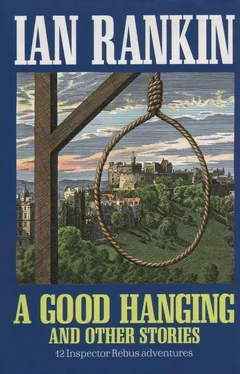

Ian Rankin

A Good Hanging and other stories

It was the perfect murder.

Perfect, that is, so far as the Lothian and Borders Police were concerned. The murderer had telephoned in to confess, had then panicked and attempted to flee, only to be caught leaving the scene of the crime. End of story.

Except that now he was pleading innocence. Pleading, yelling and screaming it. And this worried Detective Inspector John Rebus, worried him all the way from his office to the four-storey tenement in Leith’s trendy dockside area. The tenements here were much as they were in any working-class area of Edinburgh, except that they boasted colour-splashed roller blinds or Chinese-style bamboo affairs at their windows, and their grimy stone facades had been power-cleaned, their doors now boasting intruder-proof intercoms. A far cry from the greasy Venetian blinds and kicked-in passageways of the tenements in Easter Road or Gorgie, or even in nearby parts of Leith itself, the parts the developers were ignoring as yet.

The victim had worked as a legal secretary, this much Rebus knew. She had been twenty-four years old. Her name was Moira Bitter. Rebus smiled at that. It was a guilty smile, but at this hour of the morning any smile he could raise was something of a miracle.

He parked in front of the tenement, guided by a uniformed officer who had recognised the badly dented front bumper of Rebus’s car. It was rumoured that the dent had come from knocking down too many old ladies, and who was Rebus to deny it? It was the stuff of legend and it gave him prominence in the fearful eyes of the younger recruits.

A curtain twitched in one of the ground-floor windows and Rebus caught a glimpse of an elderly lady. Every tenement, it seemed, tarted up or not, boasted its elderly lady. Living alone, with one dog or four cats for company, she was her building’s eyes and ears. As Rebus entered the hallway, a door opened and the old lady stuck out her head.

‘He was going to run for it,’ she whispered. ‘But the bobby caught him. I saw it. Is the young lass dead? Is that it?’ Her lips were pursed in keen horror. Rebus smiled at her but said nothing. She would know soon enough. Already she seemed to know as much as he did himself. That was the trouble with living in a city the size of a town, a town with a village mentality.

He climbed the four flights of stairs slowly, listening all the while to the report of the constable who was leading him inexorably towards the corpse of Moira Bitter. They spoke in an undertone: stairwell walls had ears.

‘The call came at about 5 a.m., sir,’ explained PC MacManus. ‘The caller gave his name as John MacFarlane and said he’d just murdered his girlfriend. He sounded distressed by all accounts, and I was radioed to investigate. As I arrived, a man was running down the stairs. He seemed in a state of shock.’

‘Shock?’

‘Sort of disorientated, sir.’

‘Did he say anything?’ asked Rebus.

‘Yes, sir, he told me, “Thank God you’re here. Moira’s dead.” I then asked him to accompany me upstairs to the flat in question, called in for assistance, and the gentleman was arrested.’

Rebus nodded. MacManus was a model of efficiency, not a word out of place, the tone just right. Everything by rote and without the interference of too much thought. He would go far as a uniformed officer, but Rebus doubted the young man would ever make CID. When they reached the fourth floor, Rebus paused for breath then walked into the flat.

The hall’s pastel colour scheme extended to the living-room and bedroom. Mute colours, subtle and warming. There was nothing subtle about the blood though. The blood was copious. Moira Bitter lay sprawled across her bed, her chest a riot of colour. She was wearing apple-green pyjamas, and her hair was silky blonde. The police pathologist was examining her head.

‘She’s been dead about three hours,’ he informed Rebus. ‘Stabbed three or four times with a small sharp instrument, which, for the sake of convenience, I’m going to term a knife. I’ll examine her properly later on.’

Rebus nodded and turned to MacManus, whose face had a sickly grey tinge to it.

‘Your first time?’ Rebus asked. The constable nodded slowly. ‘Never mind,’ Rebus continued. ‘You never get used to it anyway. Come on.’

He led the constable out of the room and back into the small hallway. ‘This man we’ve arrested, what did you say his name was?’

‘John MacFarlane, sir,’ said the constable, taking deep breaths. ‘He’s the deceased’s boyfriend apparently.’

‘You said he seemed in a state of shock. Was there anything else you noticed?’

The constable frowned, thinking. ‘Such as, sir?’ he said at last.

‘Blood,’ said Rebus coolly. ‘You can’t stab someone in the heat of the moment without getting blood on you.’

MacManus said nothing. Definitely not CID material and perhaps realising it for the very first time. Rebus turned from him and entered the living-room. It was almost neurotically tidy. Magazines and newspapers in their rack beside the sofa. A chrome and glass coffee table bearing nothing more than a clean ashtray and a paperback romance. It could have come straight from an Ideal Home exhibition. No family photographs, no clutter. This was the lair of an individualist. No ties with the past, a present ransacked wholesale from Habitat and Next. There was no evidence of a struggle. No evidence of an encounter of any kind: no glasses or coffee cups. The killer had not loitered, or else had been very tidy about his business.

Rebus went into the kitchen. It, too, was tidy. Cups and plates stacked for drying beside the empty sink. On the draining-board were knives, forks, teaspoons. No murder weapon. There were spots of water in the sink and on the draining-board itself, yet the cutlery and crockery were dry. Rebus found a dishtowel hanging up behind the door and felt it. It was damp. He examined it more closely. There was a small smudge on it. Perhaps gravy or chocolate. Or blood. Someone had dried something recently, but what?

He went to the cutlery drawer and opened it. Inside, amidst the various implements was a short-bladed chopping knife with a heavy black handle. A quality knife, sharp and gleaming. The other items in the drawer were bone dry, but this chopping knife’s wooden handle was damp to the touch. Rebus was in no doubt: he had found his murder weapon.

Clever of MacFarlane though to have cleaned and put away the knife. A cool and calm action. Moira Bitter had been dead three hours. The call to the police station had come an hour ago. What had MacFarlane done during the intervening two hours? Cleaned the flat? Washed and dried the dishes? Rebus looked in the kitchen’s swing-bin, but found no other clues, no broken ornaments, nothing that might hint at a struggle. And if there had been no struggle, if the murderer had gained access to the tenement and to Moira Bitter’s flat without forcing an entry... if all this were true, Moira had known her killer.

Rebus toured the rest of the flat, but found no other clues. Beside the telephone in the hall stood an answering machine. He played the tape, and heard Moira Bitter’s voice.

‘Hello, this is Moira. I’m out, I’m in the bath, or I’m otherwise engaged.’ (A giggle.) ‘Leave a message and I’ll get back to you, unless you sound boring.’

There was only one message. Rebus listened to it, then wound back the tape and listened again.

‘Hello, Moira, it’s John. I got your message. I’m coming over. Hope you’re not “otherwise engaged”. Love you.’

John MacFarlane: Rebus didn’t doubt the identity of the caller. Moira sounded fresh and fancy-free in her message. But did MacFarlane’s response hint at jealousy? Perhaps she had been otherwise engaged when he’d arrived. He lost his temper, blind rage, a knife lying handy. Rebus had seen it before. Most victims knew their attackers. If that were not the case, the police wouldn’t solve so many crimes. It was a blunt fact. You double bolted your door against the psychopath with the chainsaw, only to be stabbed in the back by your lover, husband, son or neighbour.

Читать дальше