Nobody paid Rebus and Jack any heed as they walked towards the camp-fire. Rebus kept his hands in his pockets, and tried not to make fists of them.

‘Looking for Jo,’ he said. He recognised the guitar chords: ‘Time of the Preacher’. He tried again. ‘Joanna Bruce.’

‘Bummer,’ someone said.

‘That could be arranged,’ Jack cautioned.

The joint went from hand to hand. ‘Decade from now,’ someone else said, ‘this won’t be illegal. It might even be on prescription.’

Smoke billowed from grinning mouths.

‘Joanna,’ Rebus reminded them.

‘Warrant?’ the guitarist asked.

‘You know better than that,’ Rebus told her. ‘I only need a warrant if I want to bust this place. Want me to fetch one?’

‘Macho Man!’ someone sang.

‘What do you want?’

There was a small white caravan hooked up to an antiquated Land Rover. She’d opened the caravan door — just the top half — and was leaning out.

‘Can you smell the bacon, Jo?’ the guitarist asked.

‘Need to talk to you, Joanna,’ Rebus said, walking towards the caravan, ‘about Mitch.’

‘What about him?’

‘Why he died.’

Joanna Bruce looked at her fellow travellers, saw that Rebus had their attention, and unlocked the bottom half of her door. ‘Better come in,’ she said.

The caravan was cramped and unheated. There was no TV, but untidy stacks of magazines and newspapers, some of them with articles clipped out, and on the small folding table — benches either side, the whole thing convertible into a bed — a laptop computer. Standing, Rebus’s head touched the caravan roof. Joanna shut down the computer, then gestured for Rebus and Jack to take the bench seats, while she balanced atop a pile of magazines.

‘So,’ she said, folding her arms, ‘what’s the story?’

‘My question exactly,’ Rebus replied. He nodded towards the wall behind her, where some photos had been pinned for decoration. ‘Snap.’ She looked round at the pictures. ‘I’ve just had another lot of those developed,’ Rebus explained: they were the originals missing from Mitch’s envelope. She sat there with a face like stone, giving nothing away. There was kohl around her eyes and her hair was white fire in the glow from the gas lighting. For a full half-minute, the soft roar of igniting gas was the only sound in the caravan. Rebus was giving her time to change her mind, but she was using that time to erect further barricades, her eyes closing to slits, mouth pressed shut.

‘Joanna Bruce,’ Rebus mused. ‘Interesting choice of name.’ She half-opened her mouth, closed it again.

‘Is Joanna your real first name, or did you change that too?’

‘What do you mean?’

Rebus looked at Jack, who was sitting back, trying to look the part of the relaxed visitor, telling her it wasn’t two against one, that she’d no need to be afraid. When Rebus spoke, he spoke to Jack’s face.

‘Your real surname’s Weir.’

‘How... who told you that?’ Trying to laugh it off.

‘Nobody needed to. Major Weir had a daughter; they fell out; he disowned her.’ And changed her sex to a son, maybe to muddy the water. Mairie’s source had said as much.

‘He didn’t disown her! She disowned him !’

Rebus turned to her. Her face and body were animated now, clay come to life. Her fists gouged at her knees.

‘Two things put me on track,’ he said quietly. ‘One, that surname: Bruce, as in Robert the... as any student of Scottish history would know. Major Weir is daft on Scots history, he even named his oilfield after Bannockburn, which as we know was won by Robert the Bruce. Bruce and Bannock. I’m guessing you picked the name because you thought it would rile him?’

‘It riles him all right.’ Half a smile.

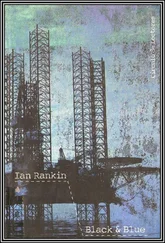

‘The second thing was Mitch himself, once I knew you two were friends. Jake Harley tells me Mitch had gleaned some gen on Negrita , top-secret stuff. Well, Mitch might have been resourceful in some areas, but I couldn’t see how he’d manage to work his way back through a paper trail. He travelled light, no sign of any notes or anything like that, either in his flat or in his cabin. I’m assuming he got the gen from you?’ She nodded. ‘And you’d have to seriously have it in for T-Bird Oil to bother with that sort of labyrinth in the first place. But we already know you’ve got something against T-Bird — the demo outside their HQ; chaining yourself to Bannock in full view of the TV cameras. I thought maybe it was something personal...’

‘It is.’

‘Major Weir’s your father?’

Her face turned sour and strangely childlike. ‘Only in the biological sense. Even then, if you could get a gene transplant I’d be at the front of the queue.’ Her voice sounded more American than ever. ‘Did he kill Mitch?’

‘Do you think he did?’

‘I’d like to think so.’ She stared at Rebus. ‘I mean, I’d like to think he’d sink that low.’

‘But?’

‘But nothing. Maybe he did, maybe he didn’t.’

‘You reckon he had the motive?’

‘Sure.’ Not aware she was doing it, she picked at a nail and then bit it, before starting on another. ‘I mean, Negrita and the way T-Bird’s culpability was hushed up... and now the dumping. He had plenty of economic reasons.’

‘Was Mitch threatening to go to the media with the story?’

She removed a sliver of nail from her tongue. ‘No, I think he was trying blackmail first. Keep quiet about everything, so long as T-Bird went for ecological scrapping of Bannock.’

‘Everything?’

‘What?’

‘You said “everything”, like there was more.’

She shook her head. ‘No.’ But she wasn’t looking at him.

‘Joanna, let me ask you something: why didn’t you go to the media, or try blackmail on your father? Why did it have to be Mitch?’

She shrugged. ‘He had the chutzpah .’

‘Did he?’

Another shrug. ‘What else?’

‘See, the way it looks to me... you don’t mind tormenting your father — as publicly as possible. You’re at the front of every demo, you make sure your picture’s on TV... but if you actually came forward and let the world know who you are , that would be even more effective. Why the secrecy?’

Her face turned childlike again, her mouth busy with fingers, knees together. The single braid fell between her eyes, like she wanted to hide from the world but be caught at the same time — a child’s game.

‘Why the secrecy?’ Rebus repeated. ‘Seems to me it’s precisely because this is so personal between you and your father, like some sort of private game. You like the idea of torturing him, letting him wonder when you’ll go public with any of this.’ He paused. ‘Seems to me maybe you were using Mitch.’

‘No!’

‘Using him to get at your father.’

‘No!’

‘Which means he had something you found useful. What could that be?’

She got up. ‘Get out!’

‘Something that drew the two of you together.’

She clamped her hands over her ears, shaking her head.

‘Something from your past... your childhoods. Something like blood between you. How far back does it go, Jo? Between you and your father — how far into the past does it stretch?’

She swung around and slapped his face. Hard. Rebus rode it, but it still stung.

‘So much for non-violent protest,’ he said, rubbing the spot.

She slumped down on the magazines again, ran a hand over her head. It came to rest on one of her braids, which she twirled nervously. ‘You’re right,’ she said, so quietly Rebus almost didn’t hear.

‘Mitch?’

‘Mitch,’ she said, remembering him at last. Allowing herself that pain. Behind her, lighting flickered over the photographs. ‘He was so uptight when we met. Nobody could believe it when we started seeing one another — chalk and cheese they said. They were wrong. It took a while, but one night he opened up to me.’ She looked up. ‘You know his background?’

Читать дальше