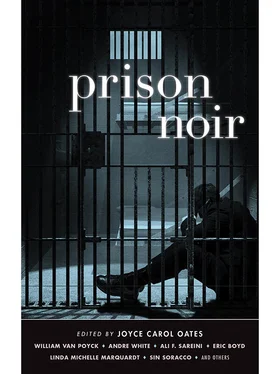

Джойс Оутс - Prison Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Джойс Оутс - Prison Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: akashic books, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Prison Noir

- Автор:

- Издательство:akashic books

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Prison Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Prison Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Prison Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Prison Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I look across the day hall as I wait to be counted, and I see cell 25, Jennings’s cell. His name tag is still on the door. I can’t read it from this distance, but the stainless steel plate remains hidden by the white of the tag. Through the small window I spot Jennings’s cellie, Rourke, who resembles Martin Mull. I expect Jennings to pop his head into view at any moment. The anticipation is so intense, I can see him clearly. Effeminate. Quiet. Fine white hair cut close and neat, conforming to the natural, Franciscanesque male-pattern baldness. Thick black plastic frames of those state-issue eyeglasses — the ones most inmates call Chomo-nator 5000s. Signature spectacles with subsequent magnification stereotypically attributed to chomos — child molesters. Perfectly round belly. A rubbery pouch of skin for a neck. Legs as thin as Pixy Stix. That was Jennings.

The guards converge, discussing their numbers. I can’t hear them, but their inflections speak of confusion. One of them has obviously accused the other of a surplus, or a deficiency. They walk back to cell 25. One guard points to Jennings’s name tag while the other nods in agreement. They talk in monotonous tones, as though discussing physics equations or dismissing the superstition that counting a dead man will bring you a year of bad luck for every year of the deceased’s sentence. I make out only bits and pieces, but I distinctly hear one of them say, “Died this morning.” A guard strips Jennings’s name tag from the door like a bandage yanked from hair and skin. The zip of the peeling packing tape shocks me violently.

Attention in the facility:

count is clear, count is clear, seventeen fifteen.

I’d seen Jennings at lunchtime, hunched at the toilet stall, ashen, making careful and deliberate movements. I offered nothing. Said nothing, except, “You look pale,” to which he replied, “I’ve been feeling like shit all week.” It was the only time I’d ever spoken to him. He shuffled out of the pod, into the sergeant’s office, and begged to be taken to medical. At first they made him walk, but when he collapsed on the steps leading into the main corridor, they rushed him to the clinic in a wheelchair.

That’s what hit me the hardest after the lieutenant announced Jennings had passed away — that I’d hardly thought about what I witnessed earlier in the day. From the entire time between those two moments were thousands of thoughts, and not one of them was of Jennings. I defended myself. I never knew the man. I may have seen him five or six times a day, every day for the last year — even sat with him at the chow hall — yet I never knew the man, never even spoke to him. But it was the whispers in the day hall which served as the obiter dictum of Jennings’s death. It was like watching the unprepared attempt to start a fire, collectively contributing obscure memories and unverifiable facts of Jennings’s life. They threw anything on top of the cold embers that might help burn away the man’s anonymity.

“Who?”

“Jennings.”

“Who’s that?”

“The old man.”

“The one that cleans the office?”

“No, that’s Bill. The other one.”

“Lived with Rourke?”

“Yeah.”

“Didn’t he work at the furniture shop?”

“Metal products, I think.”

“Ran AutoCAD?”

“Something with computers.”

“I heard his family was killed in a car accident a few years ago.”

“Wasn’t he going home soon?”

“First of the year.”

There was callousness too. Jokes about his crime, or crimes.

“What did the pedophile say when. .”

Laughter at a funeral is a forbidden release of fear. And it was fear we’d been so successful at avoiding until Jennings died. Not because we cared for him, but because we failed to remember him. And in doing so, he reminded us of how easy it is to lose everything, only to die before being given the chance to get a fraction of it back. So we hated him for it, and the laughter and the anger allowed us to momentarily hold our ground against death. Death, who’d moved into Jennings’s cell and refused to be intimidated. Then the guards came back to pack out his belongings.

Attention in the facility:

cell house 1, first pull, west side dining hall,

cell house 7, first pull, east side dining hall,

seventeen thirty.

We are told that we have it easier than our predecessors. We are the last pull to chow tonight, so I watch the guards collect Jennings’s possessions. They consult Rourke about ownership of small items like toothpaste, soap, and deodorant. Appliances, like Jennings’s coffee pot and television, are easily distinguishable because his name and number are etched into the plastic. But canteen ephemera like bagels, peanut butter, aspirin, and candy that is left outside a foot locker is subject to the honesty of the surviving cellmate. Books, coffee cups, and other personal belongings are summarized on Jennings’s property sheet — a list of what he had and was allowed to have. But it is nonspecific. Caring more about quantities than actualities. With it, a correctional officer can tell how many books you own, but not which books in the cell are yours. It’s so generic, except for name and number, you can hardly tell the difference between one inmate’s and another’s.

The guards aren’t gentle yet neither are they insensitive with the deceased’s belongings. As I watch the traces of Jennings’s existence disappear one by one into the stiff green duffel bag, I wonder about how easy I am presumed to have it. Canteen. Visits. Phone calls. Better medical care, if “better” means the clinic will subtract three dollars from my account to tell me they couldn’t find anything wrong and shove a handful of ibuprofen in my palms. We have our radios and electric razors, hot pots and alarm clocks. I heard a rumor we’ll be getting iPods or iPads in a few months, though not the actual Apple product, just something comparable in function, made in the Philippines, with a pathetic six-month warranty. I suppose that is inarguably this progress everyone speaks of. Progress toward a punishment devoid of cruelty and unusualness. Perhaps in a hundred years it will be impossible to distinguish between a life before and a life after prison walls.

I wonder where Jennings’s belongings will go. His stuff. His things. What happens to the mementos of a man no one knows? Will the guards pick through them? I can imagine some correctional officer’s home cluttered with the possessions of the dead. Maybe the unopened items get restocked in the canteen warehouse. Or do they throw it all in the dumpster before moving along to the “memorial service”? A few words by a chaplain who may not have ever set foot inside your facility. Then what? Interment? Cremation? Burial? Something bureaucratic, efficient, and cost effective, I’m sure.

They announce the next cell houses for chow. My belly growls and I confess to myself I would have no ethical dilemma eating a dead man’s food or watching his television until they came to claim it. Possession is such an absurd idea to me now, like the feeling of driving past a house you once lived in long ago. It is alien and familiar at the same time, and I doubt I will resume it when I am allowed to leave. That’s ironic in a way, because it’s an implicit requirement for parole — work, buy, consume, possess.

Attention in the facility:

night gym for cell houses 3 and 4,

library for cell house 7,

AA meeting in multipurpose room 1,

Catholic Bible study in classroom 6,

nineteen thirty.

In the library, I pick up a book I’ve had on hold for two months. The Bardo Todrol Chenmo; The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Only that is a mistranslation. Literally, it means The Great Liberation Through Hearing in the Bardo . A bardo isn’t one definitive moment, but rather an age or period of time that has its flourish, plateau, and decline. It is a progression of moments before, during, and after life leaves the body, but can refer to any physical or spiritual transition. Death is a bardo, not some exact instant you can point to and say, That is when he died . According to the book, one’s state of mind at the end of one bardo is crucial to one’s disposition in the next. This series of bardos is collectively called samsara , the cyclic existence of beings and becoming. From human to hungry ghosts, samsara is divided into six realms, each one a metaphor for our unstable states of mind — fear being one of the most detrimental to rebirth.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Prison Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Prison Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Prison Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.