkway now, and just before he made contact I sidestepped and tripped him with a kick at his knee. As he struggled to get to his feet I kicked him once in the face, once in the neck, and once in the groin. He was moaning and spitting out teeth.

I dragged him over between two cars near the back of the garage and patted him down for weapons. Nothing. I left him there, got into his chariot, and pulled out onto Mariposa. Irwin was still standing there by his car, as if nothing had happened. “He tried to jump me, and I waxed him. Get out of here. Tomorrow, same time, my place.” Irwin turned pale. This was the first time anything like this had happened. “Didn’t you hear anything?” I yelled. I jammed on the gas, peeling rubber.

I looked in the fur-bordered rear-view mirror. Irwin was just starting to get into his car. He looked like he was trembling. I hoped he wouldn’t quit me.

I turned left on Slauson and right on Western, half a mile later. I had been driving for five minutes or so when I discovered that I was trembling. It got worse, so bad that I could hardly hold the wheel steady. Then I felt my stomach start to churn and turn over. I pulled into the parking lot of a liquor store, got out, and vomited on the pavement until my stomach and lungs ached. My vomit tasted like coffee and sugar and fear. After a few minutes I started to calm down. A group of gangly black youths lounging against the liquor store wall and passing around a bottle of cheap wine had watched the whole scene, laughing at me like I was some rare breed of alien from outer space. I took several deep breaths, got back into the car and headed out to the Valley to see Cal Myers.

Читать дальше