‘I don’t blame you for going into hiding,’ Rebus said. ‘Probably the safest thing you could have done.’

‘Poor Mitch.’ Harley looked down at the ground. He was tall, well built, with short, thinning black hair and metal-rimmed glasses. His face had retained a touch of the schoolboy, but he was badly needing a shave and to wash his hair. The tent’s flaps were open, showing ground-mat, sleeping bag, a radio and some books. Leaning against the interior wall of the broch was a red rucksack, and nearby a camping-stove and carrier bag filled with rubbish.

‘Can we talk about it?’ Rebus asked.

Jake Harley nodded. He saw that Jack Morton was more interested in the broch itself than in their conversation. ‘Isn’t it incredible?’

‘Bloody right,’ Jack said. ‘Did it ever have a roof?’

Harley shrugged. ‘They built lean-tos in here, so maybe they didn’t need a roof up there. The walls are hollow, double-thick. One of the galleries still leads to the top.’ He looked around. ‘There’s a lot we don’t know.’ Then he looked at Rebus. ‘It’s been here two thousand years. It’ll be here long after the oil’s gone.’

‘I don’t doubt that.’

‘Some people can’t see it. Money’s made them short-sighted.’

‘You think this is all about money, Jake?’

‘Not all of it, no. Come on, I’ll show you the Haa.’

So they walked back out into the wind, crossing the grazing land and coming to the low wall around what had been a good-sized stone-built house, only the shell of which remained. They circuited the boundary, Briony walking with them, Jack further back, reluctant to leave the broch.

‘Mousa Broch has always been lucky for the hunted. There’s a story in the Orkneyinga Saga , an eloping couple took shelter here...’ He smiled at Briony.

‘You found out Mitch was dead?’ Rebus asked.

‘Yes.’

‘How?’

‘I phoned Jo.’

‘Jo?’

‘Joanna Bruce. Mitch and her had been seeing one another.’ So at last Braid-Hair had a name.

‘How did she know?’

‘It was in the Edinburgh paper. Jo’s a media checker — she reads all the papers first thing every morning to see if there’s anything the various pressure groups should know.’

‘You didn’t tell Briony?’

Jake took his girlfriend’s hand and kissed it. ‘You’d only have worried,’ he told her.

‘Two questions, Mr Harley: why do you think Mitch was killed, and who was responsible?’

Harley shrugged. ‘As to who did it... I’d never be able to prove anything. But I know why he was killed — it was my fault.’

‘Your fault?’

‘I told him what I suspected about the Negrita .’

The ship Sheepskin had mentioned on the flight to Sullom Voe; afterwards clamming up.

‘What happened?’

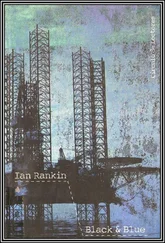

‘It was a few months back. You know Sullom Voe has some of the strictest procedures going? I mean, time was tankers would swill out their dirty bilges as they approached the coast — it saved pumping them ashore at the terminal... saved time, which meant money . We used to lose black guillemots, great northern divers, shags, eider ducks, even the otters. That doesn’t happen now — they tightened up. But mistakes still happen. That’s all the Negrita was, a mistake.’

‘An oil spill?’

Harley nodded. ‘Not a big one, not by the standards we’ve managed to set with Braer and Sea Empress . The first mate, who should have been in charge, was in the sick bay — bad hangover apparently. A crew member who hadn’t done the job before hit the wrong sequence of levers. The thing was, the crew member didn’t have any English. That’s not unusual these days: the officers might be British, but the hired help is the cheapest the company can get, which usually means Portuguese, Filipino, a hundred other nationalities. My guess is, the poor sod just didn’t understand the instructions.’

‘It was hushed up?’

Harley shrugged. ‘Never really news in the first place, not a big enough spill.’

Rebus frowned. ‘So what’s the problem?’

‘Like I say, I told Mitch the story...’

‘How did you know?’

‘The crew landed at the terminal. They were in the canteen. I got talking to one of them, he looked awful — I can speak a bit of Spanish. He told me he did it.’

Rebus nodded. ‘And Mitch?’

‘Well, Mitch found out something that had been covered up. Namely the tanker’s real owners. It’s not easy with these boats — they’re registered here, there and everywhere, leaving a real paper trail in their wake. Not always easy to get details from some of the registration ports. And sometimes the name on the papers doesn’t mean much — companies own other companies, more countries are involved...’

‘A real maze.’

‘Purposely so: a lot of the tankers out there are in shocking condition. But maritime law is international — even if we wanted to stop them landing, we couldn’t, not without the say-so of all the other signatories.’

‘Mitch found out that T-Bird Oil owned the tanker?’

‘How did you know?’

‘An educated guess.’

‘Well, that’s what he told me.’

‘And you think someone at T-Bird had him killed? But why? Like you say, it wasn’t a newsworthy spill.’

‘It would be with T-Bird in the frame. They’re going all out to persuade the government to let them dump their platforms at sea. They’re talking up the environment and their record in that area. We’re Mr Clean, so let us do what we want.’ Harley showed bright white teeth as he spoke, the words almost a sneer. ‘So tell me, Inspector, am I being paranoid? Just because Mitch gets thrown out of a window doesn’t mean he was assassinated, right?’

‘Oh, he was assassinated all right. But I’m not sure the Negrita had much to do with it.’ Harley stopped walking and looked at him. ‘I think you’d be quite safe going back home, Jake,’ Rebus said. ‘In fact, I’m sure of it. But first, there’s something I need.’

‘What?’

‘An address for Joanna Bruce.’

The trip back was a real follicle transplant — hairier even than the trip out. They’d taken Jake and Briony back to Brae, then dropped the car off at Lerwick and begged a lift to Sumburgh. Forres was still in the huff, but relented eventually and checked the flights back, one of which gave them enough time for a Cup-a-Soup at the station.

At Dyce, they climbed back into Jack’s car and sat there for a couple of minutes, adjusting to being back on the ground. Then they headed south on the A92, using the directions Jake Harley had given them. It was the same road Rebus had been taken on the night Tony El had been killed. They had Stanley for that — no matter what. Rebus wondered what else the young psychopath might spill, especially now he’d lost Eve. He’d know she’d flown; he’d know she wouldn’t have left the loot behind. Maybe Gill would have twisted more stories out of him.

It could be the making of her.

They saw signposts to Cove Bay, followed Harley’s instructions and came to a lay-by, behind which were parked a dozen vans, caravans, buses and campers. Bumping over ineffectual earth mounds, they came into a clearing in front of a forest. Dogs were barking, kids out playing with a punctured football. Clothes-lines hung between branches, and someone had lit a bonfire. A few adults had parked themselves around the fire, passing joints, one woman strumming a guitar. Rebus had been to travellers’ camps before. They came in two designs. There was the old-style gypsy camp, with smart caravans and builders’ lorries, the inhabitants — Romanies — olive-skinned and lapsing into a tongue Rebus couldn’t understand. Then there were the ‘New Age travellers’: usually with buses which had passed their last MOT on a wing and a prayer. They were young and savvy, cut dead wood for fuel, and worked the social security system, despite government attempts to render it unworkable. They gave their kids names the kids would kill them for when they grew up.

Читать дальше