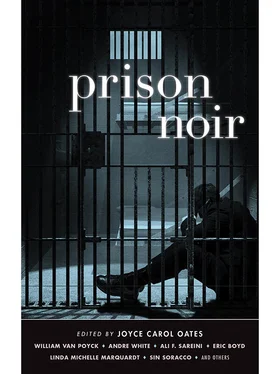

Джойс Оутс - Prison Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Джойс Оутс - Prison Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: akashic books, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Prison Noir

- Автор:

- Издательство:akashic books

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Prison Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Prison Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Prison Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Prison Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

When I return to my pod, cell 25 has been entirely disinfected of Jennings’s death. It is conspicuously off balance. The bottom bunk is devoid of sheets. A silver, rubbery pillow sits on top of the thin exercise pad of a mattress. Half the shelf space on the wall is empty and the ledge for a TV set is vacant. An empty foot locker’s lid is propped open against the wall and Rourke’s fan is on the ground, slightly angled downward, rattling at high speed to evaporate the residual moisture of a recently mopped floor. In the evaporating reflections I am haunted by a memory of my father.

Attention in the facility:

count time, count time, twenty-one thirty.

I was thinking of my father’s money when I signed his DNR order. I often wonder if that qualifies as being the first crime I committed. Not technically, of course, but a crime of conscience no less, and I’ve been plagued with guilt ever since. The Bardo Todrol Chenmo says that the quality of thoughts of those surrounding the dying has a dramatic effect on the transitioning process. I hated my job, despised my marriage, and was burned out from my father going in and out of the hospital those three preceding weeks. I was in debt too. Credit cards. Loans. Thirty thousand dollars worth of emotional compensation and a newborn son. First Fidelity National Bank. That’s what I was thinking when I crossed that last T on my signature that authorized my father’s passing.

One at a time the guards peek into my cell door window counting my body. It’s not always the same two, so the countenances I see reflect myriad emotions. Contentment. Pride. Stoicism. Self-righteousness. Judgment. I know they access our files on the department computer, reading the synopses of our crimes for entertainment. Some offer this information to certain inmates. It makes for an interesting dynamic — a hierarchy of criminal severity thriving on the economics of trickle-down loathing.

My cellie tells me that he feels like crying. He’s been down for twenty-one years and doesn’t see parole for another five. He doesn’t miss Jennings. He feels like crying because he is Jennings. Fifty-six years old. Same age as my father when he died. It’s the proximity between Jennings’s release date and the day he died that’s getting to my cellie. Dying in prison is one thing. Dying in prison less than a month shy of your parole date is entirely different. We tell each other stories of similar tragedies. A man I knew at Sterling had a heart attack while on the can. He even looked like the Mexican version of Elvis. Rodriguez was his name. Back in prison for a six-month turnaround for parole violation. A technicality. He’d served five months of it before he died. And there was the kid who got killed six hours after he stepped off the prison bus — ran across Speer Street and died on impact. My cellie told me about a convict who’d been stabbed to death in Limon three days before he was supposed to kill his number. Another man who, on the eve of his release date, strangled his best friend over a game of pinochle.

I think about my own mandatory release date, what brought me to prison, and whether there’s any credibility to the theory that sometimes remorse and guilt come first, then the act which justifies it.

Attention in the facility:

the facility has been accepted by graveyard shift, twenty-two hundred.

The overhead lights go out. The light from my cellie’s television remains, flickering wonder on the cinder block walls I stare at. The lotus posture is uncomfortable for me, so I simply cross my legs casually. I imagine the light, with its spastic flashes and barely audible cathode tube pops to be the dharmakaya — the brilliance one sees when the body is ready to release its consciousness. They say there is a review of every thought, word, and action. Not like a movie, but rather an infinite table upon which the delicate knickknack moments of your life are arranged in all directions. You can see how they affect one another, and how they affect the lives of others. At any time while in this state, you can instantly examine any one of these tchotchkes of consciousness and be held accountable for every fingerprint, crack, and degradation you inflicted upon them. I imagine this is only a joyous prospect for a select few. Supposedly, while you’re experiencing the pain and discomfort you’ve caused others, there’s something of a divine presence, a feeling about you and within you that asks — not vocally but empathetically— Have you learned to love yet? And I go to sleep afraid and without an answer.

Attention in the facility:

the facility has been accepted by day shift, zero six hundred.

When I dream of my father, he is sick. And unlike before he died, I am aware of how little time he has left. We are in a car, one of his I’d seen in an old photograph. I am driving and my father is sitting in the backseat, convalescing. I feel the shame for having spent all his money. I sense he already knows, and that he desperately wants to talk to me. Also, he senses that I want to talk to him. But we don’t speak. We just glance at each other forlornly when the other isn’t looking as I drive around a foreign city searching for a bank that does not exist. I usually wake up crying.

What is it that I really miss? What is it that I’ve truly lost if not my fleeting perceptions? Perceptions of others. Of myself. Of who I’m supposed to be, and what I once was. For my entire life I considered Dad to be the quintessential lady’s man. Tall, dark, handsome. The cool, quiet type. And gentle as a lamb. He was a mechanic and a millwright and in the 1960s he even modeled for some technical publications showcasing the latest machinery his company built. Nothing like GQ , of course, but even when he was captured in the drab beige coveralls, standing next to some drill press, it was easy to see why his nickname was Butch.

That is why, after he died, it was such a shock to discover those digital photos. I was rifling through his computer looking for information to consolidate his estate. Never in a million years could I have guessed.

There, wearing nothing but blue garters and panty hose, was the same man who taught me how to use calipers and change the brakes on my car. It was the same man who whistled at women on the beach, went to strip clubs, and was accused by both ex-wives of being the biggest womanizer on earth. And I remember being angry and ashamed. Angry because I felt robbed of my father a second time, because his secret must have been who he really was. Ashamed because I instantly recalled a moment — one of many — of my thoughtless use of the words fag, homo, and pansy over the years that probably helped to keep him a secret from me. I didn’t need to experience the dharmakaya to show me this. I deleted the photos as viciously as Jennings’s name tag was stripped from his cell door.

Attention in the facility:

count is clear, count is clear, zero six twenty.

In Tibet, they do not bury nor cremate their dead. It isn’t something to hide. It isn’t something you can cover even if you had at your disposal all the mass of the Himalayas. They have charnel grounds — hallowed stretches of mountainside where corpse, clothing, and prayer flag rot gradually over time. It is quite public and not isolated from where Tibetans live and work and play. There is even a person whose duty it is to break the body apart in a precise manner, celebrating and inviting the process in honor of the dead.

Perhaps that’s why we are given time in these manageable Pavlovian chunks. An hour here, two there. Because it’s easier to choke down, unchewed, in a ravenous frenzy that leaves us salivating with anticipation for the next cold scraps of the clock’s gristle and bone. Ten, twenty, even thirty years can be swallowed over the course of a few thousand bardos.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Prison Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Prison Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Prison Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.